84K, by Claire North

I thought that, because I had read the first two books in Claire North’s Songs of Penelope series, that I had a handle on what Claire North’s writing was like.

Ha ha ha.

Ha ha.

Yeah no, turns out. 84K has been on my TBR list for a long time, and I was killing time in the library recently when I saw it just sitting there. So, fate dictated that I must pick it up. And I started reading it, and … oh my.

This is completely different from Songs of Penelope, is the first thing to say. People who go from this to ancient mythological Greece must have their heads spin, because doing it in the reverse did so to me.

This is not-too-far future England; this is nightmarish capitalism, business and government together, with basically no difference between them, and the literal end-point of the idea of human resources. Justice is privatised beyond even what the USA currently does; every crime has a cost, determined by accountants based on the societal worth of the victim (she was trash) and the perpetrator (he has a very promising swimming career ahead of him). This is people refusing to see what has been done to their society, in their name, while they get some personal gain from it; and just occasionally someone saying Enough.

This was a hard book to read, mostly for the subject matter. It’s not entirely unrelenting but it’s pretty close. North is doing a lot here, and really, really wants you to think about what’s happening. I can imagine this being compared to The Handmaid’s Tale and other stories that project from current events, and take political horror to its grim logical conclusion. It’s a totalitarian society where most people don’t realise it; it’s business being far more important than humans; it’s the personal cost of defying a society where most members don’t see a problem. And those things just don’t feel that far away anymore.

It’s also occasionally hard to read from a structural point of view; again, Songs of Penelope did not prepare me for a non-linear narrative structure. There, it really wouldn’t have worked; here… well. North is a poet; she is a skilled weaver of stories; she layers meaning on meaning and idea on idea so that by the time the story brings you back to the starting point, you’ve got so much knowledge and awareness of what’s going on that you’re close to bursting.

This is a phenomenal book. It deserved all of the accolades. (I’m still glad I read Songs of Penelope first.)

Rosalind’s Siblings – anthology

I heard about this anthology c/ Bogi Takács, the editor, and the premise immediately grabbed me (also I trust Bogi’s sensibility). It can be bought here.

The premise here – as the subtitle says – is speculative fiction stories about scientists who are marginalised due to their gender or sex, in honour of Rosalind Franklin – a woman whose scientific discoveries were key to the unravelling of DNA, but who never received the recognition that Watson and Crick did in their own time.

In Takács’ introduction, they note that the stories don’t take a simplistic view of science; there are stories where science is generally a positive force, and stories where it’s not. There are a variety of different sciences presented, a variety of ways of doing science, and a variety of contexts as well. There’s also a range of characters, across gender and and sexuality and neurodiversity and experience and ethnicity and everything else. This reflects the authors themselves, who are also really diverse. The stories, too, vary in their speculative fiction-ness; near-future, far-future, magical realism, on Earth or in the solar system or far away. There are two ‘trans folk around Venus’ stories, as Takács rather amusedly notes – and they are placed one after the other! – but they’re so different that I’m not sure I would have clicked to that similarity without having been made aware of it from the introduction (stories by Tessa Fisher and Cameron Van Sant; they’re both a delight).

As with all anthologies, I didn’t love every single one of these stories – that would be too much to expect. But there were zero stories where I wondered why an editor would include it, and all of them fit the brief, so those are pretty good marks. DA Xieolin Spires’ “The Vanishing of Ultratatts” was wonderful and hinted at an enormous amount of worldbuilding behind the story. Leigh Harlen’s “Singing Goblin Songs” was a delight, “If Strange Things Happen Where She Is” (Premee Mohamed) has gut-wrenching timeliness (science in a time of war), and “To Keep the Way” (Phoebe Barton) utterly and appropriately chilling.

Below the Edge of Darkness, Edith Widder

I heard Edith Widder on Unexplainable – one of my very favourite podcasts, such that I went back and listened to the year’s worth of episodes that happened before I found them (c/ Gastropod, another of my very favourite podcasts). She talked about deciding to use red light rather than white light when exploring the mid ocean and how that was a new thing, when she suggested it, and I was both boggled and entranced. I love me a good deep-sea exploration story, so when I discovered that the library had her book, I grabbed it.

I realise that the subtitle is “a memoir of…” but I didn’t realise that this was actually a memoir – that is, there’s more about her personal life than I had expected. Which isn’t a problem, it simply surprised me. Pretty much everything she talks about from her personal life is tied to her professional life, so in that sense it is very much a memoir rather than an autobiography: we don’t learn everything about her childhood, just about the very dramatic events that led her to eventually study bioluminescence and marine biology.

(Yes, I was one of those children who thought being a marine biologist would be cool. Yes, I thought it would involve whales and dolphins rather than plankton. No, I don’t love boats that much.)

Widder has been a leading light (heh, heh) for many decades in studying bioluminescence, and in figuring out how to video critters in the mid ocean – the largest living space on the planet – without actually interfering with their natural behaviour. If you’re interested in giant squid, you may actually already know of her: she’s responsible for the first footage of one underwater. She discusses a lot more than that, of course – ups and downs in research, things not going as planned, and generally learning really cool stuff about the place we know the least about on our planet. It’s nearly a cliche that we have better maps of the back side of the moon than of the depths of the ocean… but it’s true.

This book is awesome. The one thing I will say is that she does occasionally go on environmental tangents that feel disconnected from the rest of the chapter. Don’t get me wrong, she’s absolutely right and the book is absolutely the right place to be making the points (because I know she says it elsewhere as well). It just didn’t flow as seamlessly as it might have, which was a bit jarring overall. Nonetheless, it is generally really well written, and Widder has a brilliant sense of humour which often comes out in her footnotes. My very favourite is in discussion of the comparison of eye size, when she gives metric measurements for a giant squid’s eyes (30cm), and then says that in “American units” that’s 1/5 Danny DeVito’s height.

Highly recommended for my fellow science nerds, and fans of ocean science in particular.

Tusks of Extinction, Ray Nayler

Read courtesy of NetGalley and the publisher, Tordotcom. It’s out in January 2024.

I had read and loved Nayler’s The Mountain in the Sea, so it was a no-brainer that I should want to read this novella. There are some similarities between the two, and a whole lot of differences.

Most importantly, it’s fantastic.

I hadn’t read the blurb before diving in – why would I, when I had high expectations? I assumed it was going to be about elephants, or maybe mammoths, and honestly that was enough. So yes, it’s about mammoths – although not quite as I expected. Nayler dives into the thorny questions around what it might mean, and require to bring mammoths back from extinction: in terms of science (although it’s not overly science-heavy; it’s only novella-length, after all), in terms of mammoths learning how to BE mammoths, and in terms of the human reaction as well. In particular, the focus is on poachers, beginning with elephant poachers and the people attempting to thwart them in various parts of Africa.

There’s a lot of humanity, there’s a lot of animal conservation, there’s a lot of scientific consideration. It’s provocative in the best way – no devil’s advocate crap, but raising important issues that don’t have simple answers. Well-written and engaging, this is a further evidence that Nayler is someone to keep watching out for.

Ares Express, by Ian McDonald

When I read Desolation Road I had no idea that I was reading a companion novel to Ares Express. Happily, it doesn’t matter what order you read them in – there’s no spoilers, and only one character in common… who is fairly central to the plot of both, but in ways that work separately for each novel.

Every time I read a new McDonald novel I’m reminded of just how awesome a creator he is. Here, the focus is a young woman born to a train family – they drive trains around Mars, and everything about the family is focused on the train. It’s a weird mix of a society, because it’s clearly technologically advanced – or at least, there are aspects of that, since they’re living on a terraformed planet and they have various tech things that don’t exist for us. At the same time, though, there are archaic aspects to the human side, including, sometimes, arranged marriage. Such is the future looming for Sweetness Octave Glorious-Honeybun Asiim 12th, and she is not having it. And so begins an adventure across Mars that will eventually have enormous repercussions.

The way McDonald gradually reveals his vision of this future world is masterful. There’s enough, early on, to understand the basics of society… and then slowly, slowly, enough of the history of the place is revealed that the reader’s vision is broadened. It’s looking through a keyhole vs eventually looking through a door. But not stepping through that door – there are still lots of tantalising bits that aren’t fully explained, which just makes it all the richer.

Sweetness is a great focal character: young, impetuous, smart, unafraid of challenges and usually willing to admit when she needs help. I would have been happy with an entire novel focused on her. But McDonald adds Grandmother Taal, and I love her to bits. Old ladies being feisty, taking up the slack when the younger generation is being a bit useless, fearless and clever and willing to meddle: she’s everything I love.

One of the great things about writing a middle-future novel where there’s been some loss of tech for whatever reason is that, despite being over 20 years old now, it still gets to feel vital and believable and not at all outdated. Ares Express is magnificent.

Someone in Time (anthology)

I am late to the party… however, not SO late, because this just won the British Fantasy Award! Which it absolutely deserves.

I’m sure there are some readers who would avoid this because “they don’t read romance” (hi, I used to be one of those). The reality though is that you do; there’s almost no story – written or visual – that doesn’t include romance somewhere in its plot. What I have learned about myself is that I rarely enjoy what I think of as “straight romance” – that is, stories where the romance is the be-all of the plot; they just don’t work for me, as a rule. What I love, though, is when the romance is absolutely integral to the story and there’s a really fascinating plot around it. Every single one of these stories does that.

As the name suggests, this is set of stories involving romance and some sort of time travel. It’s a rich vein to mine, and every single one of these stories is completely different. Sometimes the time travelling is deliberate, sometimes not; sometimes the ending is happy, other times not; some are straight, some are queer; some pay little real heed to potentially disrupting the historical status quo; some have easy time travel while others do so accidentally; sometimes the time travel happens to save the world, and sometimes it’s about saving a single person. Sarah Gailey, Rowan Coleman, Margo Lanagan, Carrie Vaughn and Ellen Klages (a reprint) wrote my favourite stories.

And then there’s Catherynne M Valente’s piece. I did love every single story in this anthology; Valente’s story is breathtakingly different in its approach to both structure – eschewing linearity – and theme: the romance is between a human woman and the embodied space/time continuum. Hence the lack of linearity. It’s a poignant romance and sometimes painful romance; it also confronts the bitterness of dreams lost, the confusion of family relationships, the beauty of everyday life, and the ways in which even ordinary people don’t really live life in a straight line, given the ways our memories work (Proust, madeleines, etc). This is a story that will stay with me for a long, long time.

Herc – a novel

Read courtesy of NetGalley. It’s out at the end of August.

I am bored by Hercules as a hero. But as a character in other people’s lives – as a messy, complicated, often unheroic, flawed, and realistic person – I am THERE.

The man named Heracles by his parents (who then changes his name to Hercules (which is a cute way of getting around the Greek/Roman thing) because reasons) never speaks to the reader in Herc. Instead, it’s all the people around him who tell his – and their own – story, from birth to death: father, brother, sister, nephew, cousins; wives; lovers (male and female); cousins; others met along the way. This variety showcases the different ways that people interact with the man. Some love him, while others hate him. Some continually forgive his flaws, while others are unable to.

Hercules rarely comes across well. He is strong – but he has little idea how to mitigate that strength around ordinary people, and even seems unaware of what he’s capable of. He is aware of the terrible crimes he has committed – killing his music teacher as a child, murdering his first wife, Megara, and all their children, amongst other things – and accepts that there needs to be consequences… and yet. And yet he is still seen as a hero, by those outside of his immediate circle, and indeed often by himself. And yet he seems to largely get away with being terrible. And the book does not forgive him for that.

This story dives deep into the consequences of Hercules’ actions for those around him and it is pointed, it is complex, and it is deeply thoughtful. I would read more in this style any day of the week.

Divinity 36, Gail Carriger

Sooo I missed this when it first came out – but it turns out I’m not too far behind the times as I read this first one (in a day…), went to look for the second one, and turns out it came out the next day (which is today, as I write). And the third comes out in October, so actually I’m doing just fine.

If you just want to buy it, or read what Carriger has to say: https://gailcarriger.com/books/d36/

So there’s many different aliens, pretty much all interacting companionably. One particular species, the Dyesi, search the galaxy for sentients who can sing or dance and then put them through rigourous training and bring them together as pantheons, because at that point those artists are gods. Yes, it’s a bit “The Voice” – or, more accurately, “Idol” where the prize is to ACTUALLY be an idol. And their performances get broadcast across the galaxy, and people literally identify as worshippers and send in votives and so on.

The focus of this series is a refugee who has a lot of trouble with ordinary emotional interactions thanks to childhood trauma. Brought together with new people and compelled to live and work with them, this is inherently a story about found family and in that it is simply lovely. There’s also, of course, music and art, and – amusingly – food and cooking.

This is a very cosy story, as should be no surprise to readers of Carriger’s work: that is, there is real and important trauma in various backgrounds but (so far) little immediate or overwhelming danger to our heroes; there’s a lot of focus on friendship and figuring out how all of that works, with a sense that obstacles can and will be overcome (not in a cheesy way). It’s a generally upbeat, inclusive, humorous, joyful story – and honestly who doesn’t need that in their lives sometimes? If you haven’t read any Carriger but you loved Legends and Lattes, I suspect this will work for you.

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

I don’t think I’ve read The Island of Dr Moreau – or if I have, back when I thought I should read some classic SF, it was so long ago that I have no memory of it. I know the basic idea of the story: an island, where Dr Moreau has been doing human/animal hybrid experiments; I think things go badly? That’s it. I assume Moreau has a daughter in that story, but honestly maybe Moreno-Garcia just added her in? I don’t know, and actually I don’t care. I’m sure that for Wells aficionados there are lots of clever little moments in this novel. I didn’t see them, and it didn’t make a lick of difference. This story is fantastic in and of itself.

It’s set between 1871 and 1877, in what is today Mexico – specifically, Yucatán, which (I have learned) has sometimes been regarded basically as an island due to both geography and history. The story is told from alternating points of view. One is that of Carlota, the titular daughter, a young adolescent at the opening of the story. The other is Montgomery Laughton, an Englishman.

Carlota has grown up at Yaxaktun, a remote ranch, where her father has been undertaking experiments in creating human/animal hybrids. He doesn’t own it; he has been supported by Hernando Lizalde, who is expecting to get pliant workers out of the deal. Her mother is unknown, and her companions have been the hybrids themselves, along with the housekeeper Ramona. She hasn’t particularly wanted to leave, and has had a fairly good if spotty education courtesy of her father.

Montgomery has been away from England for many decades, and has spent several years now vacillating between intermittent work and considering drinking himself to death. He arrives at Yaxaktun to be the new mayordomo, although whether he’s meant to be more loyal to Moreau or Lizalde is unclear. His tragic backstory is gradually laid out although it’s never played up enough to really make him the focus of the story; for all that he shares narrator duties, Carlota is absolutely the centre of this book.

As you might expect, things do not go as Dr Moreau would like. His experiments do not produce the results he desires – and whether that’s perfecting human/animal hybrids for themselves, or somehow finding ‘cures’ to human problems, is debatable. Lizalde gets impatient at the lack of results, and brings the threat of shutting Moreau down. And then there’s Lizalde’s son, who visits and meets the lovely (and unworldly) Carlota, which has obvious consequences.

Along with the main narrative is the real-world historical situation that Moreno-Garcia sets the novel against. It’s a time when the descendants of Spanish colonists are figuring out their place in this world, when the question of who will rule and what the country will look like is pressing. It’s also of course a time of deeply consequential racism – towards the ‘Indians’, the native Mayans, as well as the not-officially-enslaved Black and other non-white people who live in the area. All of this informs how people interact, depending on how they ‘look’.

Moreno-Garcia writes a wonderful novel. The characters are vital and vibrant, the story is well paced, and the historical context makes it even more nuanced and interesting.

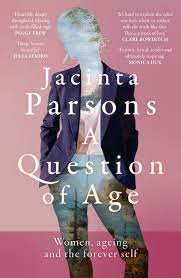

A Question of Age, Jacinta Parsons

Not the sort of book I would gravitate towards; but I heard Parsons speak at the Clunes Booktown festival this year, on a panel about ageing – which was interesting itself – and I decided it would be worth reading.

This is in no sense a self-help book, as Parsons says in the very first sentence. It’s part-memoir, in that it includes a lot about Parsons’ reflections on her own life and experiences – growing up, living as a white, disabled, woman, conversations she’s had with women about the idea of age and ageing; partly it’s philosophical reflections on the whole concept of ageing, particularly for women; and it also bring together research about what age means in medical and social contexts, the consequences of being seen as ‘old’, what menopause is and means, and many of the other issues around ageing. I should note here that it’s not just ‘life after 50’ (or 60, or 70); there’s also exploration of the experience of little girls growing up, the changes from adolescence into adulthood, and then into ‘middle age’ and ‘being older’.

It’s a book that’s likely to make many readers feel pretty angry. Not at what Parsons is suggesting (in my view), but the facts that she lays bare. About the way that girls are treated as they mature; about the way ‘old’ women are treated; at the way ‘old’ bodies are viewed, and everything around those moments. It made me realise how privileged I have been, in either not particularly experiencing (or not noticing) a lot of the sexualisation that women experience, and in not having a career that’s geared in any way around my appearance. I had a discussion recently with someone who mentioned that they didn’t feel like they were allowed to let their hair go grey, as I am – that their appearance was too important in their (corporate) work, and grey wouldn’t fit the image. I felt so, so sad that that’s what the world is enforcing. (I have always delighted in my grey streaks; it’s only partly because I am too lazy to bother with colouring it.)

Parsons is at pains to discuss what her identity means in the context of ageing – being white, and being disabled, being cis; she strives to include the experiences of queer, trans, and especially Indigenous Australian women throughout. It’s not even 300 pages in length so clearly it’s not the definitive book on the topic: a book with the same origin written by an Indigenous woman, or a collective, is going to turn out very different. Parsons is making no claim to be all-encompassing and I liked that. This is a deeply personal book, while also including a lot of science and stats and other women’s voices.

In many ways this feels like the start of a conversation. To use a meta book analogy, this isn’t the prologue – we’ve been having these conversations and there’s been research done in some important areas – but it’s around chapter 1 or 2. There’s still so much more to explore, and to examine, around ideas of ageing. And individuals need to be having these conversations, too – older women with younger, as well as peers.

Very glad I picked this up.