Tomorrow’s Parties (anthology)

I really have to be in a particular frame of mind to read anthologies, which is why I read several in a row recently – including this one. It’s not that I thought I wouldn’t enjoy them – they’re Strahan anthologies, I’ve never not enjoyed one. It’s just a particular reading experience.

Anyway! Now I have read this awesome anthology and it was as stunning as I expected. As the subtitle suggests, the loose theme is “life in the Anthropocene”, and the authors largely took a similar-ish attitude towards what that means; there’s a lot of climate change-related stories, as is appropriate, and / but all of the authors took quite different approaches to what that might mean.

Every single one of these stories is amazing. I’m intrigued that Strahan chose to open the anthology with a conversation between James Bradley and Kim Stanley Robinson – it’s the sort of thing that I tend to expect at the end of the anthology – and maybe that’s part of the reason for it to be up front: to encourage readers to actually read it. It also sets up the climate change issues that are so front and centre through the rest of the book; the title is “It’s Science over Capitalism: Kim Stanley Robinson and the Imperative of Hope,” which itself speaks volumes.

The ten stories in this anthology are all exceptional.

Meg Elison, “Drone Pirates of Silicon Valley”: the future of online shopping and delivery, yes, but also rich vs poor, and the future of capitalism.

Tade Thompson, “Down and Out in Exile Park”: how communities might live differently, and how that challenges the status quo.

Daryl Gregory, “Once Upon a Future in the West”: multiple perspectives, and quite creepy at times. So many issues – the (negative) future of telehealth appointments, autonomous vehicles, bushfires…

Greg Egan, “Crisis Actors”: a very disturbing story that explores some of the consequences of living in a “post-truth society”. I always adore Egan’s short work.

Sarah Gailey, “When the Tide Rises”: another story that confronts capitalism head-on, bringing back the idea of the ‘company town’ as well as poking at the idea of companies making money from finally doing good for the planet. Brilliant.

Justina Robson, “I give you the moon”: one of my favourites, and not just because it’s one of the most hopeful of the stories. This is post-climate crisis, when humans have figured out how to live in more balance with the rest of the world (her vision is marvellous). Rather than focusing on how we get there, this story is about family dynamics, and ambition. It’s gentle and wonderful.

Chen Qiufan (trans. Emily Jin), “Do you have the Fungi sing?”: the consequences of a hyper-connected world, what happens if an area doesn’t want to participate – and possible alternatives.

Malka Older, “Legion”: completely and utterly different from all of the others, this is the story that’s going to stay with me the longest. Chilling, confronting, challenging… I had to stop reading when I finished this story and take a breath. It takes place over a short period of time – maybe an hour? – in the prep for, and during, an interview on a talk show. The host, Brayse, is interviewing a woman representing Legion, a group who have just won a Nobel Peace Prize. The reader is in Brayse’s head, which starts off as a reasonable experience and then gets… less so. Legion, as the name suggests, are not just one or a small group; they are everywhere, always watching through wearable cameras, and able to call out – or respond to – what they see: micro- and macro-aggressions, and all the ways in which some people are made to feel less comfortable right up to actual harm. Older nails the unfolding of this story perfectly.

Saad Z. Hossain, “The Ferryman”: another incisive take on the consequences of late-stage capitalism, this time how people will respond to death when, for the ‘haves’, death doesn’t need to exist.

James Bradley, “After the Storm”: being a child growing up in the ravages of climate change is likely to suck; at the same time, children do tend to be resilient and make their way within the world that they know. Bradley focuses on teenagers and their experiences – rather than the adults who know how things have changed – and captures the cruelty as well as the love of adolescents beautifully.

All in all, an excellent addition to the literature around ‘what next’.

Someone in Time (anthology)

I am late to the party… however, not SO late, because this just won the British Fantasy Award! Which it absolutely deserves.

I’m sure there are some readers who would avoid this because “they don’t read romance” (hi, I used to be one of those). The reality though is that you do; there’s almost no story – written or visual – that doesn’t include romance somewhere in its plot. What I have learned about myself is that I rarely enjoy what I think of as “straight romance” – that is, stories where the romance is the be-all of the plot; they just don’t work for me, as a rule. What I love, though, is when the romance is absolutely integral to the story and there’s a really fascinating plot around it. Every single one of these stories does that.

As the name suggests, this is set of stories involving romance and some sort of time travel. It’s a rich vein to mine, and every single one of these stories is completely different. Sometimes the time travelling is deliberate, sometimes not; sometimes the ending is happy, other times not; some are straight, some are queer; some pay little real heed to potentially disrupting the historical status quo; some have easy time travel while others do so accidentally; sometimes the time travel happens to save the world, and sometimes it’s about saving a single person. Sarah Gailey, Rowan Coleman, Margo Lanagan, Carrie Vaughn and Ellen Klages (a reprint) wrote my favourite stories.

And then there’s Catherynne M Valente’s piece. I did love every single story in this anthology; Valente’s story is breathtakingly different in its approach to both structure – eschewing linearity – and theme: the romance is between a human woman and the embodied space/time continuum. Hence the lack of linearity. It’s a poignant romance and sometimes painful romance; it also confronts the bitterness of dreams lost, the confusion of family relationships, the beauty of everyday life, and the ways in which even ordinary people don’t really live life in a straight line, given the ways our memories work (Proust, madeleines, etc). This is a story that will stay with me for a long, long time.

Herc – a novel

Read courtesy of NetGalley. It’s out at the end of August.

I am bored by Hercules as a hero. But as a character in other people’s lives – as a messy, complicated, often unheroic, flawed, and realistic person – I am THERE.

The man named Heracles by his parents (who then changes his name to Hercules (which is a cute way of getting around the Greek/Roman thing) because reasons) never speaks to the reader in Herc. Instead, it’s all the people around him who tell his – and their own – story, from birth to death: father, brother, sister, nephew, cousins; wives; lovers (male and female); cousins; others met along the way. This variety showcases the different ways that people interact with the man. Some love him, while others hate him. Some continually forgive his flaws, while others are unable to.

Hercules rarely comes across well. He is strong – but he has little idea how to mitigate that strength around ordinary people, and even seems unaware of what he’s capable of. He is aware of the terrible crimes he has committed – killing his music teacher as a child, murdering his first wife, Megara, and all their children, amongst other things – and accepts that there needs to be consequences… and yet. And yet he is still seen as a hero, by those outside of his immediate circle, and indeed often by himself. And yet he seems to largely get away with being terrible. And the book does not forgive him for that.

This story dives deep into the consequences of Hercules’ actions for those around him and it is pointed, it is complex, and it is deeply thoughtful. I would read more in this style any day of the week.

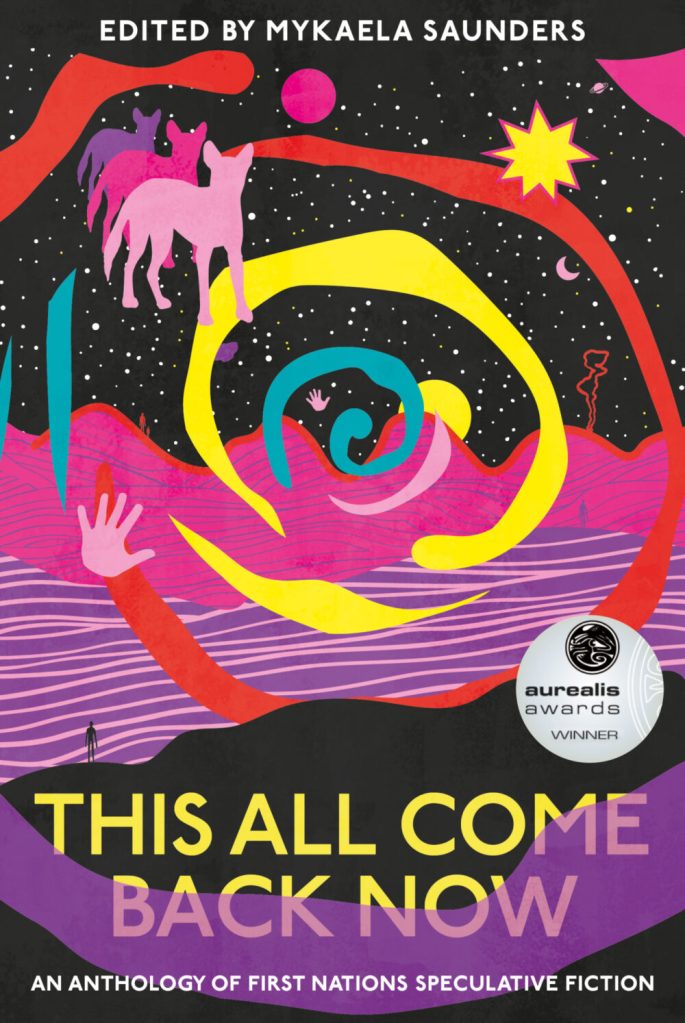

This All Come Back Now – anthology

This came out last year, and I only found out about it this year… oops; not sure how I missed it (especially given its Aurealis Award!). Available from UQP.

The first all-Indigenous Australian speculative fiction anthology! Exciting that it exists; disappointing that it took until 2022 for it to exist. Oh, Australia.

First, how glorious is that cover? It’s so vibrant and exciting.

The editor, Saunders, gives a really interesting intro to the anthology. I go back and forth on whether I read intros to anthologies; sometimes they seem like placeholders, and sometimes they give a wonderful insight into the process. This is the latter (although I did skip the last few pages, where Saunders discussed the stories themselves; I don’t like reading that until after I’ve read the stories myself. YMMV). The comparison of an anthology with a mixtape has given me all sorts of things to think about. There’s also a brief discussion of First Nations’ speculative fiction – that it exists despite what a cursory overview of the Australian scene might tell you – as well as that insight into the creative process. This is one introduction that was definitely worth reading.

The stories themselves are hugely varied; this is not a themed anthology, like Space Raccoons, but instead is tied together by the identity of the authors. That means there’s experimental narratives and straightforward linear ones; recognisably gothic, science fiction, and fantasy stories; and other stories that refuse to fit neatly into categories. As with all such anthologies, I didn’t love every story; I have limited tolerance for surrealism, as a rule – it just doesn’t work for me, but I know it does for others. Some of these stories, though, will sit with me for a long time. Karen Wyld’s “Clatter Tongue,” John Morrissey’s “Five Minutes,” Ellen van Neerven’s “Water,” just as examples – they’re profound and glorious.

I love that this anthology exists. I’m torn between hoping there can be more books like this – because featuring Indigenous perspectives and writing in a concentrated way is awesome, showcasing the variety of stories and voices – and hoping that the authors featured here will also be published in other anthologies, and magazines, and have their novels published, as well. Maybe that’s not a binary. Maybe we can have both. That would be nice.

Divinity 36, Gail Carriger

Sooo I missed this when it first came out – but it turns out I’m not too far behind the times as I read this first one (in a day…), went to look for the second one, and turns out it came out the next day (which is today, as I write). And the third comes out in October, so actually I’m doing just fine.

If you just want to buy it, or read what Carriger has to say: https://gailcarriger.com/books/d36/

So there’s many different aliens, pretty much all interacting companionably. One particular species, the Dyesi, search the galaxy for sentients who can sing or dance and then put them through rigourous training and bring them together as pantheons, because at that point those artists are gods. Yes, it’s a bit “The Voice” – or, more accurately, “Idol” where the prize is to ACTUALLY be an idol. And their performances get broadcast across the galaxy, and people literally identify as worshippers and send in votives and so on.

The focus of this series is a refugee who has a lot of trouble with ordinary emotional interactions thanks to childhood trauma. Brought together with new people and compelled to live and work with them, this is inherently a story about found family and in that it is simply lovely. There’s also, of course, music and art, and – amusingly – food and cooking.

This is a very cosy story, as should be no surprise to readers of Carriger’s work: that is, there is real and important trauma in various backgrounds but (so far) little immediate or overwhelming danger to our heroes; there’s a lot of focus on friendship and figuring out how all of that works, with a sense that obstacles can and will be overcome (not in a cheesy way). It’s a generally upbeat, inclusive, humorous, joyful story – and honestly who doesn’t need that in their lives sometimes? If you haven’t read any Carriger but you loved Legends and Lattes, I suspect this will work for you.

Desolation Road, by Ian McDonald

This book should not work.

The first few chapters are “and then this person arrived in this place that has no right to exist”. Sometimes the person or family group have some explanation about who they are or why they’re travelling; sometimes their background is incredibly vague. There are hints and vague hand-wavings at what might be coming in the future because of a particular character, and then it takes a hundred pages for anything like that to happen. There are possibly-magical occurrences, there are references that make it sound like you’ve missed the first two books in the trilogy (Our Lady of Tharsis…) and it takes FOREVER until there is something resembling a narrative.

This book absolutely works. And I don’t know why.

Well, I do: it’s because McDonald is an astonishing storyteller, and all of those things that seem wrong just become utterly intriguing and compelling. Someone who manages to make a time machine because a green person pops up at their camp as they travel across the desert? OK. Triplets who may or may not be clones; twins who split the rational and the mystical between them; someone who has an uncanny way with machines… yep, fine. I’ll read it. People are adults at 10 years old? Oh right, it’s Mars, and the Martian year is 2/3 longer again than an Earth year. So yes, actually, that’s fine.

Imagine writing this, and selling this, as one of your first books.

The Eagle and the Lion: Rome, Persia, and an Unwinnable Conflict

I read this thanks to NetGalley and the publisher, Apollo. It’s out now.

Some time back I read a book about the Mongolians, in particular at the western edges of their advance, and how those kingdoms related to what I know as the Crusader States. It completely blew my mind because I’ve read a bit about the ‘Crusades’ general era, and that book made me realise just how western-focussed my understanding had been: the invading Europeans connecting back to Europe and maybe Egypt (thanks to Saladin); maybe you’d hear about the Golden Horde occasionally. But interacting with the Mongols was HUGELY important.

This book does a similar thing for Rome. My focus has always been on the Republic and early principate, so maybe that has had an influence. But in my reading, Crassus’ loss at Carrhae is present but (at least in my hazy memory of what I’ve read), it’s almost like Parthia comes out of nowhere to inflict this defeat. Persia then looms as the Big Bad, but I think that dealing with the Germanic tribes and the Goths etc seem to take a lot more space. Even for the eastern empire, which is definitely not my forte, regaining Italy etc and fighting west and north (and internally) seems to get more attention.

And then you read a book like this. It is, of course, heavily leaning in the other direction; that’s the entire point, to start redressing some of the UNbalance that otherwise exists. These two empires could be seen as, and describe themselves as, the “two eyes” or “two lanterns” of the world (those are Persian descriptions); for basically their entire collective existence they were the two largest empires in this area (China probably rivalled them at least at some points, but although there were tenuous commercial connections, they’re really not interacting in similar spheres). It makes sense that the relationship between them, and how they navigated that relationship, should be a key part of understanding those two empires.

Goldsworthy does an excellent job of pointing out the limitations in ALL of the sources – Greco-Roman, Parthian, Persian – and clearly pointing out where things could do with a lot more clarity, but the information just doesn’t exist. Within that, he’s done a really wonderful job at illuminating a lot of the interactions between Rome and Parthia/Persia. And he also clearly points out where he’s skipping over bits for the sake of brevity, which I deeply appreciate in such a book.

It’s not the most straightforward history book of the era. It covers 700 years or so, so there’s a lot of dates, and a lot changes in this time as well – republic to principate to later empire, for Rome; Parthian to Persian; countless civil wars on both sides. A lot of leaders with the same or similar names, unfamiliar places names, and all of those things that go towards this sort of history book requiring that bit more attention. I definitely wouldn’t recommend this as My First Roman History Book! But if you’re already in the period and/or area, I think this is an excellent addition to the historiography. Very enjoyable.

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

I don’t think I’ve read The Island of Dr Moreau – or if I have, back when I thought I should read some classic SF, it was so long ago that I have no memory of it. I know the basic idea of the story: an island, where Dr Moreau has been doing human/animal hybrid experiments; I think things go badly? That’s it. I assume Moreau has a daughter in that story, but honestly maybe Moreno-Garcia just added her in? I don’t know, and actually I don’t care. I’m sure that for Wells aficionados there are lots of clever little moments in this novel. I didn’t see them, and it didn’t make a lick of difference. This story is fantastic in and of itself.

It’s set between 1871 and 1877, in what is today Mexico – specifically, Yucatán, which (I have learned) has sometimes been regarded basically as an island due to both geography and history. The story is told from alternating points of view. One is that of Carlota, the titular daughter, a young adolescent at the opening of the story. The other is Montgomery Laughton, an Englishman.

Carlota has grown up at Yaxaktun, a remote ranch, where her father has been undertaking experiments in creating human/animal hybrids. He doesn’t own it; he has been supported by Hernando Lizalde, who is expecting to get pliant workers out of the deal. Her mother is unknown, and her companions have been the hybrids themselves, along with the housekeeper Ramona. She hasn’t particularly wanted to leave, and has had a fairly good if spotty education courtesy of her father.

Montgomery has been away from England for many decades, and has spent several years now vacillating between intermittent work and considering drinking himself to death. He arrives at Yaxaktun to be the new mayordomo, although whether he’s meant to be more loyal to Moreau or Lizalde is unclear. His tragic backstory is gradually laid out although it’s never played up enough to really make him the focus of the story; for all that he shares narrator duties, Carlota is absolutely the centre of this book.

As you might expect, things do not go as Dr Moreau would like. His experiments do not produce the results he desires – and whether that’s perfecting human/animal hybrids for themselves, or somehow finding ‘cures’ to human problems, is debatable. Lizalde gets impatient at the lack of results, and brings the threat of shutting Moreau down. And then there’s Lizalde’s son, who visits and meets the lovely (and unworldly) Carlota, which has obvious consequences.

Along with the main narrative is the real-world historical situation that Moreno-Garcia sets the novel against. It’s a time when the descendants of Spanish colonists are figuring out their place in this world, when the question of who will rule and what the country will look like is pressing. It’s also of course a time of deeply consequential racism – towards the ‘Indians’, the native Mayans, as well as the not-officially-enslaved Black and other non-white people who live in the area. All of this informs how people interact, depending on how they ‘look’.

Moreno-Garcia writes a wonderful novel. The characters are vital and vibrant, the story is well paced, and the historical context makes it even more nuanced and interesting.

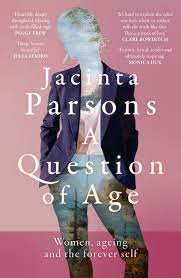

A Question of Age, Jacinta Parsons

Not the sort of book I would gravitate towards; but I heard Parsons speak at the Clunes Booktown festival this year, on a panel about ageing – which was interesting itself – and I decided it would be worth reading.

This is in no sense a self-help book, as Parsons says in the very first sentence. It’s part-memoir, in that it includes a lot about Parsons’ reflections on her own life and experiences – growing up, living as a white, disabled, woman, conversations she’s had with women about the idea of age and ageing; partly it’s philosophical reflections on the whole concept of ageing, particularly for women; and it also bring together research about what age means in medical and social contexts, the consequences of being seen as ‘old’, what menopause is and means, and many of the other issues around ageing. I should note here that it’s not just ‘life after 50’ (or 60, or 70); there’s also exploration of the experience of little girls growing up, the changes from adolescence into adulthood, and then into ‘middle age’ and ‘being older’.

It’s a book that’s likely to make many readers feel pretty angry. Not at what Parsons is suggesting (in my view), but the facts that she lays bare. About the way that girls are treated as they mature; about the way ‘old’ women are treated; at the way ‘old’ bodies are viewed, and everything around those moments. It made me realise how privileged I have been, in either not particularly experiencing (or not noticing) a lot of the sexualisation that women experience, and in not having a career that’s geared in any way around my appearance. I had a discussion recently with someone who mentioned that they didn’t feel like they were allowed to let their hair go grey, as I am – that their appearance was too important in their (corporate) work, and grey wouldn’t fit the image. I felt so, so sad that that’s what the world is enforcing. (I have always delighted in my grey streaks; it’s only partly because I am too lazy to bother with colouring it.)

Parsons is at pains to discuss what her identity means in the context of ageing – being white, and being disabled, being cis; she strives to include the experiences of queer, trans, and especially Indigenous Australian women throughout. It’s not even 300 pages in length so clearly it’s not the definitive book on the topic: a book with the same origin written by an Indigenous woman, or a collective, is going to turn out very different. Parsons is making no claim to be all-encompassing and I liked that. This is a deeply personal book, while also including a lot of science and stats and other women’s voices.

In many ways this feels like the start of a conversation. To use a meta book analogy, this isn’t the prologue – we’ve been having these conversations and there’s been research done in some important areas – but it’s around chapter 1 or 2. There’s still so much more to explore, and to examine, around ideas of ageing. And individuals need to be having these conversations, too – older women with younger, as well as peers.

Very glad I picked this up.