Neverwhere

Read in a day.

Not my first Gaiman novel, despite what I initially thought; I read The Ocean at the End of the Lane a few years ago, which I also loved. I’ve had this sitting on my bedside table for about three quarters of a year, from a workmate….

Man accidentally gets involved in things beyond his ken. Weird things are happening in the part of the world that ordinary people know nothing about. People are not all they seem. British Museum features. Prose is incredibly page-turn-y. There’s not much else to say, really.

Man accidentally gets involved in things beyond his ken. Weird things are happening in the part of the world that ordinary people know nothing about. People are not all they seem. British Museum features. Prose is incredibly page-turn-y. There’s not much else to say, really.

This is a love-letter to London, in some ways, and for that reminded of China Mieville’s Kraken. There is little else of similarity, but it does amuse me to think of reading these two together as a guide to the Weird of London. It’s also, as Gaiman himself suggests, a fantastical way of pointing out the forgotten and ignored in society. There is a romantic aspect to London Below that means you maybe envy those people – but then you remember what Anaethesia experienced to get to London Below, and then what happened to her, not to mention a few others, and you realise: this is no party. London Below is a tough and unpleasant place.

The book also reminded me of Michael Scott Rohan’s Cloud Castles, Chase the Morning, and The Gates of Noon. Richard is not as unpleasant as Stephen Fisher, but there’s still the drawn-into-weird-things-against-his-will aspect, as well as the refusing-to-believe thing. I think I like Richard a bit more, though, because he’s more self-aware overall. He also reminded me of Richard Macduff, from Douglas Adams’ Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency. Again with the bewildered thing.

By the end, all I could think was how much Richard was going to be in need of Miss West’s school for those who find their way to fairyland and then have to cope with reality (in Every Heart a Doorway).

Movies and TV: 2015

Presented largely without comment: my viewing this year. Thought I had watched more movies than that, but even with short seasons, rewatching the entirety of Spooks was a pretty epic undertaking. Also the entirety of Star Wars, and the three LOTR.

Movies (new)

Of Mice and Men (National Theatre Live) * The November Man * Jupiter Ascending * Monsters University * Fast and Furious 7 * The Avengers: Age of Ultron * Mad Max: Fury Road * Woman in Gold * Veronica Mars movie * Shakespeare Retold: Macbeth * Jurassic World * Focus * Terminator: Genisys * Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation * The Martian * Hugo * Suffragette * Bridge of Spies * Spooks: The Greater Good * Sound City * Star Wars: The Force Awakens

Movies (rewatch)

Lethal Weapon * Lethal Weapon 2 * Lethal Weapon 3 * Lethal Weapon 4 * RED 2 * Notting Hill * Bend It Like Beckham * Moon * Expendables 3 * Ocean’s 11 * Jurassic Park * 2001: A Space Odyssey * Fellowship of the Ring (extended edition) * The Two Towers (extended edition) * Mad Max: Fury Road * Star Wars Ep 1: The Phantom Menace * Star Wars Ep 2: Attack of the Clones * Star Wars Ep 3: Revenge of the Sith * Star Wars Ep 4: A New Hope * The Return of the King (extended edition) * Star Wars Ep 5: The Empire Strikes Back * Star Wars Ep 6: The Return of the Jedi * The Martian * Guardians of the Galaxy * Die Hard * Elizabeth: The Golden Age

TV

Haven (season 4) * Veronica Mars (season 1) * The Newsroom (season 3) * The Dresden Files (complete series) * Warehouse 13 (season 2) * Warehouse 13 (season 3) * Veronica Mars (season 2) * House of Cards (US) (season 3) * Veronica Mars (season 3) * Carmilla * Ace of Cakes (season 1) * Orphan Black (season 3) * Marvel’s Agents of SHIELD (season 2) * Arrow (season 1) * Shakespeare Uncovered * Spooks (season 1) * Spooks (season 2) * Glitch (season 1) * Spooks (season 3) (rewatch) * Spooks (season 4) * Spooks (season 5) * Fringe (season 1) * Spooks (season 6) * Spooks (season 7) * Spooks (season 8) * Spooks (season 9) * Spooks (season 10) * Doctor Who (season 9)

Beauty Like the Night

I am amused that this is my first review for 2016. Talk about going from the sublime to the ridiculous, given the last review I wrote…

Anyway, t his book needed a serious edit.

his book needed a serious edit.

Granted I’m not the world’s most enamoured romance reader, but I do understand the enjoyment of, and possible catharsis in, reading about the anguish of do-I-love-this-person or not. But this book could probably have been cut by a quarter (ok, maybe a fifth) and it would have been a much pacier read. Still keep the angst but lose all of the boring wallowing, and repetition.

Because there was indeed an interesting enough story here, revolving around two people struggling out from under the burden of difficult parents order to make good lives for themselves. There are other characters in the background being variously nefarious or sad or mischievous, and a couple of twists that were genuine twists and made the plot itself quite pleasing. Except for the repetitious angst.

The other thing that really annoyed me was the blaming of the woman for the man’s desire. Seriously that is not ever cool. He does seem to recognise eventually that it’s not actually her fault that he feels this desire, but the language of the book doesn’t recognise that. Describing a woman as sinfully beautiful is never, ever warranted.

Also, forcing someone to kiss you is gross.

The Great Cat Massacre

I heard about this book a long time ago, probably in the context of a university history subject that was attempting to give students an overview of different ways of approaching the writing of history; it was preparatory to undertaking Honours. It was probably mentioned by Peter McPhee, discussing the idea of cultural history. At any rate, I thought of it on and off but never got around to it, and then a friend gave me a copy when culling their library of extraneous books. So I read it today. And overall, it was very good.

I heard about this book a long time ago, probably in the context of a university history subject that was attempting to give students an overview of different ways of approaching the writing of history; it was preparatory to undertaking Honours. It was probably mentioned by Peter McPhee, discussing the idea of cultural history. At any rate, I thought of it on and off but never got around to it, and then a friend gave me a copy when culling their library of extraneous books. So I read it today. And overall, it was very good.

Darnton’s approach is an anthropological one, in an attempt to understand the mentalite of sections of Old Regime French society. He doesn’t claim to be getting to the heart of 18th century French culture, nor completely understanding any one individual. Rather this is meant to be a beginning, showing a possible methodology (or road, using one of the metaphors in the book) that might allow Anglo-Saxon historians to do something the French have been doing for a while and, in his estimation, sometimes doing poorly.

There are six chapters. The first three essentially go through three different classes (DANGER WILL ROBINSON!) and look at a particular piece of culture as a way in to understanding, in some way, that person, group, and indeed the cultural milieu of France. I think I loved the first chapter the most – looking at peasants through the lens of folklore. It is the one that he describes as most ‘impressionistic’ and I get the feeling he feels almost guilty over it, and certainly worries that it appears least to rely on evidence. But it is wonderfully written, sets the context for peasant life beautifully (acknowledging the problematic nature of ‘generic peasant’), and does some really intriguing stuff in looking at variations in folkloric traditions within France and then between France and England, Italy, and Germany. He warns the reader off the idea of thinking you can completely ‘understand’ people, but suggests this as a way of better grasping how people approached their world.

The second chapter is the titular one, and is also deeply fascinating as it explores relationships between apprentices, journeymen, and masters; it also looks at the role of tormenting cats, which – whoa. The third looks at what must be a really bizarre text created by a man living in Montpellier, which seems to want to present the entire town as text and which Darnton uses to try and get at what it might have meant to be or think of oneself as bourgeois.

The second half is focussed on even more ambiguous groupings. The fourth chapter was kind of hilarious as it looks at the police reports written about ‘men of letters’ in the mid-18th century – written by a man whose job was basically to keep an eye on these producers of culture, and who makes all sorts of comments on their appearance, their literary worth, and who they’re connected to. I can’t help but imagine what a similar set of ASIO files would look like for Melbourne’s literary scene. The fifth chapter was, sadly, almost impenetrable for me: it looks at Diderot and d’Alembert and their constructing the Encyclopedie. There’s a lot of discussion of various philosophical ideas and modes of constructing knowledge and so on that I just didn’t get; Darnton presupposes a lot of understanding in his readership here that he doesn’t presuppose in knowledge of French society. Which surprised me, and disappointed me somewhat. Anyway, the last chapter is about reading Rousseau and changes in ways of reading. Darnton explicitly says not to but I can’t help but read the letters that readers of La Nouvelle Heloise as the most awesome fan letters ever; there’s a lot of weeping and sighing and offers of sex, basically. (I thought I would get to the end of the chapter feeling guilty about not wanting to read Heloise but Darnton reassures me that it’s almost unreadable to a modern audience. HOORAY.)

I had two issues with reading the book. The first, site-specific, was the opaque nature of the fifth chapter. It really bugged me. The second was the lack of women. Yes, there probably were fewer literate women at the time. Yes, digging up evidence of women’s contributions to culture can often be problematic. But the man is using folklore as real and useful evidence; I don’t think that difficulty ought to be used as an excuse here. Even in that chapter on peasants it felt like there was an emphasis on men – he uses the Perrault versions of the stories as his ‘literary’ comparisons, and of course the Grim brothers, and acknowledges that Jeanette Hassenpflug was the latter’s source, but Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy gets one mention only. And there’s no discussion, really, that women may have been involved in the transmission of stories, except in telling them to the men who wrote them down. And he does mention women as running salons when discussing the men of letters, and of being patrons, but again only in passing. I don’t know what else is out there; I would really like to have seen some discussion at least of the difficulty of finding women, perhaps as a challenge to later historians.

Overall this is a generally approachable book – not for the completely un-historical, but fun if you’re interested in the development of culture and different styles of Doing History.

Ascendant

I didn’t adore Rampant, the first book, but I was very curious to see where Peterfreund would take Astrid and her fellow unicorn-hunters. This sequel was a bit darker than the first, but overall has many of the same preoccupations: the difficulties of committing yourself to a life of killing and celibacy when you’re sixteen, the difficulties of being forced together with a bunch of girls you don’t know and have little in common with, occasionally having to deal with a crazy mother. So while I didn’t adore this one, either, I definitely don’t regret reading it.

I didn’t adore Rampant, the first book, but I was very curious to see where Peterfreund would take Astrid and her fellow unicorn-hunters. This sequel was a bit darker than the first, but overall has many of the same preoccupations: the difficulties of committing yourself to a life of killing and celibacy when you’re sixteen, the difficulties of being forced together with a bunch of girls you don’t know and have little in common with, occasionally having to deal with a crazy mother. So while I didn’t adore this one, either, I definitely don’t regret reading it.

The main surprise for me with the first book was (what felt like) its overwhelming interest in Astrid’s love life. By the end I could see why this was important – in terms of plot – and of course if Peterfreund was setting out to write a teen romance with killer unicorns then that’s totally cool; it’s just not what I had expected, which is my problem not hers. That continues into this book, naturally, with some neat (well, difficult actually) twists that meant it wasn’t simply rehashing the initial plot. Peterfreund is certainly not interested in making life easy for her characters. The romance didn’t work for me but I’m not a teenager, so maybe I’m too cynical.

I liked that Astrid got to experience life a bit outside of the Cloisters, and that she got to think through her difficulties with the whole idea of killing. There’s a nice, if simplistic, balance between Cory on the one side, all in favour of killing the lot, and Phil wanting to set up some sort of genuine conservation – and Astrid fitting between them. It did relieve me that Kill The Beast! didn’t become an overwhelming theme for the novel.

I’m surprised there’s no third book. … and I’ve just looked at Peeterfreund’s website which says that she’s hoping to write the third, Triumphant, “soon” (but I don’t know when the site was updated). I’ll probably end up reading it, although it’s not a preorder-in-a-mad-rush kinda thing.

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves

I knew nothing about this book before I started it, except that it was by Karen Joy Fowler and there had been a lot of buzz. I’m very glad about that. So if you like engaging stories with wonderful writing and a quirky narrative style (not hard to read but also not entirely linear), STOP READING THIS REVIEW and just go get a copy and read it. Seriously.

I knew nothing about this book before I started it, except that it was by Karen Joy Fowler and there had been a lot of buzz. I’m very glad about that. So if you like engaging stories with wonderful writing and a quirky narrative style (not hard to read but also not entirely linear), STOP READING THIS REVIEW and just go get a copy and read it. Seriously.

This is a simply fabulous novel and I want to thrust it into everyone’s hands. The only reason I didn’t quite read it in a day is that I was travelling, and I’m not great with reading in the car.

Books this one reminded me of: Justine Larbalestier’s LIAR (not for the content so much as the narrative style – revisiting events to give more detail, for example – and the question of truth); Jo Walton’s AMONG OTHERS (ugh, families, seriously what can you do); and, very vaguely because it’s a long time since I read it, Caroline McDonald’s SPEAKING TO MIRANDA (again, weird families).

This novel, in case it’s not obvious, is all about family. How the different members interact, how they remember things from their collective history, how they treat one another and why, the consequences of that treatment. Rosie’s family is not a happy one, and it’s clear right from the start that something difficult happened early in Rosie’s life. Fowler does an excellent job of slowly revealing bits and pieces of ‘truth’ – not so slowly as to get frustrating, but like an excellent meal of small plates: the next course arrives just at the right time, to match your appetite.

And really that’s all I want to say about the narrative, because as with LIAR this is a novel it’s best to approach utterly cold. It’s also like LIAR in its preoccupation with the idea of ‘truth’, although where for Larbalestier this was a question of deliberate truth-telling versus lying, Fowler is more interested in the question of truth and memory. Rosie acknowledges this complicating factor several time, and indeed confronts it head-on. When she’s recounting stories of her life as a five year old, from a distance of many years, she’s well aware of the problems inherent in such an undertaking. And indeed her memory of events is challenged several times by other members of her family, who provide a different perspective or more detail or entirely different versions of events – or recall events that she herself as forgotten. Rosie also muses on the perspective provided by various psychologists, often courtesy of her psychologist father, which also adds to the introspection inherent in writing a memoir.

This may make it sound like it’s a heavy, sombre book. It’s not at all. Fowler’s writing style makes it immensely engaging and page-turn-y – being required to eat dinner with my own family was quite irritating because it meant having to stop reading; seriously how unreasonable. The characters are complex and the story is tantalising and – why haven’t you read it yet?

Lament for the Afterlife

This book was sent to me by the author.

Lament for the Afterlife is not an easy book to read. Here are some times when you should not try to read it:

Lament for the Afterlife is not an easy book to read. Here are some times when you should not try to read it:

- When you want a straightforward, linear narrative.

- When you want likeable characters.

- When you don’t feel like reading about war and/or death.

- When you want to read about long-term, meaningful and loving relationships.

- When you don’t want to work at reading.

- When you just want clarity.

If you don’t fall into these categories, then you may want to approach Lament. Here are some things you need to be ready for:

- A mosaic novel. Chapters do not follow one another linearly: they are more like snapshots, or vignettes, of different points in time for different characters. Overall the story follows the experiences of Peytr, a young man conscripted for war, and almost half the story I would guess is focussed specifically on him over quite a stretch of time. But other chapters are connected to Peyt only tangentially, and some not at all.

- Unhappiness. Pretty much every character is unhappy. There’s a variety of reasons, and a variety of expressions, and a variety of consequences. Not a whole lot of resolution, though.

- Death. There’s a lot. The first half or so is firmly set within the context of war – and war that civilians actually experience; this is Sarajevo or Kabul for its inhabitants, not for the foreign soldiers. And then the second half is focussed on the aftermath of war, which isn’t much more pleasant.

- Uncertainty. Every single character experiences uncertainty, to a greater or lesser extent (will my son come home? Will I die today? Will I be safe at work?), and this is shared with the reader. The reader also gets their own share of uncertainty because Hannett leaves an enormous amount out. “Our side” are fighting the greys, and have been for ages, but… why? And who even are they? Our side also have things called wordwinds, clouds of words and fragments of thought that circle individuals’ heads… somehow? and they can be physically manipulated sometimes? Those are the big questions; there’s a lot of other tantalising questions that just don’t get addressed. I don’t require spoon-feeding from my books but I did sometimes feel a bit frustrated by the opacity of the world – partly because it made me feel like I’d missed something at some point.

- Lovely language. Hannett constructs simply beautiful sentences. Her prose is elegant and evocative and creates vibrant images – some of which are unpleasant, but they’re nonetheless powerful.

Lament for the Afterlife is set in a secondary world, but you really only know this thanks to the wordwinds; it could as easily be a post-apocalyptic world, actually, where these ‘winds have somehow developed. It’s one of those stories that feels science fictional, but aside from its setting I’m not sure I can pinpoint quite how, or why. Not that it matters – this is not a novel that is bound by generic conventions, or even playing with them. It just is. It’s not an easy novel to read; it’s not a particularly nice novel to read. It’s challenging and disturbing and sad. It’s very good.

Galactic Suburbia 134

In which we throw our remit out the window to talk about a year’s worth of non-SFF!

What’s New on the Internet

This year, the Tiptree Motherboard established the Tiptree Fellowship Program to seek out and support creators who are striving to complete new works and make their voices heard. By adding Fellows each year, this program will create a network of creators who can build connections, support each other, and find opportunities for collaboration.

First Tiptree Fellows: Walidah Imarisha and Elizabeth LaPensée.

You can donate to encourage these and other new creators – donate through PayPal — or you can mail a check to 680 66th Street, Oakland, CA 94609.

Kate Elliott on Fangirl Happy Hour

What Non-SFFH Culture Have we Consumed over the YEAR?

TV:

Alisa: The West Wing rewatch, Transparent S1 and 2, Billy and Billie S1, The Good Wife

Tansy: Leverage, Glee, Grace & Frankie, Please Like Me Season 3, Master of None

Alex: Spooks rewatch; Veronica Mars

Movies:

Alisa: Star Wars: The Force Awakens (non-spoilery discussion mostly of seating, context and spoiler-avoiding)

Tansy: Musketeers! Footloose, A League of Their Own

Alex: Suffragette; Sound City

Podcasts:

Alisa: Self publishing webinars (Mark Dawson, Nick Stephenson); Undisclosed, The SweetGeorgia Show

Tansy: The Tuesday Club

Alex: Radio Lab; new ones: Gastropod and Chat 10, Looks 3; Waleed Aly on Osher Günsberg Podcast

Comics:

Tansy: Check, Please; Dumbing of Age

Books:

Tansy: A Few Right-Thinking Men, Sulari Gentill; The Suffragette Scandal, Courtney Milan; Castles Ever After: When A Scot Ties the Knot, by Tessa Dare

Alex: Andy Goldsworthy, Enclosure; Roger Crowley, Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire; Jan Morris, The World: Life and Travel 1950-2000

Skype number: 03 90164171 (within Australia) +613 90164171 (from overseas)

Please send feedback to us at galacticsuburbia@gmail.com, follow us on Twitter at @galacticsuburbs, check out Galactic Suburbia Podcast on Facebook, support us at Patreon and don’t forget to leave a review on iTunes if you love us!

The Devil You Know

This book was provided to me by the publisher at no cost.

In this novella, KJ Parker has taken the idea of Faust and puts his own spin on it. In most versions of that story, Faust makes a deal with the devil – in the person of Mephistopheles – whereby Faust gets all of his desires seen to and the devil gets his soul after some specified period of time. Classically, Faust panics at the end of the deal; of course the irony is that all Faust has to do to get out of the deal is to ask God for forgiveness and he’d be fine.

In this novella, KJ Parker has taken the idea of Faust and puts his own spin on it. In most versions of that story, Faust makes a deal with the devil – in the person of Mephistopheles – whereby Faust gets all of his desires seen to and the devil gets his soul after some specified period of time. Classically, Faust panics at the end of the deal; of course the irony is that all Faust has to do to get out of the deal is to ask God for forgiveness and he’d be fine.

But this isn’t a review of Faust.

Saloninus is the greatest philosopher-scientist of his age, and possibly of all time. This is a secondary world, but Parker amuses himself by attributing numerous real-world achievements to Saloninus, I guess as a way of stressing how awesome Saloninus is. He makes a deal with… well, the being is never clearly identified as a demon, but that’s clearly the idea. Saloninus gets youth and twenty years of the demon being at his beck and call; he gives up his soul in return. Right from the start the demon is suspicious – why would such a man want to sell his soul for a mere twenty years? – and that’s what drives his(?) narrative throughout. Saloninus’ deal isn’t entirely clear.

One thing that got a bit annoying was the frequent switch in perspective, between the demon and the philosopher-scientist. In the version I read, an ARC to be sure, there wasn’t an easy way to tell the difference between narrators until, sometimes, a paragraph or more into the new section. Of course I got there, but there was more work involved than was necessary.

Overall, it was a fairly fun take on the idea of selling your soul.

SPOILER

The one real reservation I have is that the ending really didn’t work for me. I just wasn’t convinced by Saloninus’ motivation at all.

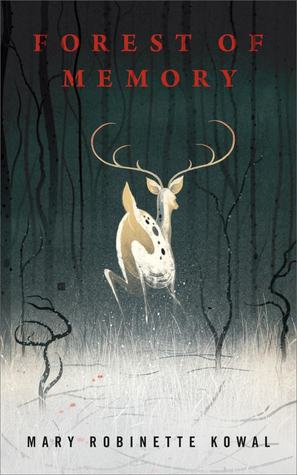

Forest of Memory

This book was provided to me by the publisher at no cost.

Mary Robinette Kowal takes the idea of memory and its fallibility as her central theme in this novella, and pairs it with the ever-fascinating ideas of narrative, and unreliable narrators, and their motivations.

Mary Robinette Kowal takes the idea of memory and its fallibility as her central theme in this novella, and pairs it with the ever-fascinating ideas of narrative, and unreliable narrators, and their motivations.

Kowal’s narrator lives in a world of permanent connection, through her intelligent system, and a world of permanent life-casting – ideas that have a strong hold on the world of science fiction writing at the moment. I was strongly reminded of Ted Chiang’s awesome “The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling.” That story is a much more rigorous exploration of the same general themes, not least because it is much longer and because it pairs those themes with ideas connecting language and meaning and memory. The two work really nicely together.

Anyway, Katya is telling a story to persons unknown who have asked for the story of three days when she was offline. (The page before the story opens has this dedication: “For Jay Lake and Ken Scholes / Who asked me to tell them a story” – which is pretty amusing in context.) She is a dealer in Authenticities, meaning old stuff with wabi-sabi (a Japanese term, she explains, of something that witnesses and records the graceful decay of life), as well as Captures on the side – that is, she sells the record of her personal experiences. The difficulty she has, of course, is that for the three days she was offline she will need to rely on her own memories, rather than asking for a replay from her i-sys. She is super aware of the possibilities here of her own unreliability, reflecting on them and looping back on herself as she considers whether or not to trust herself. It’s a wonderfully constructed piece of worry.

There’s not a whole lot of action in the story, really, and it raises enormous questions about the world in which it’s set and the reasons for why someone wants Katya’s story. I rather hope that Kowal might consider writing more stories, or a novel, set in this world and further exploring the issues raised.