The Bright Sword

You could say that I’m an Arthuriana tragic, but I would snootily say that I am a discerning Arthuriana tragic. I will not read/watch just every version of Camelot that comes along, these days; I got that out of my system a long time ago. These days what I’m after is something that does Arthuriana differently, cleverly, and/or insightfully. And preferably does it with a knowledge of the enormous weight of history that it carries. Which is why Lavie Tidhar’s By Force Alone knocked me over; Tidhar faces not only TH White and Malory but also the very earliest Celtic stuff, and includes some super deep cuts that made me intensely happy (why yes, I did do a semester-long subject about King Arthur as part of my undergrad).

Lev Grossman was a guest at the Melbourne Writers’ Festival this year. I actually had no idea this book existed until I saw it in the programme, so of course I went along to hear what he had to say. He and CS Pacat had a very engaging and lively conversation, which led to me buying the book right after. One of the most interesting things Grossman said is that he thinks the whole Arthur story can be re-imagined for each generation to basically reflect current issues and ideas. So from this perspective White, in the aftermath of WW2, is writing about the impact of violence on society. Grossman sees himself writing around the idea of what it means to be part of a people, a nation, and how that works. He also deliberately set out to write a gender and sexuality-inclusive narrative. (Which is great, but I sat there wondering whether he or Pacat had read the Tidhar…).

The most intriguing thing about The Bright Sword is when it’s set, which is in the weeks after Arthur has been struck down, as have most of the knights of the Round Table. A new, bright-eyed young knight arrives at Camelot to find in disarray and the remaining knights utterly disillusioned. The story goes from there: what happens next? Woven around that is the backstory of those knights who are left, as well as Nimue, and their reflections on Arthur and Guinevere and Merlin and “England” and everything that happened with Camelot.

This was not a saintly, perfect, Camelot – although not as rugged as Tidhar’s. It’s good to see the problem of Uther’s rape of Ygraine properly acknowledged, for example. It touches on the Christianity/old religion issue, and some of the other things that have come up in Arthur reworkings over the last several decades. And because of where the story starts – with Arthur already gone – the end of the story feels genuinely innovative and unexpected.

This is a worthy entry into the Arthuriana landscape. Centring Sir Palomides, the Saracen knight, and Sir Bedievere, let alone Sir Dagonet or Sir Dinadan or Sir Constantine – these make for a fascinating story, and one that points out that side characters can be real characters. I have to confess, though, that I still think Tidhar’s book is a more challenging and clever one.

Francis of Assisi

I came to this book because I am friends with the translator. This does not guarantee that I was going to love it.

I am not Catholic. I have zero fascination with the idea of ‘saints’ in and of themselves; my primary interest is in how the women and men who get that title existed in their world. I also tend to have more interest in those who were regarded in some way as odd or outsiders in their time, or who lived in interesting places and times. So Francis is interesting, and also has the added dimension of being amongst the most well-known of all the Catholic saints. So I was fascinated to learn about this book being translated from the German. Having read it, I’m very glad it has been.

I was particularly fascinated by the book as an historian because Leppin spends a great deal of time reflecting on the primary sources available about Francis’ life: both the paucity of sources in general, and the intensely problematic nature of what does exist. Because Francis was canonised so quickly, and because his order already existed when he died – there are so many reasons to want to portray Francis in very particular ways, and reading through/around those to get to a ‘real’ Francis is always going to be challenging. So I deeply appreciated Leppin’s honesty around that, and his acknowledgement that ‘the truth’ is always going to be a challenge.

Nonetheless, I think Leppin does a good job of excavating Francis’ life, and presenting what we can reasonably understand about the man. I appreciated that Leppin isn’t interested in yet more hagiography, but in actually understanding a person – who wasn’t perfect, and made some odd choices, and whose heart we can’t fully understand, but who was nonetheless making some radical choices for his time.

And of course I need to mention the translation: and as with the best translations, you wouldn’t know that this is translated. It just… reads like a book. I can only imagine just how much work went into choosing the right words to both capture Leppin’s meaning and make the book itself work.

So, for those interested in Francis as a human, and how the Catholic church worked in the 13th century, this is a great book.

The Tainted Cup & A Drop of Corruption

I have not read much Arthur Conan Doyle. I’m pretty sure I read Hound of the Baskervilles when I was a teen, and maybe A Study in Scarlet? But I’ve never been an aficionado.

Which makes it all the stranger that I have consumed a lot of Holmes adaptations. The Downey Jr films; the Cumberbatch show; Enola Holmes, The Irregulars, and even the not-very-good Holmes & Daughter. And then there’s the books. I have read many of the Laurie R King Mary Russell & Sherlock Holmes books; I pine for the next in Malka Older’s Mossa & Pleiti series. Which brings me to Robert Jackson Bennett.

I had not heard of these books until the Hugo packet this year. And when I started The Tainted Cup I was a bit dubious, because I really haven’t been in the mood for gung-ho fantasy complete with made-up words for quite a while. But I persisted, because the characters were intriguing enough that I wanted to see what they were up to. And then the world grew on me – an empire shoring itself up against incursions from mindless oceanic leviathans (one assumes? I can’t tell whether that is going to get undercut later in the series), and one key way they do that is by changing some of its citizens: to have better reflexes, or more acute senses, or… other things.

And it didn’t take long for me to realise that Din and Ana are Watson and Holmes analogues. He is new to the justice job, struggling to find his place. She is weird, with bursts of manic energy and a delight in music and a desire of illegal drugs and an astonishing ability to put clues together. I mean, it’s not exactly subtle. And it’s an absolute delight. And you don’t need to know about Holmes and Watson to enjoy their interplay – it’s just an added amusement – because Bennett writes compelling characters and intriguing mysteries, and develops a world that stands by itself.

In fact I enjoyed The Tainted Cup enough that then I went and found A Drop of Corruption at the library, and I read it in a day and I have no regrets about that. Interestingly, the library has catalogued it as a mystery – I can only imagine what someone would think if they picked it up expecting something like Thursday Murder Club or a James Patterson. Anyway, it’s another gripping mystery in another part of the empire, and we learn more about how the empire works (and it’s not completely a “we love empire” story, either), and – happily – we finally learn a bit more about Ana, whose role and being are themselves mysterious. I assume Bennett has plans for more Din and Ana; certainly I will continue to read them.

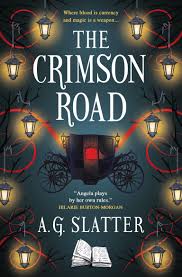

The Crimson Road, A. G Slatter

A.G Slatter is an author that I pretty much insta-buy these days. Especially when I know that the story is in her Sourdough universe. Even when the story is about vampires, which I am usually suspicious of – I do not love horror, as a rule; but I trusted that Slatter would not make the story too scary, and that those bits that make it horror would be worth me persevering through.

All of which was true of this novel. It’s yet another fantastic story. Which is not to suggest that I am getting complacent! I guess there’s a possibility that at some point Slatter’s imagination could go off the boil? Today is not that day, though, and may it be kept far, far away.

So: Slatter’s vampires are Leech Lords, and they have bee largely contained by an uneasy alliance of church and Briar Witches (whose story came out a year or two ago). It will not surprise you to learn that this containment is under threat.

Our point of view is Violet; we begin the story with her father having died, and she is hoping that she might now finally be free of his relentless tyranny and insistence that she train as fighter all day every day. Again, no surprise to learn that life is not actually going to turn into eating-chocolates-on-the-chaise-longe, although how all of that transpires is a wonderfully involved and intricate and devastating series of events.

That pretty much sums up the whole novel, really. There’s a quest; there are friends made and abandoned and fretted over; there’s fighting and surprises and hard choices.

I read this novel very, very fast because putting it down was anguish. Highly rated for anyone who wants more Sourdough universe; and if you haven’t read any Slatter yet, this would make an excellent entry point.

The Ministry of Time

What is there to say that hasn’t already? I read this because it’s on the Hugo shortlist this year, so that was already (likely to be) a good sign.

- Time travel done quite cleverly – excellent.

- Super slow-burn romance that basically makes sense – very nice.

- Politics that develop and get more and more tricksy as the novel progresses, in ways that I actually didn’t expect and was deeply impressed by as the book went on – magnificent.

- Pointed, thoughtful, and clever commentary about race, ethnicity, passing, immigration, assimilation – very, very nicely done.

This was another book that I had deliberately not read anything about before going in – the name told me all I needed to know, especially once it got on the Hugos list and friends started raving about having enjoyed it. So I went in with no expectations. (If you want to be like me, just stop reading now!)

I really didn’t expect that the idea was that people were being brought into the 21st century. I think the initial explanation of that is perhaps the weakest part of the story: why do this? I don’t think the “for science!” explanation is pushed enough to be convincing. And yes maybe that’s part of the point, but… on reflection, I do think that’s the one bit that’s too vague.

I really, really didn’t expect the whole explorers-lost-in-the-frozen-wilds chapters. They make a lot of sense in terms of elaborating Graham’s character. And it’s only in hindsight that I can see that they’re also doing some interesting work in terms of showing two groups, coming into contact, who find one another unintelligible.

One of the twists I picked up early – I think at the point where the author was starting to really flag it, so I won’t take any credit for being particularly clever. I did not pick up one of the other twists until it was presented to me, which was a highly enjoyable experience.

This is a debut, so I am left with “I hope Bradley has a lot more ideas left in her head.”

The Incandescent, Emily Tesh

I had absolutely no idea what this book was about before I started reading it. I had pre-ordered it months ago purely on the basis of “Emily Tesh”. That’s how much I loved Some Desperate Glory: Tesh has become an insta-buy.

So then I discovered that it’s a school story, with the focus on one of the teachers; and that it’s modern, and a fantasy. Very different from Some Desperate Glory! Which is not a problem – but intriguing.

TL;DR I adored this book. Like, a lot.

The school bit: I was a teacher for a fair while. Not in a private school, not in a private boarding school, and not in a British private boarding school. And yet, this book was so clearly written by someone who was a teacher. The notes about no one getting on the wrong side of the office staff. About respecting the groundskeepers. About how experienced teachers view new teachers, and why teachers even do the job… and that’s all before the actual teaching, and the teacher-student interactions. I loved it. And it’s all necessary and appropriate for the story, too.

The fantasy side: this is a world where magic-users can access the demonic plane and make use of their power to do… well, magic. There’s also other ways of doing magic but that’s the focus here. The main character teaches invocation, and is an acknowledged expert in her field. Some of her students are remarkably strong and intuitive. You can probably start to anticipate some of the ways things might go wrong.

There’s also romance: it’s a significant thread throughout, although more along Han-Leia lines (important but not actually driving the narrative) than Wesley-Buttercup lines. It’s real and powerful and deeply believable.

Tesh writes beautifully, I wouldn’t change a thing, and I know that I’ll be re-reading this novel. And I’m sorry if you’ve got a lot on your plate, Emily, but please can you write more novels?

The Strange History of Samuel Pepys’s Diary

Many moons ago, I did an undergrad subject that I thought was part of the English department but was actually in Cultural Studies. It was about how “classics” get to be part of the canon – about how much there is to the construction of the canon, and that it’s not just organic. So we looked at the various versions of Hamlet, and Pound’s editing of “The Wasteland”, and James Joyce’s work at making Ulysses seem like a classic before it was even published. All of which was in my mind as I read this amazing, fantastic book.

I read this book courtesy of NetGalley and the publisher, Cambridge University Press. It’s out at the end of June, 2025.

What Loveman is doing is not just assessing and explaining the Diary, but also putting it in its historical context across the 350 years of its existence. How and why Pepys originally wrote it – and the fact that it is almost certainly not JUST a diary recording his uncensored thoughts, but consciously constructed. And then, even more interesting for me, the life of the Diary after Pepys’ death.

The Restoration is not my favourite period, so I haven’t studied the Diary much, if at all – and being Australian, I wasn’t subjected to excerpts at school. So I had no idea that most of it is in shorthand, nor that for the last three centuries very few people have been able to actually read the Diary: what scholars have worked from is a transcription – a translation, even, given that transcribers don’t always know what was intended. And then there’s the fact that until the 1970s, there was NO unexpurgated version of the Diary published. Early editors cut out bits that were perceived as too raunchy, as well as bits that were perceived as too boring (also often, apparently, bits involving women…). So again, what people have “known” about Samuel Pepys has been constructed by choices, consciously or unconsciously made. The way Loveman sets out this publication history is completely absorbing in a way I hadn’t really expected.

This book is deeply historical: it’s thoroughly researched, involving I can’t imagine how much time in archives. It is simultaneously wonderfully engaging, clearly written, and inclusive of fascinating tidbits – a newspaper column written like Pepys during the First World War, making daily observations! And a biting section about the work of editors’ and transcribers’ wives, “With thanks to…”, for the enormous amount of unpaid work they have put in over the decades.

This is a book that appeal not just to folks who know something about Pepys and his diary, but to anyone with an interest in how history is constructed. Splendid.

The Baker’s Book

I received this book from the publisher, Murdoch Books, at no cost. It’s out now; RRP$45.

I am remiss in reviewing this book! My excuses are a) being away for a couple of weeks, and b) finding opportunities to bake things when there’s not many people around.

I am not particularly an aficionado of the Australian baking scene. In fact, I think there might be only one place mentioned in here that I know (more on that later). Thus I do not know whether this is a representative, or interesting, or eclectic set of bakers. I can guess that they are, based on recipes, but I don’t know for sure. What I can judge, though, are those recipes, and I can say: it’s a fascinating selection. There are easy things and quite hard things; ingredients I’ve never used, and equipment I won’t bother owning, and takes on old favourites. There are savoury recipes but mostly sweet, and recipes for different occasions. There are also personal reflections from the bakers: about their personal journeys, or perceptions of baking, and often how those things relate to life in general. It’s a really nicely constructed book, both in contents and in physical appearance.

Recipes I have made:

Continue reading →Bean there, Done that: The Martian (2015)

I adore this film. Unlike most of the other Bean films, I can’t count how many times I’ve seen it. In fact, I saw it twice at the cinema, and there’s not many films that I can say that about.

Side note: I read the Andy Weir novel because I loved the film so much, and all I can say is that whoever read that novel and had the vision for the film to be as good as it is was a genius. The book is bad.

- I adore the opening of this film. I love the set up – of Mars, of the astronauts and their relationships, and the fact that Watney is left behind almost immediately.

- I could commentate the entire film, but that would be boring and not the point of this post.

- (Chiwetel Ejiofor!)

- (The use of the video diary format is inspired.)

- And Sean Bean arrives! In a meeting where they’re discussing what on (Mars) Watney is doing with the rover. Hello, Flight Director Mitch.

- It’s a very boring business suit. What is WITH that vest.

- And a boring corporate haircut.

- And he’s already in conflict with the boss, because he wants to tell the Ares crew and the boss doesn’t.

- (Benedict Wong!)

- (I adore Benedict Wong.)

- Bean doesn’t often get to genuinely laugh in the films I’ve seen. His giggling reaction to Watney’s profanity is adorable.

- Never before have I basically wept for potatoes.

- That brown corduroy jacket, Bean, my goodness. I have no words.

- It’s Bean that questions whether they should cancel the inspections on the probe…

- and then of course he gets to be the Flight Director when the resupply probe launches.

- and is second to find out about “shimmy.”

- (Donald Glover!)

- I remain firmly convinced that Sean Bean was cast in this movie solely because of the “Council of Elrond” bit, and because he’s the one to explain to the poor media person what the phrase means.

- No one will ever convince me otherwise.

- Ever.

- I find it interesting to see the clash between the NASA Director and the Flight Director – Daniels and Bean – about whether the Ares crew should be told about the possibility of going back to get Watney.

- Bean is playing a disgruntled corporate dude, rather than a villain, which is a rather different role for him.

- Bean’s disingenuous “it wasn’t meeee” is (deliberately) completely unbelievable.

- That ARGYLE VEST is wild.

- This may be Bean’s least fashionably-dressed role ever.

- I love the whole Bean/Wong/Ejiofor scene about turning the MAV into a convertible for Watney’s ascent. Gives us one of the great lines of the movies (“I am excited about the opportunities that affords.”)

- (Beck going hand over hand around the outside of the Hermes with no tether is honestly the bit that makes me feel most anxious in the entire film.)

Verdict: a man stuck in a corporate world where he feels very torn between loyalties and ultimately goes with his gut feeling. Probably makes the right decisions for Watney, definitely the wrong decisions for his career. But hey, at least he doesn’t die, and gets to go play golf afterwards instead.

Movies: 6. Beans dead: 4.