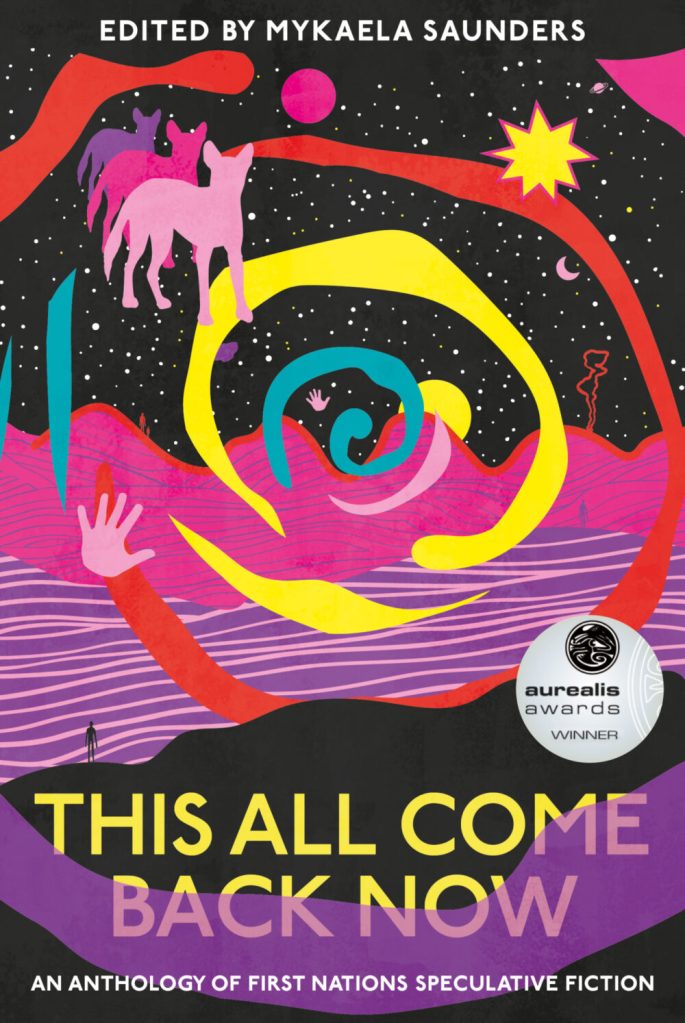

This All Come Back Now – anthology

This came out last year, and I only found out about it this year… oops; not sure how I missed it (especially given its Aurealis Award!). Available from UQP.

The first all-Indigenous Australian speculative fiction anthology! Exciting that it exists; disappointing that it took until 2022 for it to exist. Oh, Australia.

First, how glorious is that cover? It’s so vibrant and exciting.

The editor, Saunders, gives a really interesting intro to the anthology. I go back and forth on whether I read intros to anthologies; sometimes they seem like placeholders, and sometimes they give a wonderful insight into the process. This is the latter (although I did skip the last few pages, where Saunders discussed the stories themselves; I don’t like reading that until after I’ve read the stories myself. YMMV). The comparison of an anthology with a mixtape has given me all sorts of things to think about. There’s also a brief discussion of First Nations’ speculative fiction – that it exists despite what a cursory overview of the Australian scene might tell you – as well as that insight into the creative process. This is one introduction that was definitely worth reading.

The stories themselves are hugely varied; this is not a themed anthology, like Space Raccoons, but instead is tied together by the identity of the authors. That means there’s experimental narratives and straightforward linear ones; recognisably gothic, science fiction, and fantasy stories; and other stories that refuse to fit neatly into categories. As with all such anthologies, I didn’t love every story; I have limited tolerance for surrealism, as a rule – it just doesn’t work for me, but I know it does for others. Some of these stories, though, will sit with me for a long time. Karen Wyld’s “Clatter Tongue,” John Morrissey’s “Five Minutes,” Ellen van Neerven’s “Water,” just as examples – they’re profound and glorious.

I love that this anthology exists. I’m torn between hoping there can be more books like this – because featuring Indigenous perspectives and writing in a concentrated way is awesome, showcasing the variety of stories and voices – and hoping that the authors featured here will also be published in other anthologies, and magazines, and have their novels published, as well. Maybe that’s not a binary. Maybe we can have both. That would be nice.

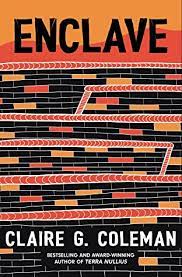

Enclave, by Claire G Coleman

I received this from the publisher, Hachette, at no cost.

If you’ve read Terra Nullius or The Old Lie, by Coleman, then I heartily recommend the same strategy as I used: just read the book. Don’t read this review, don’t read the blurb. You already have a sense of how Coleman writes, and what Coleman writes. The first two were very different, but you know how they’re similar; this is also very different, but it’s clearly a Coleman novel. If you were staggered by those first novels, then you really don’t need to anything else other than: it’s a new Coleman novel.

Still with me? Haven’t read either of the first two (but now you know you should because they’re amazing), or somehow not sure about this one? Christine lives in a walled city with no contact with the outside world. Everyone knows that the outside world is terrifying, full of violence and bad things; unlike their city, which is calm and peaceful and carefully surveilled for any trouble. Everyone who lives inside this city is white; the bussed-in servants are brown, but they’re nameless and just go about making houses liveable. Christine isn’t entirely happy – her best friend is missing and she doesn’t know what to do – and then does something unforgivable, and then everything changes.

It’s fantastic.

Living on Stolen Land

This book was sent to me to review by Magabala Books. It comes out in July – so very timely – and will be $22.99.

I am an Anglo Australian. My most recent migrant ancestor is maybe 4 or 5 generations back. I am a history teacher. And I live on stolen land. I benefit every day from the fact that indirectly each of my ancestors (and directly, in a couple of cases) contributed to the displacement of Indigenous Australians.

Ambelin Kwaymullina has produced what the media release calls a “prose-style manifesto”, and what I would describe as a free-verse lesson about the past and the present and the future. She’s also responsible for that gorgeous cover and the internal images that help make this a lovely object as well as a powerful text.

Kwaymullina covers so much stuff that I want everyone to experience that I’m tempted to re-hash everything she says… which would be, as she herself points out, a white woman re-interpreting an Indigenous woman and that’s exactly the sort of thing that really needs not to exist. (I’m also currently reading Aileen Moreton Robinson’s Talkin’ Up to the White Woman, so… yeh.) So let me say that she makes it very clear – in case there was any doubt in the reader’s mind – about the original ownership of this land we call Australia; about the ongoing problems of the way we settlers talk about the land and its original inhabitants; and also points ways forwards as to how all of the people now living here might actually make it work. For everyone. As the blurb says, this is a “beautifully articulated declaration… a must-read for anyone interested in decolonising Australia.”

There are two bits that particularly got to me. Firstly, as a history teacher, Kwaymullina’s discussion of time is breath-taking (pp12-14): her description of linear time, where “Things that happened / a hundred years ago / are further away / than things that happened yesterday” – and is “weaponised against Indigenous peoples” and gives “the illusion of progress / regardless of whether / anything has changed”. And it’s that last bit that took my breath away. Then she speaks of Indigenous systems where “time is not linear” – cycles, instead, and “as susceptible / to action and interaction / as any other life”. And then she points out that cyclical time is a gift and a responsibility because “The change has not been lost / for justice / for change” and I nearly cried. I have never thought of time like that and never realised that it was even possible that life could work like that.

Secondly, Kwaymullina has a very pointed section about “Behaviours” from Settlers, and the four different ways we might act. Those who speak well and do nothing, the Saviours, the ‘discoverers’ (appropriating Indigenous stuff for their own life… and the change-makers. And this section made me really think about the ways that I act, and have acted, and intend to act.

Look. This book is 64 pages of free verse that will gently and pointedly make you think about yourself and and your ways of thinking and your understanding of history and the possibilities of the future. I will read this book again and again, I will read it to my students, I will share it with other people, I will tell other people to read it. Every household should have a copy of this and I don’t use the word ‘should’ lightly.