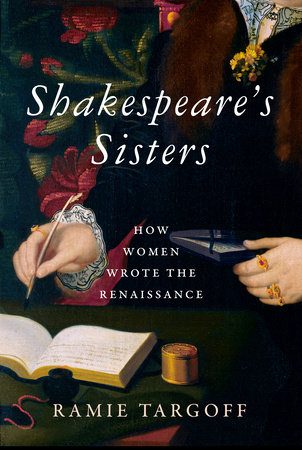

Shakespeare’s Sisters, Ramie Targoff

Read via NetGalley. It’s out now.

I’m here for pretty much any book that helps to prove Joanna Russ’ point that women have always written, and that society (men) have always tried to squash the memory of those women so that women don’t have a tradition to hold to. (See How to Suppress Women’s Writing.)

Mary Sidney, Aemilia Lanyer, Elizabeth Cary and Anne Clifford all overlapped for several decades in the late Elizabethan/ early Jacobean period in England – which, yes, means they also overlapped with Shakespeare. Hence the title, referencing Virginia Woolf’s warning that an imaginary sister of William’s, with equal talent, would have gone mad because she would not have been allowed to write. Targoff doesn’t claim it was always easy for these women to write – especially for Lanyer, the only non-aristocrat. What she does show, though, is the sheer determination of these women TO write. And they were often writing what would be classified as feminist work, too: biblical stories from a woman’s perspective, for instance. And they were also often getting themselves published – also a feminist, revolutionary move. A woman in public?? Horror!

Essentially this book is a short biography of each of the women, gneerally focusing on their education and then their writing – what they wrote, speculating on why they wrote, and how they managed to do so (finding the time, basically). There’s also an exploration of what happened to their work: some of it was published during their respective lifetimes; some of it was misattributed (another note connecting this to Russ: Mary Sidney’s work, in particular, was often attributed to her brother instead. Which is exactly one of the moves that Russ identifies in the suppression game). Some of it was lost and only came to light in the 20th century, or was only acknowledged as worthy then. Almost incidentally this is also a potted history of England in the time, because of who these women were – three of the four being aristocrats, one ending up the greatest heiress in England, and all having important family connections. You don’t need to know much about England in the period to understand what’s going on.

Targoff has written an excellent history here. There’s not TOO many names to keep track of; she has kept her sights firmly on the women as the centre of the narrative; she explains some otherwise confusing issues very neatly. Her style is a delight to read – very engaging and warm, she picks the interesting details to focus on, and basically I would not hesitate to pick up another book by her. This is an excellent introduction to four women whose work should play an important part in the history of English literature.