Of Noble Family

Spoilers for the previous four books, I guess (first, second, third, fourth).

Things I love about this series:

It’s about married people being in love, even after being married for a few years. They even still have sex. With each other. Willingly.

It’s about married people having issues and problems – with one another and with the world – and, in general, working them out together.

The magic is really delightful and intriguing.

Kowal confronts relevant issues of the time in both a 19th century and a 21st century way.

Jane is just so AWESOME.

In this, the final (sigh) novel of the Glamourist Histories, Vincent is forced once again to confront his family background, and come to terms with it more than previously. He does so in Antigua, whence his father had fled some time ago… to his sugar cane plantation, and thus his slaves. Vincent and Jane travel to Antigua, and Kowal tackles the delicate and problematic issue of how to talk about slaves and slavery in an acceptable, humane, and true-to-19th-and-21st-century ideas way. Overall, I think she manages ell.

In this, the final (sigh) novel of the Glamourist Histories, Vincent is forced once again to confront his family background, and come to terms with it more than previously. He does so in Antigua, whence his father had fled some time ago… to his sugar cane plantation, and thus his slaves. Vincent and Jane travel to Antigua, and Kowal tackles the delicate and problematic issue of how to talk about slaves and slavery in an acceptable, humane, and true-to-19th-and-21st-century ideas way. Overall, I think she manages ell.

Jane was fairly well developed in the first book, as the main point of view character. She has changed and matured over the series, but it hasn’t been a surprising exploration of her character; our understanding has deepened, not changed. Vincent, however – his character has really been the focus, and continues to be in this book. And I think this makes sense, since it’s a lot about a woman learning about her beloved; a beloved who has for years been reserved for the sake of survival, discovering that love means he doesn’t have to be that way, thus learning about Jane what the reader already knows.

On the issue of slavery… I’m going to assume that Kowal did her homework; I’ve trusted her in other areas and it seems right to do so here. The one aspect I was… somewhat dubious, or afraid, of, was the language of the enslaved Africans. Happily for my state of mind, she speaks very clearly in her Afterword about the efforts she went to in order to get the dialects ‘right’, so that relieved me. As did the pointed discussion from some the Africans themselves that they were from different nations – that they spoke different languages, had different traditions with magic, and so on, no matter that white eyes might see them all the same. It made my heart sing.

Which brings me to the other bit that I really loved: the discussion of magic, and the differences in tradition between a European model and the different African traditions; that the words and ideas you use to try and explain magic will then actually impact on your use of magic. This was so cool!

It’s not all lovely; there are some distinctly distressing and unpleasant moments. But this is, at heart, a romance. And it’s comforting to know that this is the sort of romance where the characters do get to live together in harmony, despite and sometimes because of the difficulties they have endured.

And this time, I picked the Doctor. Not the first time he was mentioned, but I did find him. I am a little smug about that.

I’m so sad that this is the end, but I respect the author’s decision not to keep dragging Jane and Vincent through increasingly unlikely adventures just to keep mad readers like me entertained. And it’s not like I won’t be rereading the stories in future.

Slow Bullets

Alastair Reynolds is one of those authors that I basically preorder as soon as I hear something new is coming out. It’s fair to say that I haven’t loved the more recent stuff as much as the Revelation Space stories (something I am sure authors just loathe hearing), but I still read it and (generally… Terminal World didn’t work for me overall) enjoy it.

Slow Bullets is a stand-alone novella about war and renewal, peace and struggle, time and identity and sheer bloody-minded determination.

Slow Bullets is a stand-alone novella about war and renewal, peace and struggle, time and identity and sheer bloody-minded determination.

Scur is a soldier, although she wasn’t meant to be. Peace has been brokered but when your war spans multiple solar systems, it’s hard to get the message out. Scur ends up in stasis… and when she wakes up, something is deeply, deeply wrong. For a start she’s told that most of the others on the ship are war criminals; for another, the planet out the window doesn’t look familiar. And the nav beacons, that are meant to help with interstellar flight, appear to be on the blink….

There’s a lot going on here, and I can’t help but feel it might have been better served either as a novel or a short story (maybe novelette). With the latter, you could cut out some of the side-plots and focus really tightly on Scur and her revenge-seeking (which I didn’t love partly because it got a bit lost with everything else going on, partly because I don’t love revenge stories). With a novel, there would of course be more scope to examine the reactions of different people to their predicament, and spend more time on the issues of reconciliation (the ship is populated with people from both sides of the war, and it’s unclear to all of them who is a war criminal and who is not) and rebuilding lives that must now be entirely re-thought (no one is going back to Kansas).

I really loved the idea that if your main database is being corrupted (accidentally but irredeemably), and you’ve got this enormous spaceship with blank walls all around you, there’s a really obvious way of recording your history and culture for posterity.

I didn’t adore it but I am happy to have read it.

Hugo Awards: the novellas

… and now we get a little controversial…

As mentioned previously, I decided to read all the Hugo nominations. Because.

The novellas: I am… more torn than I have been previously.

“Big Boys Don’t Cry,” Tom Kratman: an AI battle-ship type thing, who is gendered female because of her call sign, is nostalgic for the Good Old Days when she had real soldiers instead of drones (*cough* Leckie *cough*). She is especially nostalgic because she so liked to cook for them… ?!? I’m sure it’s meant to ‘humanise’ the AI, but STILL. Anyway. The rest of the novella is Maggie (the ship) reminiscing as she’s torn apart for scrap. Hard to keep timelines straight, harder still to care about the characters; not Hugo worthy.

“Flow,” Arlan Andrews: actually kinda clever; young man goes on a journey and dicovers that the world isn’t as he always assumed it was. Andrews has done a passable job of thinking through some of the issues of not knowing about the sun and moon (our hero lives under a perpetual cloud bank). But the story itself was nothing of interest, the attitude towards women was decades old, and I just couldn’t bring myself to care about any of the characters.

“One Bright Star to Guide Them,” John C Wright: I didn’t hate the premise (this is where I start getting controversial, FWIW). Yes it’s using CS Lewis and maybe some Susan Cooper; no it’s not especially original (there’s even a lion, for eye-rolling astonishment). It’s too long, and definitely drags in the middle. As a story, I don’t actually mind it. But is it worth a Hugo? Sometimes, pastiches or homages are. I don’t think this one lifts enough, or gets different and interesting enough, to fall into that category.

“Pale Realms of Shade,” John C Wright: again, I actually didn’t mind the premise (ooh, see me keep on being controversial!). Told from the perspective of a dead PI, it’s a ghost telling its own story about figuring out who done the deed and why. It’s a story of self-discovery and repentance – maybe a bit late when you’re dead, but oh well. I imagine that some readers got peeved at the religious aspects; this is not a problem for me. As with the previous story I found it quite passable… spoiled by this line: “There were no steeples in that future, no church bells, just thin, wailing cries from thin, ugly minarets.” Uh. No.

“The Plural of Helen of Troy,” John C Wright: ready for me to get actually controversial? I’m not sure about this one.

That’s right. I actually liked this story and would consider putting this on my ballot. But it was published by Castalia House, and that sound you just heard? That was my politics running smack bang into my reading enjoyment.

The story is told backwards; another PI, this time working in a city outside of time somehow – I’m generally quite capable of reading time travel stories without the paradoxes doing too much to my brain, as a rule, although I know that’s not possible for many readers. (What can I say, it’s a gift. Like reading Greg Egan science.) He’s contracted to help a man whose girlfriend (?) is apparently going to be attacked by someone, and they have to stop it. Of course things get messier than that, and there are iterations and variations as the story progresses (…which means going backwards…). There are some neat moments – I was quite amused by the realisation of who the man and the ‘Helen’ were, and some funny enough moments of these people completely out of their times living together. Including Queequeg. QUEEQUEG LIVES.

Anyway. Now I have to figure out how to vote in the novellas and it HURTS. I’ve got a couple of weeks, right? I can figure it out in that time…

Hugo Awards: the novelettes

As I said in the last post, I decided to read the Hugo-nominated fiction because I wanted to be able to comment on their merit, as well as the politics.

The novelettes: no, no, no, no and no. Again, nothing worthy of a Hugo nomination in my opinion.

“Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust, Earth to Alluvium,” Gray Rinehart: I kinda liked the concept, but the characters were nothing and there was no fleshing out of consequences either physical or metaphysical. Could probably (can’t believe I’m saying this) make an interesting novel if some effort was put in to the characters, especially.

“Championship B’Tok,” Edward M Lerner: a somewhat interesting premise although not at all original. Some military speak, some boring characterisation.

“The Day the World Turned Upside Down,” Thomas Olde Heuvelt: I feel like this definitely owes something to “The Water that falls on you from nowhere” – which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it did win a Hugo after all, but it doesn’t make itself different enough. I didn’t like the main character, which isn’t a problem necessarily, although I think we are meant to sympathise and I just couldn’t do that. Better than the other nominees buuuuut still not award material.

“The Journeyman: In the Stone House,” Michael F Flynn: did not finish. Excruciating to try and read, characters utterly unappealing.

“The Triple Sun: A Golden Age Tale,” Rajnar Vajra: plucky young things manage not to get themselves killed or thrown out of the service by being obnoxiously cleverer than people who’ve been on the ground for some length of time. Weird aliens are weird and not developed enough.

Galactic Suburbia 123

In which classics, what classics, we’ll pick our own canon thanks, and reading Heinlein becomes less and less compulsory every year, so try not to worry about it. Actually, no books are compulsory. Read what you want to read. Book-shaming is the worst. Don’t do that. You can get us at iTunes or at Galactic Suburbia.

Introducing The Wimmin Pamphlet: serving you a diverse range of feminist thought since this fortnight.

Strange Horizons essay by Renay – Communities: Weight of History

Renay, we are with you! Anti-Impostor-Syndrome Reading and Life Support Group Is Go!

James Nicoll’s reviews of Women of Wonder, the Pamela Sargent books Tansy refers to as her SF education, highly recommended: 1 & 2

What Culture Have we Consumed?

Alisa: The 100 Season 1; Tiptree Bio, Julie Phillips, Sens8

Tansy: Rocket Talk Ep 53 on Spec Fic 14 & online writing in the spec fic scene, Loki: Agent of Asgard; Fresh Romance #1

Alex: Hugo fiction reading: short stories, novelettes, novellas, novels. OMG the decisions! The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison, The Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu, Ancillary Sword by Ann Leckie.

Also New Horizons!!

Please send feedback to us at galacticsuburbia@gmail.com, follow us on Twitter at @galacticsuburbs, check out Galactic Suburbia Podcast on Facebook, support us at Patreon and don’t forget to leave a review on iTunes if you love us!

The Goblin Emperor

… There’s going to be more, right?

This is really not the sort of book I would have been likely to read immediately off my own bat. 15 years ago, perhaps, but I haven’t really read secondary world fantasy like this for ages… and not necessarily for a reason I can put my finger on, aside from I Like Spaceships More.

This is really not the sort of book I would have been likely to read immediately off my own bat. 15 years ago, perhaps, but I haven’t really read secondary world fantasy like this for ages… and not necessarily for a reason I can put my finger on, aside from I Like Spaceships More.

Still, it’s on the Hugo ballot in The Time Of Rabid Puppies, and a lot of people whose opinion I generally respect have raved about it, so I wasn’t too sad to be sitting down with it as part of my Read The Hugo Ballot binge.

And I really liked it.

This stills seems improbable to me. Lots of ‘thee’s and formal ‘you’s and so on – the sort of thing that sometimes makes me break my eyes in the rolling. It’s goblins and elves for… no reason I can see? The elves have non-human ears which you only know because they’re described as doing things like flattening when the person is annoyed, and goblins just seem to have darker skin and maybe grow bigger than elves? But goblins and elves do intermarry; Our Hero is a product of just such an (unhappy, arranged) alliance.

And it’s not like the book is startlingly original in its plot. Emperor and his sons all die together, leaving one nearly-forgotten son by aforementioned unhappy marriage to inherit the throne. There are political machinations, palace intrigues, quandaries over who to trust, questions over whether someone in such a position can have real friendships… y’know, the normal things that happen when an unlikely heir takes the throne. We’ve all been there.

And yet. And yet. It works. Much of this is down to Maia, Our Hero. He may be the forgotten heir but he’s not completely stupid; clueless at times but not a Garion figure; possessed of a brain and determination and a desire to do some things his own damn way, thank you very much. I’m reminded somewhat of the story I heard once about Queen Victoria: that when she was crowned (I think?), one of the first decisions she made was to sleep in her room by herself – without her mother – for the first time ever. Maia isn’t just led around by the nose. But neither is he super arrogant, thinking he can do anything he likes and deciding to do just that; nor is he super capable in an impossible period of time. Addison strikes a good balance of learning the ropes and being actually, like, capable.

I liked many of the other characters (Csevet for the win), and the variety of female characters is really nice. I like the honesty with which Addison confronts the issues of arranged marriages, and the different ways of thinking about things like duty and honour.

Basically, when I finished reading it (in one day), I wrote that opening sentence: there

is going to more, right?

Dungarees

Yes, I knitted some.

These were… epic. For me. One of the more involved projects I’ve undertaken, because the legs are all moss stitch. It wasn’t actually hard (although some of the instructions didn’t make that much sense), but – yeh. They took a while. Not sure I’ll make them again unless someone very, VERY dear to me has a toddler. And even then they better be pretty darn cute.

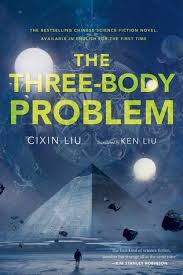

The Three-Body Problem

What on earth can I say? If I said “Liu Cixin is like a Chinese Greg Egan” that gives some idea of the complexity of the science… and I cannot imagine what it must have been like for Ken Liu to translate those sections.

The focus of the novel is split over a few characters and periods:

The focus of the novel is split over a few characters and periods:

Some of it is set in the Cultural Revolution of the 60s, and explores some of the consequences of this for academics in particular, via one woman and her family. I have taught this era (only once, but that’s better than naught), so I have no idea what the average reader would bring to this – and especially not what an average American reader would think. Ken Liu has done a good job of providing some footnotes with explanations, without (I thought) interrupting the flow of the narrative too much. A young woman, Ye, whose family was targeted ends up working at a mysterious scientific/military outpost…

Some is set in a ‘present’ that I don’t remember being identified, but is not one of William Gibson’s ‘tomorrows’ – it felt perfectly normal. Here, a scientist starts encountering weird things and gets drawn into an investigation that turns out to be even weirder than expected, and involves the whole world (there are scenes involving the Chinese military brass and NATO officers which had me shaking my head at the possible ramifications).

Some it is set in-game: the scientist, Wang, starts playing a game called Three-Body Problem – which it took me ages to realise is the conundrum of how to figure out the physics of three bodies interacting with each other gravitationally (it’s been a while since I thought physics, ok?). The game is connected to the investigation and also allows Liu to write THE most hilarious description of people physically being a computer ever, and this from someone whose knowledge of computational logic is non-existant (NAND and NOR gates? I admit my eyes glazed over somewhat…).

Some of it is set… elsewhere… not telling where.

I liked Ye a lot; the complexities of being first condemned, and then being considered useful but still politically unreliable, then rehabilitated into society – it’s done very nicely. I didn’t like Wang as much, which I think was mostly to do with his attitude towards his wife and son: basically he ignored them, and I found this quite unpleasant. Da Shi, a policeman involved in the investigation, is magnificent and is the character I would most like to see in a mini-series version of the book.

I had heard that some people thought there was a lot of emphasis on the Cultural Revolution, so I was surprised to find that for me, at least, it’s not actually a very big part of the story – page-wise anyway. It’s certainly of fundamental importance in Ye’s development, don’t get me wrong, but there’s definitely far more time spent in the present (and probably more time spent in-game by one of the characters, although I haven’t checked the page numbers to confirm that).

I am beyond impressed that this made it on to the Hugo ballot (yes yes after one of the Rabid nominees pulled out). I’m really glad it did, since it made me read it sooner than I otherwise would have. I really enjoyed it. There are some parts where, as with a Greg Egan novel, I skimmed over some science because I just can’t come at the physics anymore. But that wasn’t a problem with understanding the plot or the characters, and actually – especially considering this is a translation – much of the science-speak was quite accessible. (Ken Liu has an interesting discussion of the issues of translation at the end of the version I read, which was in the Hugo packet; it’s a very thoughtful essay about staying true to the vibe of the thing as well as/instead of staying true to the actual words and phrases used.) I discovered only when I got to the end that this is the first in a trilogy… I believe I may well be reading the rest.

But who am I going to put first on my Hugo ballot?!?

Beauty, by Sheri Tepper

Sheri Tepper looked at a map showing the boundaries of different genres and, taking a fine black marker, drew her own shape instead.

Fantasy: there’s magic and faeries and they’re a real part of the world.

Fantasy: there’s magic and faeries and they’re a real part of the world.

Science fiction: time travel and a dystopian future are integral to the plot.

Fairy tale retelling: the titular character is meant to be Sleeping Beauty (… and that phrase should be understood in a couple of different ways).

Horror: a couple of sections, for my tastes anyway.

Christian allegory: tied in with the Faery aspects, they work quite nicely.

Bildungsroman: the novel covers pretty much the entirety of Beauty’s life.

Environmental cry for help: the future is a horrible place unless we get on with changing things NOW.

Family drama: oh yes. Oh my yes.

I know there are other authors who do similar things, but it’s rare to find such a magnificent combination of elements that are traditionally ‘fantasy’ (faery, fairy tales, etc) with those that are science fiction (time travel in particular). I can absolutely see why Tepper is being honoured with the World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award, and this is the first of her books I’ve read (… I’m pretty sure…). There is just no question for her that of course a dystopia can coexist with the concept of magic, that fairy tales can be reworked together with time travel.

14th-century Beauty lives with maiden aunts and her father, when he’s not off crusading. Her mother died in childbirth, or so she’s been told, but when her father intends to marry again, she discovers that maybe things are weirder than expected. And then things get really weird when she encounters people from the future and she is whisked away with them, to a decidedly brutal and unpleasant future of billions of people, little room to move and less food. She doesn’t stay there, but ends up travelling… elsewhere…

Look, I can’t say too much else about this book because finding all the amazing twists and turns is an absolute joy. Tepper writes beautifully, at times grimly; she constructs a complex character in Beauty and surrounds her with genuinely varied friends and foes and family. SO MUCH happens in fewer than 500 pages. It’s magnificent.