Object Lessons: Ballot

You can take compulsory voting from my cold dead hands.

I read this book c/ NetGalley and the publisher, Bloomsbury. It’s out now.

I love every Object Lessons book. In some ways, this one is like the rest – part history, part social commentary (almost anthropology), part personal experience. However, it’s a much more immediately relevant topic than, say Skateboarding or Perfume. As well, all of those have been partisan – they’re written by people who like skateboarding and perfume – but it’s much more obvious in this one: the author is outspokenly progressive – votes Democrat, because America, although – happily – she is also very clear on the failures of various Democratic leaders.

Compulsory voting forever.

One important thing to note here is just how American this book is – more noticeably than many of the others I’ve read. The author is American, and it’s one of the most personal Object Lesson I’ve read, so the narrow focus flows from that. Which is not inherently a problem – American voting is a fascinating / appalling thing to view from afar. What is… let’s say disconcerting is the way the book is written without acknowledging that it is, functionally, entirely aimed at an American audience. Does anywhere else vote on its judges? The local equivalent of district attorneys or sheriffs? Maybe they do, but nonetheless – that shit’s wild. Plus all the state vs federal laws, not to mention the college system OMG. Thus much of what the author says is not automatically applicable to my experience, and I would guess not to the experience of many other people around the world. (This comment also reflects that I had not carefully read the blurb, so partly this is on me.)

I will fight for compulsory voting.

(Note: it’s actually not compulsory to vote. It’s compulsory to get enrolled; then it’s compulsory to choose between a fine ($100) or rocking up at the election and having your name marked off. No one compels you to mark a ballot and put it in the box.)

I knew some bits and pieces examined here. The whole voter ID thing, and how it’s manipulated – wild. (Doesn’t happen in Australia.) “Use it or lose it”?? See note re: compulsory voting. The ways in which prison populations – mostly filled with people who can’t vote – are still counted as population for purposes of figuring out county borders etc?? Everything about this system makes me, an Australian with a clearly perfect and incorruptible election system,* laugh at the idea of America as a wonderful democracy.

Another thing to note is that this is not a history of the physical ballot process, which I initially assumed it would be. The process (as it happens/ed in the USA) is covered super briefly. Instead, this is essentially an overview of voting practices in the very recent US past. Which is certainly interesting, if not what I thought I was getting (see previous comment about not having read the blurb, and that’s on me.)

It’s very well written, and completely depressing.

* This is a joke.

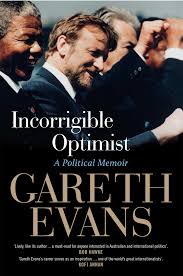

Incorrigible Optimist: Gareth Evans’ Political Memoir

Look. I’m a history teacher, and a cynic. I understand the point of a political memoir. So on the one hand, reading this was amusing because for all the self-deprecating humour and the admission of bad decisions and poor choices, it’s still an exercise in ego to write memoir.

And on the other hand: I just want more politicians to be like this. To be passionate about things that will actually make a positive difference. To be self-aware. To be willing to make hard, necessary decisions. I was a child of the 80s and 90s – at the back of my mind, “the Australian government” is Bob Hawke and Paul Keating and, yes, Gareth Evans.

I don’t read modern biographies, as a rule, and I really don’t read autobiographies. They hold zero fascination for me. I can probably remember every 20th century biography I’ve read: the Dirk Bogarde one my mother gave me (I went through a serious Bogarde phase), and Julie Phillips’ Alice Sheldon/James Tiptree Jr one; ones about Vida Goldstein and Emmeline Pankhurst; and one about Alexander Kerensky. Oh and Gertrude Bell! That’s literally the list – and given the number I’ve read about people who died before 1800 (and it’s only that late because of the French Revolution – oh Danton, you’ll always live in my heart), six is nothing. But now we can add this to the list, which I read for Reasons that may eventually become clear (not in this review).

This is, of course, not really an autobiography. It’s a political memoir – I think Evan mentions his wife twice? maybe doesn’t mention his kids at all? – so there’s no discussion, really, of anything outside of what has shaped his attitude to policies and ideas. It’s also not just focused on himself acting, but also on his ideas. There is an entire section where he’s outlining the pillars of the “responsibility to protect” concept that I had no idea about, but which he was fundamental in drawing up for the international community; sections where he talks about how universities (and especially chancellors) should function, why nuclear weapons should be utterly eliminated, the importance of international cooperation… this is not just a memoir: it’s a manifesto. Honestly, it’s a bit swoon-worthy.

Realise when this was published, though, and it feels like a dream of a half-forgotten world. Because it was mid-2017. Trump was just elected for the first time; Brexit was relatively new. Dreadful things had happened in Syria and Libya, and Russia was making its first forays around Ukraine. Scotty wasn’t even being joked about as PM. So when Evans discusses his hope that Trump might eventually “submit to adult supervision;” when he talks about his hope that “responsibility to protect” might be a real factor in international discussions when populations are at risk of war crimes and genocide… well. There’s a part of me that wishes I could go back to that time, and live it again, knowing how good it was.

This book probably doesn’t have that much appeal beyond Australia’s borders – unless you want to just read it for the foreign policy aspect, and for Evans’ involvement with Crisis Group and various UN and regional Asian events, all of which are quite fascinating. But if you’re like me – with a vague interest in Australian and international politics, and especially with a memory of those Labor glory days – this may well be of interest.

Infomocracy

Not sure how I missed this one when it came out a few years ago… some failure of mine or the system, I guess. Anyway, I finally read this (and the rest of the trilogy) last year, and felt a hankering need to reread this year. And apparently I didn’t review it last year, so now’s the time!

There’s no specified year that this book happens; it’s two decades after the near-global institution of micro-democracy, and it’s still a fairly recognisable world aside from that, so mid to late 21st century makes sense. Micro-democracy means that most of the world has been divided into ‘centenals’ – areas of 100,000 people (or is it voters? that’s unclear, I think) – and each centenal votes in their chosen government. The biggest are Heritage, which seems like an ordinary conservative party, and Liberty, which is theoretically all about citizen freedom… then there are some old-nation-based parties, like 1China; and most terrifyingly, there are military-based parties and corporate ones, the largest being PhilipMorris. In the long run I’m not sure which of the latter two are most scary. And then, the party that gets the most centenals over the whole world is the Supermajority and they get… some unspecified powers.

This entire book is about the lead-up to the third global election. I know, it doesn’t sound like it should be riveting. But oh my goodness, it is.

Firstly, this isn’t just a world with micro-democracy. It’s also a world with Information. Information is like Google, I guess, but made a public utility that is genuinely meant to be working for the good of everyone. There’s a touch of cyberpunk in that most everyone can access Information via a handheld device if they must, or via optical implants if they can; depending on your Information settings, you can walk around anywhere and get facts about the construction of buildings, names of plants – and the public Information of the people you’re around. Older begins to explore the consequences of Information here (and I know it’s ‘begins’ because that’s something that continues throughout the trilogy, SORRY SPOILERS). And what happens when Information isn’t available?

Secondly, of course something nefarious happens, and it needs to be rectified. The two focal characters are Mishima – absolutely my favourite – and Ken. Mishima works for Information doing a variety of things, which sometimes involve a stiletto and shuriken and climbing furniture. She also has a ‘narrative disorder’ which is never fully explained but helps (usually) to sort through a mass of data. Ken is a campaigner for one of the middle-tier parties, Policy1st, who ends up finding out some of the nefarious things and gets pulled into the action. Ken’s fine; he’s an interesting mix of altruistic and self-interested that makes sense, and his doubts and angst are portrayed sympathetically but not at annoying length. Mishima is awesome; she is splendidly capable but not all-knowing, and I basically love everything about the way she acts, reacts, and thinks.

This is seriously awesome book. I guess it’s on the ‘techno-thriller’ side of things although exactly what that means I’m a bit hazy on. I would be confident recommending this to someone who doesn’t love SF, because it could almost be tomorrow; the tech’s not that outrageous. It’s fast-paced but not ludicrously so, there are a range of characters who show a range of issues, and it’s just great.

On suppressing women’s writing

Just the front cover is enough to make me cranky. It’s a list of the ways in which women’s writing (and art) has been suppressed; the book is a brief and eclectic examination of how those different modes have operated, and some suggestion of why, too.

Just the front cover is enough to make me cranky. It’s a list of the ways in which women’s writing (and art) has been suppressed; the book is a brief and eclectic examination of how those different modes have operated, and some suggestion of why, too.

I finally got my hands on this book after I heard of Russ’ death. I’d heard of it in vague terms over many years, and more specifically in the last couple – particularly thanks to Galactic Suburbia, and a growing realisation that I really wanted to understand feminist SF, and that Russ is one entry into that. Plus, she seems like one of those writers everyone talks about… but few (especially of my generation, we post-70s women) have really read.

Russ progresses logically through various modes of suppression, dismissal, and marginalisation. As her evidence, she uses reviews of women’s work over the last century and a half or so; their presence (and absence) in anthologies and university curricula; and in biographies, as well as other sources.

The comparison of the different ways Charlotte Bronte’s work was received when it was believed to be by a man compared with when it was known to be by a woman were distressingly similar in some ways – given the difference in time – to the reception of James Tiptree Jr’s work as male/female. Russ herself notes that while some things have changed – critics are less likely in the late twentieth century to openly denigrate women’s writing simply because of the author’s gender – others have not: said critics have found alternative ways to marginalise the writing.

I’ve been sitting on this review for nearly two months, thinking there must be more to say. There is. I’m going to post this as-is, though, because I’m not sure that I can write down all of my different reactions and thoughts coherently… and we’re going to be doing our Joanna Russ Spoilerific Book Club for Galactic Suburbia soon, and hopefully that will help me clarify some ideas. (It did!)

Victorian Debate

No, not about Queen Victoria; this is the night of the only debate between Ted Baillieu, leader of the Liberal Opposition, and Steve Bracks, current Premier and head of Labor. They are mostly just blaming each other for issues in Victoria. Now maybe I’ve been spoiled by Bartlett (and I have no doubt that I am), but these two are just so painful! Much of the time they are just avoiding the question and slanging at each other. It is sooo depressing. I think I will just vote Green. And, given the changes to the Senate, that might actually make a difference….

No more Tash

Natasha Stott Despoja announces she will not run again as a Democrat senator – in June 2008, that is, when she will have become the longest standing Democrat senator ever.

I’m a bit sad that she won’t run again, although since she has a son in a pram and has just had an ectopic pregnancy (which must be terrible), I can understand her decision too. Of course, it is almost 2 years away!

I’ve been impressed by her ever since she spoke at a UN Youth Conference I attended in 1996; she came across so well, so personably, and she was pretty inspiring too. Good luck to her, I say.