The Knife and the Serpent, Tim Pratt

I read this courtesy of NetGalley and the publisher. It’s out in a week! (Mid-June 2024.)

My first Tim Pratt novel! And yes, I can see why he’s so popular. This novel is a wild ride.

There are two points of view in the novel, which start off separate and then – inevitably – become intertwined. The first is Glenn, whose story begins with the sentence “This is how I found out my girlfriend is a champion of Nigh-Space.” Glenn is having a perfectly normal life when he hooks up with Vivian – Vivy – and finds himself falling in love, getting matching tattoos, and having the best kinky sex of his life; the dom/sub relationship is, he points out, important for understanding how they interact over the rest of the epic tale he’s telling. Which involves learning that there are multiple planes of existence, there are groups who would like to extend their control over as many as possible, and that Vivy works for one of the groups attempting to just let planets get on with being themselves, rather than ruthlessly colonised.

The second is Tamsin, who gets home one day to a weird business card stuck in her door, and then finds out that her grandmother has been murdered. With no other family around, Tamsin is responsible for dealing with the estate; when she gets to her grandmother’s house, things go very peculiar, to the point where she learns – from her embarrassing ex-boyfriend no less – that she is not actually from Earth but from a planet on an adjoining plane, and there are people who would like to use the door that allows such travel thankyouverymuch. She herself goes through the door, back to her original home, where her family – originally one of the ruling families on their planet – had been eliminated when she was a baby. You might be able to guess where it goes from here.

Eventually the two stories coincide, there are some battles and a fair bit of sneaking, a snarky spaceship compelled to wear a human suit for a while, trust issues are revealed and discussed, people’s true natures are revealed, and so on.

This book is a lot of fun. I had been very worried that this would turn out to be the start of a series – it so easily could be! There are so many planets and potential enemies! – but no, it’s a standalone, and while I think it did wrap up a bit quickly, it was also quite a satisfying conclusion. All in all, definitely worth reading.

The Fortunate Fall, by Cameron Reed

Read courtesy of NetGalley and the publisher, Tor Books. It’s out in August 2024 (and also was published in 1996, if you can somehow get your hands on an original copy).

This book is amazing and the fact that Tor is reprinting it and I therefore found out about is a very, very good thing.

“The whale, the traitor; the note she left me and the run-in with the Post Police; and how I felt about her and what she turned out to be – all this you know.”

As first sentences go, that’s breathtaking.

It seems from Jo Walton’s introduction to this edition that the people who read The Fortunate Fall when it first came out all loved it… but that ‘all’ was super limited, for whatever reason. And that’s just an absolute tragedy, because this book should absolutely be seen as a classic and it should get read by everyone and it should be discussed in all the conversations that are had about gender, sexuality, AI interactions, the use and purpose of the media, human/animal interactions, medical ethics… and probably a whole bunch of other issues that I missed.

It was originally published in 1996, and certainly some of the technology feels a little dated; the idea of a dryROM is amusing, and moistdisks are fascinating and gross. But honestly (as Walton points out) it also feels incredibly NOW. The main character, Maya, is a ‘camera’; when she’s broadcasting, people can tune in and see what she sees, hear what she hears – and experience her memories and reactions as well. This is mediated by a screener, who basically works to help amplify or minimise parts of the experience, as well as doing the tech work behind the scenes. For all that it’s from the very early period of the internet, this aspect feels prescient in terms of using social media, the difficult lines between personal and big-business media, and a whole host of other things that, again, are being thought about and talked about now. Not to mention the question of how much we actually know someone from their public-facing presentation.

And really? this isn’t even the most meaty part of the story. There’s the relationship between Maya and Keishi; that could have been the whole book. There’s Pavel Voskresenye and his experiences with genocide, being experimented on, surveillance – which could also have been a whole book by itself. And the whale. It’s honestly hard to talk about everything that is packed into this book: and it’s not very long! The paperback is 300 pages! How does Reed manage to fit so much in, and still make me understand everything that’s going on, and bring it all together such that I know it doesn’t need a sequel, and I know Maya in particular more than she would be happy with – and it’s only 300 pages in length??

I want to shove this into the hands of basically everyone I know. And then, like Walton says in her introduction, we can all talk about the ending.

Embroidered Worlds anthology

I read this courtesy of NetGalley and Atthis Arts; it’s out now.

“Fantastic Fiction from Ukraine and the Diaspora”: what a brilliant anthology.

The only theme uniting this anthology is that the authors are from Ukraine, or part of its diaspora. That means that there’s a huge range of types of stories: those that are clearly rooted in folklore (even if I wasn’t familiar with the original); those that are ‘classically’ science fiction; some that are slipstream, some that slide into horror, and a few where the fantastical aspect was very subtle. Some of the stories are very much ABOUT Ukraine, as it is now and as it has been and how it might be; other stories, as you would expect, are not.

One of my favourite stories is “Big Nose and the Faun,” by Mykhailo Nazarenko, because I’m a total sucker for retellings of Roman history (Big Nose is the poet Ovid; it starts from the moment (based on the story in Plutarch, I think) of the death of Pan and just… well. The story does wonderful things with poetry and “civilisation” and nature, and I loved it.

I loved a lot of other stories here, too. There was only one story that I ended up skipping – which is pretty good for me, with such a long anthology – and that was because it was written in a style that I basically never enjoy (kind of Waiting for Godot, ish). RM Lemberg’s “Geddarien” was magic and intense and heartbreaking – set during the Holocaust, cities will sometimes dance, and for that they need musicians. Olha Brylova’s “Iron Goddess of Compassion” is set a few years in the future, and the gradual revelation of who the characters are and why they’re doing what they’re doing is some brilliant storytelling. “The Last of the Beads” by Halyna Lipatova is a story of revenge and desperation, with moments of heartbreak and others that I can only describe as “grim fascination”.

I’m enormously impressed by Attis Arts for the effort that’s gone into this – many of the stories are translated, which brings with it its own considerations and difficulties. This book is absolutely worth picking up. If you’re interested in fantasy and science fiction anthologies, this is one that you really need to read.

Lady Eve’s Last Con, Rebecca Fraimow

Read via NetGalley. It’s out in June 2024.

I was convinced that this must have been a second in a series – even when I was a third of the way through – but it turns out that the author has just set up a truly impressive amount of backstory for this one to happen. I mean, I know most good stories have their backstory, but this one REALLY felt like I was being given the “in case you don’t remember what happened in the last book” spiel.

Ruth is a con artist. Her latest con is playing Evelyn Ojukwu, shy and slightly naive debutant, with the aim of catching the eye – and hopefully a promise of marriage – from the incredibly wealthy Esteban. But she has no intention of marrying him: instead, it’s all about the money… and here’s where the backstory comes in: because Esteban done Ruth’s sister wrong, and this is a revenge game. The fact that Esteban has an awfully attractive, Don Juan-esque, half-sister is a complicating factor that Ruth hadn’t expected.

The book is set an unspecified long time in the future; humanity has spread to many different planets and systems (it took me until maybe halfway through to realise that this book was actually set on a satellite of Pluto). The details of how all of that side works are fuzzy and irrelevant. The distances involved, though, are a significant factor – there’s no super-fast communication between planets, for instance, and the lag is a critical one for both personal and business reasons, which Fraimow uses well.

I am amused by the idea that partner-catching would still be as much of a big deal in this sort of society as it’s portrayed to be in Regency England, and that the class issues are just as real. Because that’s basically what this is – it’s a Regency-like romance, with space travel and artificial gravity. It’s fluffy (that’s a positive term!) and light-hearted, with the nods to substance that show the author is quite well aware of what they’re doing, thank you very much. If you need something enjoyable, with a bit of tension and drama but the comforting knowledge that things will turn out ok, even if it’s not clear how, this book is what you need.

The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain

Read via NetGalley and the publisher, Tordotcom. It’s out in April 2024.

To be honest I don’t even know where to start with reviewing this novella.

To say that it’s breathtaking is insufficient. I can say that it should be on every single award ballot for this year, but that only tells you how much I admired it.

I could try and explain how it explores ideas of slavery, and the experience of the enslaved; ideas of control, and social hierarchy; about human resilience and human evil. Draw connections with Ursula K Le Guin’s “The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas,” and probably a slew of stories that connect to the Atlantic slave trade and which I haven’t read (mostly because I’m Australian).

There are odes to be written to the lyricism of Samatar’s prose, but I don’t myself have the words to express that. Entire creative writing classes would benefit from reading this, and sitting with it, and gently prying at why it works the way it does.

I could give you an outline? There’s a fleet of space ships, and they’re mining asteroids, and mining is dreadful work so you know who you get to do the dreadful work? People that you don’t call enslaved but who are indeed enslaved. There’s an entire hierarchy around who’s doing the mining in the hold, and who’s a guard and who’s not a guard, and the people at the top have convinced themselves there’s not REALLY a hierarchy it’s just the way things need to be. Sometimes someone from the Hold is brought out of the Hold, and then has to learn how to be outside of the Hold… and then someone starts to see through the system, and maybe has a way to change things.

The outline doesn’t convey how powerful the story is.

I should add: the main characters are never named.

Just… everyone should read this. It’s not long, so there’s no excuse! But it will stay in your head, and it will punch you in the guts. In the good way.

These Fragile Graces, This Fugitive Heart

Read via NetGalley and the publisher, Tachyon. Out in March 2024.

A completely believable, dystopic Kansas City where the police and everything else are basically run by corporations and only for the rich (cue an Australian rant about modern USA, if you please).

An anarchic commune that’s attempting to be a place where people feel safe, and are allowed to be what and who they want – and which really gets up the nose some rich people.

A trans woman, Dora, who used to live in said commune, and left over differences of opinion about security, and has been making her way for the last few years as a security consultant.

And Dora’s ex-girlfriend, still living in the commune, who is found dead – allegedly of an overdose, but Dora discovers evidence of foul play.

This is a fast-paced thriller novella (novelette? not sure) that I devoured very quickly. Dora is complex, driven, committed, sometimes bitter, and absolutely determined to get answers, even when that might hurt herself or other people. The setting is believable and horrifying, drawn with broad strokes but enough detail that you can see Wasserstein has put a lot of thought into it; and it makes me wonder what modern KC-dwellers think of it, and if they can see the places she describes. It works as a thriller – there are twists and reveals – and just overall it’s very clever. Hugely enjoyable, and I look forward to seeing what else Wasserstein has up her sleeve.

Power to Yield and other stories

Bogi Takács (link to eir review site) sent me a copy of eir book, and I’m totally stoked I got my (electronic) hands on it. (This is eir personal site.)

Takács writes in a variety of styles across these stories. Some are fantastical, some more science-y, and many refuse classification. There are a few themes that recur: the question of identity – how we think about our own, what it informs it, how it changes the way the world approaches us – was what stood out the most, to me. There’s also a lot of questioning of authority and power, in terms of who has it, how it’s used, how it can or should be controlled/mitigated/ challenged. All of which is show that Takács doesn’t shy away from being provocative – but it’s never about just being provocative: there’s a purpose to it, because at heart it feels to me (an educator) that e is an educator – educating people about how the world and people do, could, and perhaps should function, through eir fiction. Which is not to say that the stories feel in the least bit didactic, or preachy, or anything like that! It’s more the vibe I took away from the collection as a whole.

A few favourites, not exhaustive:

“A Technical Term, Like Privilege” – not the sort of story I expect to be grabbed by, because it does have body horror as a fairly integral idea (this is me avoiding phrases like “I was absorbed by this story” because… well, story-reasons). However, the way Takács uses the issues of class and other privilege as part of the discussion is totally up my alley, and works brilliantly.

“Power to Yield” – I haven’t read any of Takács’ other Eren stories (except those collected here), so there were a few moments where I felt a bit adrift; nonetheless, it didn’t actually take away from my appreciation of the story and the characters. As with “A Technical Term,” this has more violence/ bodily harm than I would generally expect a story that I was moved by to include. But it does, and I was moved; this is a story that will stay with me a for a long time. How to build a new society, how to deal with what’s left from the old society, how to balance the needs/the good of the few and the whole… Takács doesn’t offer any easy answers to such questions, but it’s brilliant to see them confronted.

“Folded into Tendril and Leaf” – another one that includes bodily harm and warfare, and now I’m seeing an unexpected pattern! Anyway: magic, love, identity, dual perspectives; this is brilliant.

I read this collection quite slowly, because many of the stories require thinking and reflection and I didn’t want to short-change them, or myself, by simply powering through. Some of them are quite heavy in terms of the issues discussed (violence, various types of discrimination), and some are on the denser side in style (in a good way!), so ditto on the short-changing.

Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures

Yup, this one was also on special at World Weaver Press, so I grabbed it as well. I was completely intrigued by the idea of an urban focus for this sort of science fiction – that humans won’t have to abandon living in cities to survive the impacts of climate change, but they also don’t have to be the technological nightmarish warrens of Bladerunner etc. At the same time, they can’t be the same as they generally are now: where we restrict greenery to a few parks, loathe pigeons and rats as the carriers of disease, and so on. There are a few apartment buildings in my city that are starting to introduce the idea of green walls… that just needs to be taken much, much further. Which is part of what this anthology envisions.

As always, didn’t love every story, but as with Glass and Gardens there was no story that I thought was out of place. There’s a big variety in what the stories focus on – human stories that happen to intersect with animals, stories of the city itself, stories of animals and humans together. Where I said that previous anthology felt North-American heavy, this one has consciously set out to be different: there are, deliberately, a range of stories that explore the Asia-Pacific. I LOVE this.

There are a few stories where animals interact, in a deliberate way, with humans. Meyari McFarland’s “Old Man’s Sea” has orcas that have been modified for war, and how they might relate to the humans they now come across. Joel R Hunt has people whoa re able to jack into the minds of animals, in “In Two Minds,” and it’s about as horrific as you might imagine. “The Mammoth Steps” by Andrew Dana Hudson is along similar lines as Ray Nayler’s “The Tusks of Extinction,” with mammoths having been brought back and humans interacting with them… although Hudson’s version is a bit more hopeful. E.-H Nießler also has an orca-human interaction story, in “Crew;” he adds in a chatty octopus as well.

Shout out to Amen Chehelnabi and DK Mok, too: Aussies represent! Chehelnabi’s “Wandjina” is one of the grimmer stories, set basically in the middle of a bushfire, but manages to have hope in there too. Mok’s story “The Birdsong Fossil” is SO Australian, and also on the grimmer end, connecting visions of how science might be/is viewed with the de-extinction fascination; like Chehelnabi, it also ends hopefully, and is a fascinating way to conclude the entire anthology. (And Octavia Cade; NZ is totally Aussie-adjacent… plus her story “The Streams are Paved with Fish Traps” is brilliant.)

A really interesting, varied, anthology.

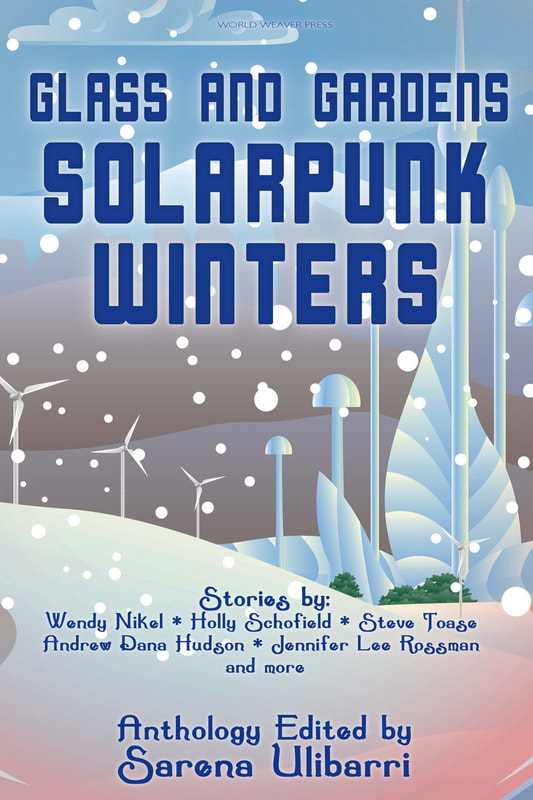

Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

I’ve only recently come across the idea of ‘solarpunk’ – basically a hopeful take on humans living in a post-climate change world, as far as I can tell. I guess this is what ‘hopepunk’ also aims to be? maybe solarpunk is a bit more about the actual mechanics… I don’t know, I’m not going to claim the ability to set genre boundaries. ANYWAY, World Weaver Press has done a bunch of solarpunk anthologies, and a couple of them were on special the other day so I got them.

The first one I read was this, Glass and Gardens. Turns out I was in the right zone for some hopeful SF. As with all anthologies, I didn’t love every story – but also, there were no stories that left me wondering what the editor was thinking. They all fit the overall theme – how to be hopeful when winters have got more extreme or, in a couple of cases, the world has warmed so much that winter no longer happens, with equally disastrous consequences for the environment. It is heavily North American-focused, but honestly as an Australian this is just something I pretty much take for granted.

One thing I particularly liked was that while all of the stories were focused on humans, and what they are doing to live with/ mitigate/ work around climate change, there’s also a focus on how the climatic changes have affected the rest of the species on the planet. It’s s refreshing change and something that seems to be a trope within solarpunk from what I can tell – an acknowledgement that humans aren’t alone on the planet. So there’s Jennifer Lee Rossman’s “Oil and Ivory”, about narwhals and whether they’ll be able to travel underneath pack ice in the Arctic; bears and several other animals in “Set the Ice Free,” from Shel Graves; and several stories that have cities encouraging a lot more greenery and what could be called extreme eco-living compared to today.

An aspect that connects to the idea of hope is the prominence of art in these stories. Your dire post-apocalyptic world has no room for art and beauty. But Sandra Ulbrich Almazan has characters making clothes in a variety of ways in “A Shawl for Janice;” “On the Contrary, Yes” from Catherine F King is entirely focused on art and making art across multiple genres; Andrew Dana Hudson imagines ice-architecture as its own art form in “Black Ice City.”

This is a great anthology, and I look forward to reading more solarpunk.

Rosalind’s Siblings – anthology

I heard about this anthology c/ Bogi Takács, the editor, and the premise immediately grabbed me (also I trust Bogi’s sensibility). It can be bought here.

The premise here – as the subtitle says – is speculative fiction stories about scientists who are marginalised due to their gender or sex, in honour of Rosalind Franklin – a woman whose scientific discoveries were key to the unravelling of DNA, but who never received the recognition that Watson and Crick did in their own time.

In Takács’ introduction, they note that the stories don’t take a simplistic view of science; there are stories where science is generally a positive force, and stories where it’s not. There are a variety of different sciences presented, a variety of ways of doing science, and a variety of contexts as well. There’s also a range of characters, across gender and and sexuality and neurodiversity and experience and ethnicity and everything else. This reflects the authors themselves, who are also really diverse. The stories, too, vary in their speculative fiction-ness; near-future, far-future, magical realism, on Earth or in the solar system or far away. There are two ‘trans folk around Venus’ stories, as Takács rather amusedly notes – and they are placed one after the other! – but they’re so different that I’m not sure I would have clicked to that similarity without having been made aware of it from the introduction (stories by Tessa Fisher and Cameron Van Sant; they’re both a delight).

As with all anthologies, I didn’t love every single one of these stories – that would be too much to expect. But there were zero stories where I wondered why an editor would include it, and all of them fit the brief, so those are pretty good marks. DA Xieolin Spires’ “The Vanishing of Ultratatts” was wonderful and hinted at an enormous amount of worldbuilding behind the story. Leigh Harlen’s “Singing Goblin Songs” was a delight, “If Strange Things Happen Where She Is” (Premee Mohamed) has gut-wrenching timeliness (science in a time of war), and “To Keep the Way” (Phoebe Barton) utterly and appropriately chilling.