Curtsies and Conspiracies

This is another hugely enjoyable book from Carriger. Once again our girl Sophronia is thrown into difficulties at her alleged finishing school. This time she has a lot more to do with the supernatural element of her world, especially the vampires. Of course there’s a lot of discussion of dresses and fashion and hats and reticules; she must figure out how to carry a knife without it being obvious, she must learn to bat her eyelids effectively, and how best to carry the implements required of a young lady in her position. I’m still surprised by how enjoyable I find yet another school focused book.

This is another hugely enjoyable book from Carriger. Once again our girl Sophronia is thrown into difficulties at her alleged finishing school. This time she has a lot more to do with the supernatural element of her world, especially the vampires. Of course there’s a lot of discussion of dresses and fashion and hats and reticules; she must figure out how to carry a knife without it being obvious, she must learn to bat her eyelids effectively, and how best to carry the implements required of a young lady in her position. I’m still surprised by how enjoyable I find yet another school focused book.

Most of this book is spent on the dirigible of Miss Geraldine’s finishing school. Some time is spent in classes, learning about domestic economy, poisoning, fainting and how to properly address vampires. But for Sophronia, much of her time is spent on the outside of the dirigible – climbing – as well as with the sooties down below and the dressing-as-a-boy Vieve. Interestingly the plot follows on from Etiquette and Espionage, in that the MacGuffin here is the same. Of course this time it’s not so much about finding the prototype as it is about figuring out what it can do, how it will do it, and who will control it. There’s a surprising amount of politics for a book that seems at least on the outside as being solely can send with fashion. I guess that’s kind of the point; that the two don’t have to be mutually exclusive and anyone who is thinks they are is likely to underestimates graduates of Miss Geraldine’s finishing school.

One of the big differences in this book compared to the original is that there’s a lot more boys. I’m not really sure what I think about this; on the one hand it’s obviously an important skill for girls like Sophronia and Dimity to learn – that is, how to deal with difficult yet handsome young man. And of course reappearing in this book is Soap, certainly one of my favorite characters although somewhat problematic given that he’s black and his nickname is Soap. On the other hand I really enjoyed the almost exclusively female cast of the first book; the fact that boys were not necessary for the book to proceed, the fact that the girls were perfectly capable of getting themselves into and out of scrapes generally without any male assistance (or hindrance) at all. While some of the ways that Sophronia dealt with her would-be suitors was entertaining, I did find myself enjoying the sections of the plot that solely involves the girls generally more enjoyable.

I continue to be fascinated by the development of this world that Carriger initially developed for the Alexia books. And of course I remain desperately keen to find out how this series will intersect with the earlier one. One of those intersections is quite obvious but I have no doubts that Carriger will provide some further surprises in the rest of the series.

The Farthest Shore

For a book written for children – perhaps a young adult audience – this sure is a bleak book. It’s also a deeply philosophical book, as well as having a great deal of adventure and learning about life. It’s the most Tao book of Le Guin’s Earthsea series. It’s an odd book to come after The Tombs of Atuan, as that was after A Wizard of Earthsea; the pace is so different. I think Wizard must come first but for these two the order is irrelevant. It’s also back to bring an almost exclusively male narrative.

For a book written for children – perhaps a young adult audience – this sure is a bleak book. It’s also a deeply philosophical book, as well as having a great deal of adventure and learning about life. It’s the most Tao book of Le Guin’s Earthsea series. It’s an odd book to come after The Tombs of Atuan, as that was after A Wizard of Earthsea; the pace is so different. I think Wizard must come first but for these two the order is irrelevant. It’s also back to bring an almost exclusively male narrative.

I know young adult books are often bleak; we have a rash of dystopian novels to prove that. But in roughly 170 pages Le Guin explores the consequences of rushing off after life at the expense of losing life; of fearing death so much that you give up on life; and the sheer loss of hope, and what that might do to society. Somehow the fact that Le Guin does it so quickly makes it seem more bleak. Like the first book

this book is about one quest, one search for one man. Instead of taking an entire trilogy, with lots of disappointments and setbacks and newfound friends, Le Guin has Sparrowhawk, now with a new young friend, simply track that man down. Of course it’s not really a case of doing anything “simply”. There are set backs. The book does show us more of Earthsea and its environs, and we meet a variety of different people; but everything is designed to assist in the one quest. And as I said before, it is only 170 pages. Le Guin’s words are evocative and precise. There is glorious description, but it doesn’t go on forever. Characters are swiftly sketched. Swiftly, and brilliantly. The story is as driven towards its conclusion as Sparrowhawk is towards his.

We always knew that Sparrowhawk would turn out to be the archmage. We were told that in the first book. And here he is, Archmage for five years, now being confronted by something strange going on to the south and to the west of the Inner Lands. Unsurprisingly Sparrowhawk is feeling confined by the walls and the tasks and the requirements of being archmage. It’s not clear how long after the events of the previous books this is happening. And in some ways, as the book reminds us, it doesn’t really matter. Sparrowhawk has had a long and distinguished and occasionally difficult career as a sorcerer. Many of those deeds get recorded in the songs made about him at some point in the future. This is another one to add to his long list. Of course, he is not the only – and perhaps not even the main – protagonist of this book. He is joined by a young prince, perhaps just slightly older than Sparrowhawk himself was in A Wizard of Earthsea. It’s therefore a coming-of-age story for young Arren, as that book was for Sparrowhawk. Not that Sparrowhawk doesn’t have a lot to learn: about himself and about his world and about what must be done.

Life and honour and death and hope and love and fear. What more could an author hope to explore?

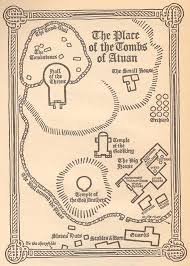

The Tombs of Atuan

While there’s a similar feel in the language – sparse and intense – this is a very different book from A Wizard of Earthsea. It’s bound to just one place; it’s focussed on a girl. The struggle for identity is similar but Tenar/Arha has less agency than Ged, which is understandable given her very different situation. There’s very little magic.

I might love this more than A Wizard of Earthsea.

It’s so… peculiar. It’s simple enough to find parallel stories – mythic ones, modern ones – for Ged, since he is basically a young man finding his purpose and his way in the world. It’s a coming of age story, if not ‘simply’. For Arha though… the situation is different. It’s still a coming of age story; it is about Arha finding her purpose and place and understanding the world. But it’s focussed so tightly on the Place that it feels completely different. Is there a difference in a girl coming of age and a boy? Certainly in terms of myth there is, and Le Guin is, I think, interested in writing Myth in these stories. In fact she makes some quite obvious comments about mythology; we know, in A Wizard of Earthsea, that Ged goes on to become something great (how’s that for foreshadowing and reassurance?), and that there are stories about him. Arha is basically living a myth.

It’s so… peculiar. It’s simple enough to find parallel stories – mythic ones, modern ones – for Ged, since he is basically a young man finding his purpose and his way in the world. It’s a coming of age story, if not ‘simply’. For Arha though… the situation is different. It’s still a coming of age story; it is about Arha finding her purpose and place and understanding the world. But it’s focussed so tightly on the Place that it feels completely different. Is there a difference in a girl coming of age and a boy? Certainly in terms of myth there is, and Le Guin is, I think, interested in writing Myth in these stories. In fact she makes some quite obvious comments about mythology; we know, in A Wizard of Earthsea, that Ged goes on to become something great (how’s that for foreshadowing and reassurance?), and that there are stories about him. Arha is basically living a myth.

I’m fascinated by Arha. I love Le Guin’s exploration of the fact that she is a wilful young girl – and who wouldn’t be, being told that they are the First Priestess reborn, and basically untouchable by any of the people around her? When you are so set apart from those around you, it makes sense that you would become aloof and indifferent. And yet Arha is also vulnerable; she fears Kossil, the High Priestess of the Godking, but also relies on her. She is overcome by her fear of the dark, when first taken to the Undertomb, and then overcomes the fear in turn. I can imagine that, left to her own devices, she would have become quite formidable… within the restricted space she can access.

This is a claustrophobic novel. Where A Wizard introduces the reader to many parts of Earthsea, this one only really allows us to see one remote, nearly forgotten, temple complex. And yet the plot itself doesn’t feel that constrained, perhaps because – for most of it – Arha doesn’t notice it. It’s a testament to Le Guin that she makes such a small area so intensely powerful and important.

I had forgotten how much I love this book. In fact, perhaps I didn’t used to love it so much, and this is a reflection of greater maturity… I guess I read this in early high school, and I don’t think since. Onwards to more Le Guin!

A Wizard of Earthsea

I first read this… I don’t remember when. I think I was at primary school. And I’m not sure whether I’ve read it since, but it had a very big impact on me. I could still remember a lot of the little details, and my fierce appreciation, fear, and sympathy for Ged.

A friend who read this as an adult just couldn’t cope with Le Guin. It made me think that perhaps Le Guin is like a really amazing pencil sketch, where someone like Martin or other such epic writers are oil painters. Le Guin doesn’t waste words; she doesn’t give lush, page-long descriptions. But this isn’t a detraction; she’s evocative and masterful in her language, and she tells a grand tale in (in my copy) well under 200 pages. That’s not something to be frowned upon! … but it could be something that people with tastes shaped by more modern fantasy writers find hard to cope with. And that’s fine; it’s just a different tastes thing.

A friend who read this as an adult just couldn’t cope with Le Guin. It made me think that perhaps Le Guin is like a really amazing pencil sketch, where someone like Martin or other such epic writers are oil painters. Le Guin doesn’t waste words; she doesn’t give lush, page-long descriptions. But this isn’t a detraction; she’s evocative and masterful in her language, and she tells a grand tale in (in my copy) well under 200 pages. That’s not something to be frowned upon! … but it could be something that people with tastes shaped by more modern fantasy writers find hard to cope with. And that’s fine; it’s just a different tastes thing.

I love that Le Guin starts with Ged as a wild young thing. I read somewhere that when she was commissioned to write a children’s book she looked at the wizards she knew and they were all old men (she’s a big LOTR fan), and she thought: how did they get there? So forty years before Rowling, she wrote of a wizard school. And Ged is nothing like Harry.

The friendships are wonderfully understated but nonetheless feel real; the dangers are never dwelt on in horrific detail but are nevertheless palpable. Ged’s efforts, his fears, his determination – all come through. Perhaps this is why I appreciate Rosaleen Love: her sparse language is a lot like Le Guin’s, and they both manage to capture a great deal in few words.

I also love that the only white-skinned people in this story are the invading barbarians, who only occupy a few pages.

Chimes

This book was provided by the publisher.

I’m a little conflicted by this book, and I know I won’t write a review that does it, or that ambiguity, justice.

On the one hand this is a book of gorgeous prose. It’s lyrical (heh) and it’s evocative, setting up beautiful word-pictures. This is a world where although sight still exists, hearing has become far more important for many people – an inversion of today? There’s talk of whistling directions, of using tunes as advertisements and as aides memoire, and then there’s Chimes. Chimes is music that plays at Matins and Vespers, and no matter where you are (well, within the small geographic scope of the novel) you have to pay attention. It’s fairly fast-paced; Smaill does a good job of showing the dystopian nature of the world without a whole lot of detail; I found the conclusion satisfyingly dramatic.

On the one hand this is a book of gorgeous prose. It’s lyrical (heh) and it’s evocative, setting up beautiful word-pictures. This is a world where although sight still exists, hearing has become far more important for many people – an inversion of today? There’s talk of whistling directions, of using tunes as advertisements and as aides memoire, and then there’s Chimes. Chimes is music that plays at Matins and Vespers, and no matter where you are (well, within the small geographic scope of the novel) you have to pay attention. It’s fairly fast-paced; Smaill does a good job of showing the dystopian nature of the world without a whole lot of detail; I found the conclusion satisfyingly dramatic.

On the other hand… there are enormous questions that are never answered about how ‘the world’ got like this (there’s hints but that’s all), whether the entire world is like this or just some area around London, and there are a few plot holes here and there that are glanced over. What I can’t figure out is whether these things matter or not. On balance, I think I can live with those problems, and it’s mostly because of the beauty of the language. If this were a more pedestrian novel I would have more problems with it. The one problem with the language is the use of musical terms. No one does anything quickly or slowly; it’s all piano, lento, tacet… and I don’t even know if some of the words were invented. I have zero musical training so there were times where I was confused about whether we were rushing or going stealthy. Still, I coped. I was a bit sad at about the halfway mark that the novel was so boy-heavy (I hadn’t read the blurb so I actually thought the narrator was a girl, at the start), but by the end I was a bit more content with the gender choices overall.

The novel is written in the first person and in present tense; I feel like I haven’t read a whole lot of present-tense stuff recently, so that was intriguing. Our protag is off to London with a mission from his dying mother, but he has to hurry because he’ll lose his memory of what he’s doing pretty soon. Because everyone does. This is a world where people are just about living Fifty First Dates. They keep ‘bodymemory’ – usually – so they remember how to eat, how to do the manual parts of their job, and so on; and maybe ‘objectmemory’ can help with some specific events… but unless relationships, for instance, are renewed every day, pretty soon those people are gone from your mind. Because of Chimes. The music you can’t not hear.

Simon, of course, is a bit special – he’s got a slightly better memory – and while the whole You’re Special thing might be a bit old, that’s because it’s such a good way of making change happen in a difficult world. Anyway, Simon starts finding out more about his world, thanks to a new friend, and things progress from there. I liked Simon, overall, as a voice for showing the world, but really we don’t find out that much about him – I think as a factor of the first-person narration. That’s not necessarily a problem; you’re enough in his head on a day-by-day basis that I, at least, certainly cared what happened.

The musical aspect is original, at least in my reading experience, and the prose is a delight. For a debut novel I’m even more impressed – and not surprised to discover that Smaill is both a classically trained violinist and a published poet. I hope she gets to publish more books, and I hope this features on the Sir Julius Vogel ballot next year (she’s a Kiwi). You can get it from Fishpond.

A Face like Glass

There is an exquisite agony in expectation.

A few years ago I read Gwyneth Jones’ Bold as Love sequence. I owned all of the books but I read them over almost a year… because it was kind of almost fun to wait, even though I had no need; and because I didn’t want the ride to be over.

Last year I did the same with Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series (which still isn’t finished because I haven’t got around to finding the last two), and Sarah Monette’s Mirador.

I had Frances Hardinge’s A Face Like Glass sitting on my desk for a full week, waiting to be read. It’s not exactly a year, but the principle is the same: knowing that I had it there waiting to read was incredibly exciting; knowing that as soon as I started reading it would soon be over was excruciating. Because oh my Hardinge is a glorious, glorious author.

I had Frances Hardinge’s A Face Like Glass sitting on my desk for a full week, waiting to be read. It’s not exactly a year, but the principle is the same: knowing that I had it there waiting to read was incredibly exciting; knowing that as soon as I started reading it would soon be over was excruciating. Because oh my Hardinge is a glorious, glorious author.

And now I’ve read it and it was as I expected – which is to say even better than I expected – but now I am FINISHED and I am BEREFT.

A curmudgeonly cheesemonger is so antisocial he just lives in the tunnels with his cheeses (no ordinary cheese, it should be said, but cheese that can make you see visions and hear songs and maybe spit acid at you. TRUE Cheese). One day he finds a girl in a vat of whey… and her face: well, he makes her wear a mask.

Now, you might be thinking this guy is a bit odd. And he is. But the society he’s turned his back on is that of Caverna; they all live underground. And the other thing that’s different about them is that as babies, they don’t learn facial expressions. At all. Babies, toddlers, even adults if you’ve got the money, have to learn Faces: initially from family, and then from Facesmiths. Yes, this is as weird as it sounds… and it ends up being a really interesting reflection on class issues. Once you’re an adult, it costs a lot to learn new and interesting Faces; so of course, the poor don’t. And can’t. Does that mean they don’t have the emotions that require such a range of emotions?

Indeed, what does it mean to feel an emotion if you can’t express emotion via your features? Hardinge doesn’t pretend to have all the answers, but she makes a compelling, swoon-worthy novel from the issue.

It’s not all cheese and frowns, though. There’s also intrigue, friendship, losing your way, kleptomancy (my new favouritest way of telling the future), True Wine and Cartographers whose words can make you go crazy. There’s recognising your own emotions as well as others’, figuring out who to trust and how to trust yourself, and the willingness to Go With The Crazy.

And then there’s the glory that is Hardinge’s prose. Her words don’t just flow; sometimes they trickle and sometimes they gush but they always worm into your brain and create stunning pictures and magnificent juxtapositions. I’m pretty sure I could read Hardinge’s shopping list and it would be a work of lyrical beauty.

Get it from Fishpond. If you have never read a single Hardinge, read this one… and then read the rest….

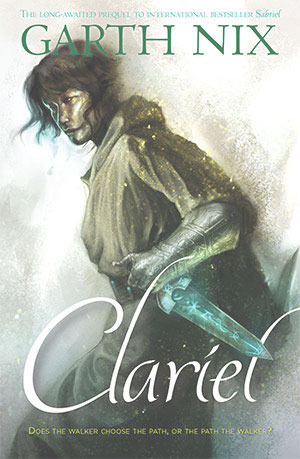

Clariel

Some spoilers for the Abhorsen trilogy at the start; spoilers for this book at the bottom, and flagged.

Some spoilers for the Abhorsen trilogy at the start; spoilers for this book at the bottom, and flagged.

Clariel is another wonderful addition to the world of the Old Kingdom, with magic (good and bad), Abhorsens dealing with the dead, and a complex and compelling young woman growing up in a difficult world with a difficult family. There’s adventure and misadventure, a few friends, unwanted romance, moving to a new place and being forced to do what you don’t want to do. A lot of people – I’m going to assume, anyway – will be able to identify with Clariel being forced to go somewhere and consider a future that are neither of her own choosing; I could absolutely identify with her desire to just be left alone. The first is something that young adults are often dealing with in novels; the second is rarer, and it was really nice to see, rather than always having it suggested that gregariousness and being in groups is automatically a good thing and to be desired.

There was one thing that frustrated me enormously, and it has nothing to do with the plot and everything to do with my desire to see sentences constructed well: there were far, far too many comma splices. They prevent sentence flow and sometimes they actively interfere with meaning making. And now I can’t find any examples but THEY ARE THERE.

For those of us who know and love the ‘original’ Abhorsen trilogy, Clariel (set 600 years before Sabriel) is a little bit unbearable. While those books take place in an Old Kingdom bereft of a king, at least the Abhorsen is doing his job – and I submit that the Abhorsen making sure that the dead stay dead, and that necromancers aren’t being evil, is of more immediate import than a king making laws. Yes the lawlessness helps the necromancers, but at least the Charter Magic is strong and there is someone to combat the problems. … I found this excruciating.

And…

SPOILERS!!

When I first heard about this I thought it was a sequel, and I was kinda hoping for a continuation of Lirael. Then someone told me it was a prequel, and I immediately wondered if it was the story of Chlorr of the Mask given it’s suggested she was an Abhorsen and OMG I WAS RIGHT. I was SUPER excited to realise that Clariel would indeed eventually become Chlorr, and I loved how Nix made this more and more obvious but actually only confirms it right at the very end – in fact not in the story proper. Of course it’s pretty obvious when she puts on the mask. And I really love that this book absolutely stands alone… and actually now it occurs to me that I kinda wish Nix hadn’t confirmed her as Chlorr, because that’s a spoiler for people who come to this fresh. Sigh. Anyway, this is probably the darkest of the Abhorsen books so far, but perhaps only for those of us with knowledge of the future: it looks like Clariel could possibly avoid Free Magic, although of course that conniving Mogget certainly is going out of his way to make that not be the case. MOGGET. That treacherous beast. Imagine coming to Sabriel etc knowing what Mogget is actually capable of! That’s going to really influence your reading. I was intrigued that there was no connection with the non-magic world, given how wide-ranging it is otherwise, and the suggestion that the Old Kingdom and magical territory apparently extend quite a lot further than might be guessed from the original books. And how on EARTH does the Abhorsen family fall so far?!?

I’m excited that Nix is writing another in the Old Kingdom, too – this time following on from the original set!

A Million Suns

I loved Across the Universe, the first of Beth Revis’ series about a generation ship. I was really excited about the sequel and bought it ages ago… and have only now read it, as part of my Read the Books I Own but Haven’t Read thing.

Sadly, I was disappointed.

Spoilers for Across the Universe and A Million Suns.

Spoilers for Across the Universe and A Million Suns.

The story picks up pretty much where the first one left off, again alternating between Amy – awakened before time on a generation ship that’s meant to be racing towards a new planet for colonisation – and Elder, now officially the one who’s in charge of the ship and the one who woke up Amy when he wasn’t meant to (which, the more I think about it, CREEPY. Which gets addressed briefly here but not enough). The book revolves around the issues confronting the population now that they’re off the drug that’s been in the water, keeping them all nicely docile, which also means that they can now realise that they’re being led by a sixteen year old boy (an issue which is only briefly addressed).

The good: I continue to like the exploration of generation ship issues. While I have some problems with how it’s done, it’s nonetheless good to see it done at all. If you’ve grown up in a tin can, it makes sense that at least some people are going to find the idea of not having walls utterly terrifying. It also makes sense that some people are going to resent begin, effectively, just a means to an end – why do stuff for people, and a destination, that you’ll never see? I was glad that Revis addressed some of the issues of resources and the problem of being a closed system, even if not in great detail.

I liked that people started thinking about political change. I can’t decide whether that happened too quickly or not, but it amused me greatly to see the French Revolution being referenced.

There are some pleasing aspects in Amy and Elder’s relationship. I really like the discussion of whether, if you only have one possible choice, falling in love with that person is real. There are too many examples of that just happening, as if OF COURSE I love you because you’re in front of me. Of course, this ignores the fact that people don’t necessarily fall in love with people of their own age – as demonstrated by Victria – which makes Amy’s flailing about do I/don’t I a bit precious. As mentioned above I really liked that Elder’s fascination with frozen Amy was revealed to Amy, even if it was only briefly an issue for her when I think it should have been more significant.

Overall, the writing is smooth; it’s not hard to read.

The bad: look, I don’t think I’ll read the third. That should tell you enough.

Amy and Elder both drove me nuts at different points. Amy whinges a lot, and Elder is alternately arrogant and fearful and it didn’t always make sense in context. Their relationship bugged me, especially towards the end – and I got annoyed because much of the story is about their relationship. When I realised that really, this is a love story that happens to be set in space, I got a bit less annoyed. Because that’s totally fine: it’s not what I was expecting or hoping for, but it’s a perfectly fine choice for Revis to make. Except that the story of their love just didn’t interest me that much – but that’s an issue of story telling rather than story choice.

To move on to the plot – Orion setting clues for Amy so that she finds out the truth about the ship was just ridiculous. It makes no sense for Orion to have done that, since I don’t think it’s suggested anywhere that he was sadistic. One clue, leading Amy to discover a video of Orion explaining the truth about the Godspeed, would have made sense. Or leading her to the space suits so that she could go out and see the truth for herself – that would have been fine too. But this convoluted trail that relied on Amy, a seventeen year old, having read certain stories and paying any attention to the shelving of books… seriously. No.

And the great reveal? I absolutely guessed that the ship was stationery, having already arrived. I think that the idea of people refusing to go down because of wild animals is weak, and the suggestion that people would not have earlier made exactly the decision that’s made at the end of the novel – of splitting the population – is ludicrous. The only thing that kept me reading this was to find out how the generation ship aspect was dealt with; I do not care enough to read about the population trying to make their way on the dirt.

The Crooked Letter

I’ve read this as part of my great Read Everything I Own but Haven’t Read Yet pledge, which I’m hoping to make serious inroads into this year. We’ll see…

I got this a number of years ago as part of a show bag at a Swancon. I had read some Williams before, but not much. Since then I have read large chunks of his SF, but – until now – none of his fantasy except for the Troubletwisters books with Garth Nix. (It’s actually been a while since I read much fantasy at all, which is curious to realise.)

I got this a number of years ago as part of a show bag at a Swancon. I had read some Williams before, but not much. Since then I have read large chunks of his SF, but – until now – none of his fantasy except for the Troubletwisters books with Garth Nix. (It’s actually been a while since I read much fantasy at all, which is curious to realise.)

Slight spoilers!

Williams clearly has a thing for twins. In this, the twins are mirrors of one another, down to one of them having his heart on the righthand side of his chest. Their names are Seth and Hadrian – and I’ll admit to being a bit disappointed with the name choice, given that both lend themselves to some nice tricksy name-association, just not with each other. Moving on… Seth and Hadrian are on holidays in Europe. They end up travelling with a girl, Ellis, and then everything gets weird when one of them is stabbed. That’s not the weird part, though – the weird part is the non-stabbed one waking up and realising that the world is very, very different from when he last had his eyes open. And then things just get worse. For both of the twins.

There are some really nice elements to this story. Overall I thought the twins’ relationship was a well-developed one, nearly perfectly balanced between love and… not hatred, but perhaps despair at being tied to this same person in so many ways for so long. Occasionally I got a bit bored by the whinging, but perhaps that’s teenagers for you. The cherry-picking of mythology and characters from all over the world was a nice touch – it certainly avoided being eurocentric, which is always nice to see, and plays into a bit of a Jungian idea of the great subconscious with these commons themes that can (maybe) be seen. And I especially loved that Hadrian’s adventures mostly took place in a city – THE city, the great underlying city, what every city dreams of being. While I do love me some epic horse-riding and camping out, grand fantasy played out on city streets also has a lot of appeal.*

There are, though, some aspects that grated. Hadrian’s absolute insistence on finding Ellis – and that people are willing to help – strained credibility: HELLO, everyone ELSE appears to be dead, so how exactly are you planning on finding one probably-dead girl in the great uber-city? I was hoping right from the start that Ellis was going to turn out to be more than just a girl, and that all of the non-humans knew it, since that would excuse it to some extent. The first was correct but not the second, so my annoyance with that plot element still exists. Sometimes the mashing of multiple mythologies did not gel for me, and the explanation of the Three Realms really didn’t work for me. I can’t explain why; I don’t think it’s my faith getting in the way, since it rarely does with this sort of fantasy (that is, the sort that’s clearly playing with pagan ideas, rather than Crystal Dragon Jesus types).

I did finish it, which means I did enjoy it even if I didn’t adore it. I own the second Books of the Cataclysm, The Blood Debt. While it’s not next on my list, I will definitely be reading it at some point… and from there I’ll see whether I get around to the other trilogy that this is actually a prequel to, the Books of the Change.

You can get The Crooked Letter from Fishpond.

*Hmm. Do I need to read Lord of the Rings again sometime? I’m getting an itch…

Alanna #2: In the Hand of the Goddess

A while back, I read Alanna: the First Adventure. I said at that time that I would read the rest of the quartet at some point, but I wasn’t in a screaming hurry. Then the other day on Galactic Suburbia, Tansy announced that she was commencing a re-read. Well, I couldn’t let her re-read beat my initial read, could I? What if she said spoilery things?? So, I went out and borrowed the next three. And read them…

SPOILERS

So. The second book. First off, let’s talk about this cover. It’s from the 2011 re-release, and it is less than awesome. Her horse’s name is Moonlight, fercryinoutloud. At least she’s got a sword and is dressed in squire-ish clothes. Secondly, let’s talk about where I found it: in the junior section of the library. Not the YA section; the junior section. I can maybe see the first book fitting there, but not the entire series. I found that weird before I read them, and then as I read the casual attitude towards sex – the sex isn’t explicit, in the slightest, but it is very clearly present – I was even more astonished. Also, the killing of people with swords, which again isn’t the most graphic violence but still, not sure you’d want a ten year old reading it. Thirdly, the title… well, it makes sense in some ways, but it doesn’t inspire me and in fact makes me roll my eyes. I would not pick this up based on the title. (Of course I would already have been put off by the cover of this particular edition.)

Anyway. The story picks up with Alanna now being squire to Jonathan, the prince, who knows that she’s actually a girl. The story essentially covers her progression towards becoming a knight. It covers three or four years in 240 pages. Sometimes you blink and it’s a year later. Some writers carry that off with aplomb – mostly I’m thinking of Ursula le Guin here I think – but I’m not entirely convinced of it by Pierce. Over that time, Alanna acquires a cat, Faithful (many of the names that appear in this series I am entirely unimpressed by); a lover, in Jonathan; and of course becomes a knight. And, in a very rapid turn of events, she kills her nemesis, Duke Roger. That particular bit happened so fast my head was spinning.

Alanna grows up, as she needs to, and generally that’s well done. She frets about things fairly convincingly. It was good to see that Pierce allowed Alanna’s friends to accept her being a girl relatively easily; that she had proved herself enough that it was straightforward for them to still see her as a knight.

Battle scenes aren’t dwelt on, which I appreciated. The aftermath, though, is not ignored; Alanna throws up after her first real skirmish, the patching up of soldiers is shown in as detail as the battle itself – which isn’t glorified – and when Alanna isn’t able to fight, she goes off and helps the healers. I like how practical Alanna is; I like that the reality is shown, although of course Alanna is Super Gifted in every area necessary (which sometimes does get a bit wearing).

Jonathan is a bit boring. I was surprised when he and Alanna fell into bed together relatively easily; later, there is a suggestion that this diminishes Alanna’s virtue in some eyes, but she doesn’t worry about it at this stage. I can’t help wondering about the power issues of a prince sleeping with a vassal – although of course this has always happened in history – but also the rather weird situation of a knight sleeping with his squire… although of course this may well have happened in history….

As a rogue, George of course is more interesting. I’m a bit impatient with love triangles though.

Really, this book gets through things extraordinarily fast.

You can get In the Hand of the Goddess from Fishpond.