Black-Winged Angels

Continuing my Angela Slatter kick…

“Baba Yaga is a woman who cannot be bound. She will bear no more children, she bow to the wishes of no man; she is independent, adrift from the world and its demands. The world, in ceasing to recognise her value, has granted her a freedom unknown to maids and mothers. Only the crone may stand alone.” (p135)

“Baba Yaga is a woman who cannot be bound. She will bear no more children, she bow to the wishes of no man; she is independent, adrift from the world and its demands. The world, in ceasing to recognise her value, has granted her a freedom unknown to maids and mothers. Only the crone may stand alone.” (p135)

Angela Slatter’s exploration of the different ways women can be is one of the things I love most about her work, and it’s evident in this reprint collection. Most of the stories build on European fairytales or characters – Bluebeard, the Snow Queen, Melusine, the Little Match Girl. But the focus is different from the familiar story, because Slatter changes or explains the motivation, or centres on a different protagonist, or moves the setting and therefore the entire context… and she forces the reader to reconsider the telling of those stories, and what we can or should get out of them.

The quote above is one of my favourite parts of the whole collection, putting me immediately in mind of Ursula Le Guin’s reflections on being a ‘crone’, especially the essay “The Space Crone.” How often is old age meant to be something women should fear? And while Slatter’s Baba Yaga is by no means always happy with her status, she lives it.

This book is also a beautiful object. I have a hardback copy; the cover is black with a white cut-out illustration by Kathleen Jennings. Jennings’ artwork appears throughout the book, with each story having a dedicated picture – some quite simple, some incredibly complex. I love Jennings’ work and she beautifully complements Slatter’s ideas.

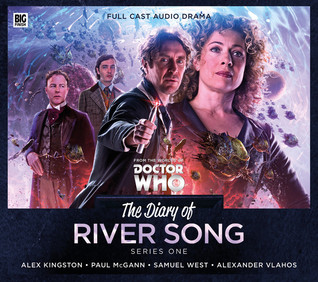

The Diary of River Song

This is my first real audio book and it was because of Tansy. I feel there are a lot of people who say things like that.

This is my first real audio book and it was because of Tansy. I feel there are a lot of people who say things like that.

Did anyone else think that the music was distinctly James Bond-ish? I got a really strong Bond vibe from it.

I have no idea whether this is standard Big Finish format, so for those not in the know: there are four 1-hour long interconnected stories. It begins with River Song having taken a position as an archeology professor (of course) who rather reluctantly gets pulled out of her office and out onto a dig in somewhere fake, Mesopotamia-ish. Bad things happen. In the next story, River is back in space, and slowly the connection to the first story is fleshed out – it’s not all fully explained until the last story. Of course the story gets bigger and more complex as the four ‘diary entries’ unfold.

Having seen the Christmas special about the husbands of River Song, I shouldn’t have been surprised by how cold River is in some of the situations presented here, but I was. I still have a somewhat childish, old fashioned view of the Doctor – that he doesn’t hurt anyone, and works for the good of everyone except maybe Daleks – and ascribe this to River as well for I-don’t-know-why. So some of the callous responses from River were… unexpected. I’m not saying I hated them, because I don’t think I did, but I was surprised.

Alex Kingston has a wonderful voice and in general did very well in this format. Most of the other actors were equally good, and I thought the production qualities were also excellent.

This has not turned me into a raving Big Finish fan, but I am glad I listened to it.

The Medusa Chronicles

This book was sent to me by the publisher at no cost.

So. This book. When I heard that Alastair Reynolds and Stephen Baxter were collaborating, I was beside myself. This is two of my great SF loves coming together. It’s Robert Plant and Jim Morrison jamming.

So. This book. When I heard that Alastair Reynolds and Stephen Baxter were collaborating, I was beside myself. This is two of my great SF loves coming together. It’s Robert Plant and Jim Morrison jamming.

At the back of my mind was the reminder that I haven’t quite adored Baxter’s latest novels, and that Reynolds’ latest novels have been quite different from his early ones too. NONETHELESS. Plant and Morrison, folks.

I really liked it… but I didn’t love it. It feels… old fashioned.

The premise: building on Arthur C Clarke’s “A Meeting with Medusa,” Baxter and Reynolds take the main character, Howard Falcon, who is a cyborg due to a serious crash years before, and extend him way into the future. This is a future where humanity is incredibly suspicious of machines and artificial intelligence, and Falcon – being the incredibly weird hybrid that he is – is often at the receiving end of that suspicion. But it also means that he’s useful as a mediator when humanity’s machines start developing consciousness, which means he’s there at the birth of that intelligence, which means he continues to be useful as an intermediary. This becomes the story of Falcon’s life, and thus the story of The Medusa Chronicles.

I did like it because I like thinking about humanity in the solar system and how that might work (this is another one where there’s looming interplanetary conflict, so apparently that’s unavoidable). I liked the whimsical attachment to the notion of ballooning as inspiration for astronauts and Jovian exploration. And I also like stories of the development of artificial intelligence and the consequences of that for humanity, although I did feel like that wasn’t explored enough here.

The novel feels a bit old-fashioned because I can’t quite fathom humanity being suspicious of machines. I assume this reflects the novels and other media I’ve been consuming – I mean yes, be suspicious, but surely only after they’ve shown that they want to kill us and use our bodies as compost? There’s also a significant level of info-dumping, which isn’t always a problem for me but can be a barrier, I know, for others. And, too, there’s a lack of significant character development. The reader gets to know Falcon almost by default, as our point of view, but most of the others – like Hope Dhoni, Falcon’s medical expert for much of his incredibly prolonged life – are almost faceless, ciphers.

There are some lovely moments and a few odd moments in the novel. The odd moments are especially where Falcon makes reference to old literature or films and wonders if anyone will get the reference – for example, to Tolkien – and yet Project Silenus is thus named because of Euripides, and in explaining the naming he doesn’t have to explain who Euripides is. I’m unconvinced about the longevity of Euripides over Tolkien (we’re talking centuries here), although I guess Euripides does have form. Some of the lovely moments are in the alternate history of NASA and thus humanity in space that Baxter and Reynolds present. Here, the threat of an asteroid completely changes the direction of the Apollo programme and has consequences for humanity going to Mars and beyond; the authors reference real astronauts, like Frank Borman and Charlie Duke, but give them a slightly different career path (and there’s no reference to ‘any similarity to real people is purely coincidental’ or however the line runs, in the fine print).

Overall this is a pretty good science fiction novel, but it’s not one of my favourites for the year.

Vigil

A number of years ago, Angela Slatter wrote “Brisneyland by Night” for Twelfth Planet Press’ anthology Sprawl. It was excellent. Vigil is that story grown-up and turned into a novel, with at least two (I believe) more stories about Verity Fassbinder scheduled.

This novel was sent to me by the publisher, as an uncorrected bound proof. Also, I had the enormous privilege of reading it in draft form, which I just can’t tell you how awesome that was. I have re-read it now partly because I have a bad memory and I knew the details had escaped me but that I loved it; partly because it’s Angela Slatter and she always withstands re-reading; and partly because it was sent as a review copy, so of course I had to. It was mostly the first two, though.

This novel was sent to me by the publisher, as an uncorrected bound proof. Also, I had the enormous privilege of reading it in draft form, which I just can’t tell you how awesome that was. I have re-read it now partly because I have a bad memory and I knew the details had escaped me but that I loved it; partly because it’s Angela Slatter and she always withstands re-reading; and partly because it was sent as a review copy, so of course I had to. It was mostly the first two, though.

Verity Fassbinder “has her feet in two worlds” – that of the Normal, where there is definitely no magic and the only things that go bump in the night are trees in the wind and possums in the bins, and that of the Weyrd. With the Weyrd, things going bump in the night may well be very old, very cranky, and very powerful. Also, weird. Her father was Weyrd; he could change shape and he was a criminal, against both Normal laws and Weyrd customs.

Verity is a wonderfully attractive heroine. She inherited strength from her father but violence is not (always) her first recourse in a dangerous situation; she’s got a pretty short temper and little patience with bureaucracy and authority; she’s a fierce friend and protector of her neighbours, single mum Mel and daughter Lizzie; she lives in a clapped-out old house in Brisbane’s suburbs. She has little interest in fashion, she’s stubborn and determined, she’s willing to compromise and admit when she’s wrong. Basically she’s human, with flaws and problems and the sorts of characteristics I would absolutely love in a friend.

Slatter’s plot is not at all straightforward. She starts with the scenario from “Brisneyland” – children going missing – and builds layer upon layer of Weyrd problems that may or may not be connected. The death of a siren (hence the cover image), the disappearance of a young man, possibly random other deaths – all of which Fassbinder must solve, with varying levels of help and hindrance from a range of friends, acquaintances, enemies and bystanders. It’s a detective story with paranormal elements, and while that’s not a unique proposition it’s the setting and the side characters (and of course Verity herself) that make this wonderful.

Brisbane is by no means a fast-paced city. Slatter has jokes about the places that do or do not get flooded; there’s jokes and having to eat out before 8.30pm; there’s a distinctly slow-paced, I guess Australian feel to the whole situation. Moving this to an American city would make it very different, and lose a lot of its charm; I hope that translates to non-Australian readers.

Verity is aided by Ziggi, driving an entirely disreputable taxi and watching her with his third eye; she’s employed, kind of, by a Weyrd ex-boyfriend, Bela, who has some hidden depths and unexpected shallows. She’s helped and hindered in sometimes equal proportions by the Norn sisters – home of an addictive caramel marshmallow log that I wonder whether Slatter has actually made – and has all-too-frequent dealings with (Normal) Detective Inspector McIntyre, who may very well be my favourite of all the side characters (sorry Ziggi) for her ‘whisky-and-cigarettes voice’ and her even lower interest in putting on a good appearance than Verity. I really hope she continues to turn up throughout the series. I would swap her for Bela any day.

Vigil is fast-paced, quirky, full of twists, and thoroughly grounded in Brisbane (even if it is a somewhat imaginary Brisbane) and the reality of immigrant Australia. I love it and I want more Verity.

Galactic Suburbia 143

In which we talk reviews and gender balance thanks to the Strange Horizons SF count, and Alisa makes books while Tansy & Alex visit the theatre! you can get us from iTunes or at Galactic Suburbia.

What’s New on the Internet?

What’s New on the Internet?

Locus Awards finalists

Shirley Jackson nominees: http://www.locusmag.com/News/2016/05/2015-shirley-jackson-awards-nominees/

Peter MacNamara Achievement Award

Strange Horizons – the 2015 SF Count

CULTURE CONSUMED

Tansy: A Sci-Fi Vision of Love from a 318 year old hologram, by Monica Byrne , Wuthering Heights by shake & stir co; Whip it, Kingston City Rollers

Alisa: Working on the release of the Tara Sharp mysteries by Marianne Delacourt (now available for pre-order) and Grant Watson’s upcoming book of film essays.

Alex: Coriolanus (all female production directed by Grant Watson for Heartstring, Melbourne’s new independent theatre); The Dark Labyrinth, Lawrence Durrell; Nemesis Games, James SA Corey; Saga vol 5; Fringe rewatch, The Katering Show

Skype number: 03 90164171 (within Australia) +613 90164171 (from overseas)

Please send feedback to us at galacticsuburbia@gmail.com, follow us on Twitter at @galacticsuburbs, check out Galactic Suburbia Podcast on Facebook, support us at Patreon and don’t forget to leave a review on iTunes if you love us!

Sourdough and Other Stories

Reading this has been a long time coming. I think I’ve owned it for a couple of years, but I’ve never quite got there before now… mostly because I knew that once I had read it, I would have read it, and then it wouldn’t be sitting there waiting to be read.

Reading this has been a long time coming. I think I’ve owned it for a couple of years, but I’ve never quite got there before now… mostly because I knew that once I had read it, I would have read it, and then it wouldn’t be sitting there waiting to be read.

Yes, sometimes my brain is weird.

TL;DR: totally, totally worth it; wonderful and strange and making me moon-eyed. It is indeed like reading those fairy tales that were deemed Not Really Fit for young children and discovering that THAT is where the good stuff is.

Almost all of the narratives in this collection are connected in some way to other stories. Sometimes this is explicit: there are a couple of families for whom generations get stories. Others are more round-about, as a passing character in one gets developed in another. This goes too, of course, for The Bitterwood Bible in which Slatter has written prequel stories, of sorts. The fact that I read Bitterwood first meant I got to see some of the places where she went back and filled in gaps, fleshed out history, made connections clearer. The upshot is that reading the stories is a bit like moving to a small town. You meet one person and then another and only a few months later do you discover that those two have History; and then over time all the rest of the connections come tumbling out – except some of them still stay hidden, teased at the edge of perception. Sourdough and the world that Slatter has created here is exactly like that.

One of the things I fiercely love about the stories here and in Bitterwood is the focus on women – and that they are so very varied. Women are daughters, mothers, lovers, wives, friends, neighbours, enemies; they are skilled, bored, frustrated, vengeful, magical, lost, bewildered, smart, sacrificial, victims and heroes. They are human.

Seriously, just read this. Come back and thank me later.

Galactic Suburbia 142!

In which the Hugo shortlist is more controversial as ever, but in the mean time we’ve been reading & watching some great things. You can get us at iTunes or at Galactic Suburbia.

MANY APOLOGIES for sound issues on this episode – we didn’t catch an accidental microphone shift which means some background noise which should have been muted were not.

What’s New on the Internet?

Hugo Shortlist

Effect of slate nominations on Hugo Shortlist at File 770.com

The Rebirth of Rapunzel winners: Margaret Eve & Kate Laidley, we hope you enjoy your book prizes!

CULTURE CONSUMED

Alex: Rebirth of Rapunzel, Kate Forsyth; The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Robert Heinlein; Defying Doomsday, Tsana Dolichva and Holly Kench; The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe, Kij Johnson

Alisa: Every Heart a Doorway; Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee; Orphan Black

Tansy: Deirdre Hall is the Devil, presented by Jodi McAlister; Teen Wolf, Downton Abbey, Doctor Horrible’s Singalong Blog, Buffy Season 1

Skype number: 03 90164171 (within Australia) +613 90164171 (from overseas)

Please send feedback to us at galacticsuburbia@gmail.com, follow us on Twitter at @galacticsuburbs, check out Galactic Suburbia Podcast on Facebook, support us at Patreon and don’t forget to leave a review on iTunes if you love us!

The Age of Genius

This book was sent to me by the publisher at no cost.

This was a really interesting book; I’m just not sure it’s entirely the book that AC Grayling thinks it is.

I adore the concept of exploring a century as a turning point; in fact for Grayling, the seventeenth century was “the epoch in the history of the human mind” (p3, his italics). Obviously other historians have disagreed, as he acknowledges, but even if there are strong arguments for other times – or even suggesting that such a claim is ridiculous – it nonetheless should make for an interesting book.

Defying Doomsday

I supported this book through its Kickstarter campaign and I am so excited that it is finally here. You can pre-order now and get your own copy on May 30.

I supported this book through its Kickstarter campaign and I am so excited that it is finally here. You can pre-order now and get your own copy on May 30.

“People with disability already live in a post-apocalyptic world,” says Robert Hoge in his Introduction to this volume. The central character of every story in this anthology has some sort of disability or chronic illness – but the point of the story is not that. The point is people getting on with surviving the apocalypse. Some do it with more grace than others; some do it with a lot more swearing and crankiness (I’m not saying that’s bad; looking at you, Jane, by KL Evangelista). Some do it almost alone, others with a few people, still others with lots of people around (which can be good and bad). The apocalypses (apocalypi?) they face are also incredibly varied, from comets hitting the planet to various climate-related problems to aliens to disease to we-have-no-idea; the settings include Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the moon, space, and indeterminate.

The first four stories give an excellent indication of what the anthology as a whole is like. Corinne Duyvis opens the anthology brilliantly with a story that includes a comet, refugees, spina bifida, food intolerances, teen stardom and adult condescension. “And The Rest of Us Wait” sets a really high bar. Next, Stephanie Gunn throws in “To Take into the Air My Quiet Breath” which combines cystic fibrosis, sisterhood, influenza, and taking desperate chances. Seanan McGuire serves up a story that somehow manages to combine being really quite cold and practical with moments of warmth; the protagonist has mild schizophrenia and autism, and not only does she have to deal with surviving a seriously bizarre problem with the rain but also one of the girls who used to tease her. No. Fair. And then Tansy Rayner Roberts does banter and romance with “Did We Break the End of the World”? Roberts somehow makes looting not seem quite so bad and THEN she does something REALLY unexpected at the end to actually explain her apocalypse which I should have seen it coming and totally did not.

So that’s the opening. A focus on teenagers, and I guess this could count as YA? But some of the protagonists in other stories are adults, so I don’t know what that does to the classification. At any rate I’d be happy to give it to mid-teens with an understanding that yes, there is some swearing, but as if that’s a problem. They should maybe skip “Spider-Silk, Strong as Steel” if arachnophobia is a problem, though.

Tsana Dolichva and Holly Kench have created an excellent anthology here. The fact that each protagonist has a disability or chronic illness isn’t quite beside the point, but it kind of is: that is, most of the time while reading the stories I wasn’t thinking “oh, poor blind/deaf/handless/whatever person!” I was thinking “I want to be with that person when doomsday comes down because they’ve got this survival thing down like nothing else.” Of course I’m not suggesting that these stories could or should have been written with able-bodied protags, or that the disabilities have been added in to be PC (which, remember, isn’t actually a bad thing). Instead what this anthology shows is that being diverse and inclusive isn’t bad for fiction. In fact it’s great for fiction. It’s an important reminder to (currently, mostly) able-bodied types like me that HELLO you are not the only people; and for people living with disability and illness this is of enormous importance, because it reminds them that (unlike what we see in many other books and films) they’re not automatically destined to die in the opening scenes of an apocalypse. They have stories and they’re important, like everybody else who’s not a straight white (able-bodied) man.

Accessing the Future

I supported this anthology through its IndieGogo campaign, because I support the idea of diverse voices in literature. I hope for the day where we can just have anthologies of science fiction that contain both able-bodied and disable-bodied characters throughout where the point is the character and their actions (this applies to gender, sexuality, colour, all the many ways in which people are diverse) but given that this is not yet that day, it’s great to see anthologies like this (and Twelfth Planet’s forthcoming Defying Doomsday) making the point that having spina bifida or being blind or autistic doesn’t prevent people from being, y’know, people. And therefore existing in the future.

I supported this anthology through its IndieGogo campaign, because I support the idea of diverse voices in literature. I hope for the day where we can just have anthologies of science fiction that contain both able-bodied and disable-bodied characters throughout where the point is the character and their actions (this applies to gender, sexuality, colour, all the many ways in which people are diverse) but given that this is not yet that day, it’s great to see anthologies like this (and Twelfth Planet’s forthcoming Defying Doomsday) making the point that having spina bifida or being blind or autistic doesn’t prevent people from being, y’know, people. And therefore existing in the future.

Well, probably. One of the interesting questions raised in a few of these stories, and indeed by people in lots of contexts, is whether/how disability will exist in the future. Pregnant friends remind me of the testing that’s done to see whether the foetus is ‘normal’; there are implants and prosthetics… and many able-bodied/ perceived ‘normal’ people would see that doing away with disability (generally in the ‘fixing’ sense but I guess more sinisterly in the ‘getting rid of’ sense) is surely a good thing? Because ‘normal’. I’m not familiar with all the discussion around this, because I don’t inherently need to be, but I know that it’s an arena that needs to be seriously discussed. I think anthologies like this help to do that.

The stories here present people dealing with different sorts of disabilities – some physical, others mental, or emotional – and with different sorts of reactions: uncaring, wanting to ‘fix’, accepting. There are very different worlds, different points in the future, and different ways of dealing with the problems before the protagonists. In most cases the protag’s disability isn’t the point; it’s part of their character, of course, and sometimes it hinders them in their negotiating with the world, but there’s no fixation on the disability itself. Continue reading →