The Fortunate Fall, by Cameron Reed

Read courtesy of NetGalley and the publisher, Tor Books. It’s out in August 2024 (and also was published in 1996, if you can somehow get your hands on an original copy).

This book is amazing and the fact that Tor is reprinting it and I therefore found out about is a very, very good thing.

“The whale, the traitor; the note she left me and the run-in with the Post Police; and how I felt about her and what she turned out to be – all this you know.”

As first sentences go, that’s breathtaking.

It seems from Jo Walton’s introduction to this edition that the people who read The Fortunate Fall when it first came out all loved it… but that ‘all’ was super limited, for whatever reason. And that’s just an absolute tragedy, because this book should absolutely be seen as a classic and it should get read by everyone and it should be discussed in all the conversations that are had about gender, sexuality, AI interactions, the use and purpose of the media, human/animal interactions, medical ethics… and probably a whole bunch of other issues that I missed.

It was originally published in 1996, and certainly some of the technology feels a little dated; the idea of a dryROM is amusing, and moistdisks are fascinating and gross. But honestly (as Walton points out) it also feels incredibly NOW. The main character, Maya, is a ‘camera’; when she’s broadcasting, people can tune in and see what she sees, hear what she hears – and experience her memories and reactions as well. This is mediated by a screener, who basically works to help amplify or minimise parts of the experience, as well as doing the tech work behind the scenes. For all that it’s from the very early period of the internet, this aspect feels prescient in terms of using social media, the difficult lines between personal and big-business media, and a whole host of other things that, again, are being thought about and talked about now. Not to mention the question of how much we actually know someone from their public-facing presentation.

And really? this isn’t even the most meaty part of the story. There’s the relationship between Maya and Keishi; that could have been the whole book. There’s Pavel Voskresenye and his experiences with genocide, being experimented on, surveillance – which could also have been a whole book by itself. And the whale. It’s honestly hard to talk about everything that is packed into this book: and it’s not very long! The paperback is 300 pages! How does Reed manage to fit so much in, and still make me understand everything that’s going on, and bring it all together such that I know it doesn’t need a sequel, and I know Maya in particular more than she would be happy with – and it’s only 300 pages in length??

I want to shove this into the hands of basically everyone I know. And then, like Walton says in her introduction, we can all talk about the ending.

Four Points of the Compass

Read via NetGalley and the publisher; it’s out in November 2024.

This is a really neat idea for a book. So much of the “western” world (an idea that Brotton interrogates fairly well) simply assumes that north should be the default direction at the ‘top’ of the map, and that’s how it always has been. AS someone who has deliberately put maps “upside down” and challenged students to think about why – and as someone living in Australia – book that shows exactly how and north doesn’t HAVE to be the default top, and that historically it hasn’t been, is a wonderful thing.

Brotton mingles a lot of different ways of thinking about the world in this book. There’s linguistics – the ways in which different languages’ words for the cardinal directions reflect ideas about the sun, rising and leaving, and other culturally important ideas. Like ‘Orient’: it comes from the Latin for ‘rising’, as in the sun, and came to mean ‘east’… and of course ‘oriental’ has had a long and difficult career. But in English we still orient ourselves in space. Then there’s the connections with various types of weather, in various parts of the world, something I had not considered; and of course there’s an enormous amount of association with mythology from all over the world, often privileging the east and rarely making the west somewhere to be revered. (Three out of four cardinal directions have been regarded as most important over time and space; not the west, though.) Then of course there’s history, as humans learned what was actually out there in various directions, and associated people and places with specific directions (hello, Orient). And the act of cartography itself has had an impact on how people think about direction and the appearance of the world – Mercator, obviously, and the consequences of his projection particularly on Greenland, but even how vellum (real vellum, ie made from calfskin) was shaped and therefore impacted on how things were drawn on it.

Is the book perfect? No, of course not; it’s under 200 pages, it can’t account for every culture and language. But I do think it’s done a pretty good job of NOT privileging European languages; there’s an Indigenous Australian language referenced, which is rare. (I should note that anyone who thinks they can do any sort of navigation by the ‘south polar star’ like you can with the northern one is in for a very, very rude shock.) There is some reference to South American cultures, and I think passing reference to North American ones; some African cultures are also referenced. China and some other Asian societies get more space.

This is a really good introduction to the idea of the four directions having an actual history that is worth exploring for its consequences in our language and our history. The one thing that disappointed me is that there’s no reference to Treebeard’s comment about travelling south feeling like you’re walking downhill, which seems like a missed opportunity.

Cruel Nights, Jason Nahrung

There’s a lot going on in this novella, and all of it is good.

In the first place, there’s been a lot said about the problematic nature of ancient male vampires having a thing for the young ladies. Twilight took the idea of vampires not ageing and made them students (I have no idea how old Edward was when he turned; I watched the first film from a cultural studies perspective… anyway), so the lovers didn’t LOOK that different in age which I guess was meant to make it less squicky? Nahrung approaches the whole question of age and appearance from a different angle. I won’t say his focus is unique – vampires do not tend to be my thing, so maybe it’s been done a lot (see how I avoided ‘done to death’?). But it’s something that’s obvious, once it’s pointed out: what happens for someone who doesn’t seem to age if they’re in a relationship with someone who does age? How will the partner be perceived? The way the key relationship here is approached is the reason I read this in under a day.

Second, I like to think I would have picked up the Heart inspiration based on some of the chapter titles (Magic Man, in particular), if I didn’t already know, but certainly once I got to… well. A particular scene. If you know any of the more iconic Heart songs, you can probably guess what I’m referring to. (No, I am not talking about a big-toothed fish, or any metaphor along those lines.) I’ve read a lot of books that use music in various ways, and Nahrung’s done it very nicely.

Finally, in under 150 pages Nahrung manages to evoke the experience of growing up in Seattle in the 1990s, needing to move for work and love and all the hardship that entails, family love and drama, AS WELL AS the whole vampire aspect. It’s a compact story, tightly written – I can imagine this being turned into a massive novel or duology by another author, but it doesn’t need to be: the novella perfectly conveys Charlie and Corey’s experiences.

Highly enjoyable. Get it from Brain Jar Press.

Anna Karenina Isn’t Dead (anthology)

Take examples of literary women who were, generally for stupid reasons, or otherwise treated very poorly.

Give each a new story. Either still largely within the framework of their original existence, or in a completely new story.

Bring those stories together, and create an anthology. That’s what you have here.

I actually haven’t read Anna Karenina, although I knew that she died (spoilers!). There were several other examples in the anthology where I also didn’t know the source material. Fortunately, the editor and authors have considered this, and give a short introduction to each story so that they’re all as accessible as possible. Doesn’t matter if you don’t know Madame Bovary, or the story of Lady Trieu; you can still appreciate what the authors are doing for those women who have been treated so very badly.

Wendy gets to have adventures. Pandora defies the story set for her. Miss Havisham runs a bridal boutique. Mostly, though, the women live. And thrive. They may not all end up happy, but they do at least get a real story. It’s the least they deserve. Buy it from Clan Destine Press.

Long Live Evil: Sarah Rees Brennan

I read this courtesy of NetGalley. It’s out at the end of July.

This book is for everyone who ever day-dreamed self-insert-fic, and didn’t really think through the consequences. (How distracting would I really have been to Biggles and Algie and Ginger? I don’t care about Bertie.) It’s also for those people who connect with the line “always rooting for the anti-hero” (omg turns out I like a Taylor Swift song??).

This book is amazing and wonderful and didn’t do what I expected except insofar as I was, indeed, constantly surprised by events and personalities. Surprised and delighted and absorbed and, not going to lie, a bit stressed out.

At 20, Rae is dying from cancer. Her sister keeps sharing their favourite books with her, to keep her company and to have some joy in her life. Rae didn’t pay much attention to the first book, but then things got interesting in the second. Why does that matter? Because when Rae finds herself in the world of those books, early in the timeline of the first book – in the body of a significant character – trying to figure out what’s going on, and how to fit herself in, is going to be crucial. And, well. As you can probably expect, it doesn’t entirely go to plan. Oops?

Brennan is doing A LOT here. Rae’s experience with cancer – the disease and other people’s reactions, and everything else lost because of it – reads very, very real (turns out Brennan has had very serious cancer recently; I am highly averse to reading authorial experience into books, but sometimes it’s real). So there’s that. And when Rae wakes up in her new body, she needs to figure out what she’s meant to know (and not know), and how she’s meant to act. The decision to embrace the (supposed) villainy of the character she’s inhabiting is a fascinating one with all sorts of consequences, and allows Brennan to comment on all of those Villain Tropes – and especially Lady Villain Tropes – that authors and films have loved to rely on. My particular favourites are the critiques about gravity and balance if you’ve got the boobs of the Classic Evil Seductress.

Sure, it’s got a character dying of cancer, and the fictional world she spends most of her time in is actually not a very pleasant place at all with deeply problematic characters and a dreadful social structure; people die needlessly, and the class structure is appalling. However, it’s Sarah Rees Brennan: this book is also FUN. It’s fast-paced, it loves life, it gets into tricky situations and tries to talk its way out of them, it has people trying to introduce house music where it really doesn’t belong. I consumed this novel and now I’m pining for the sequel and I don’t even know when it will be released.

Highly, highly recommended.

Embroidered Worlds anthology

I read this courtesy of NetGalley and Atthis Arts; it’s out now.

“Fantastic Fiction from Ukraine and the Diaspora”: what a brilliant anthology.

The only theme uniting this anthology is that the authors are from Ukraine, or part of its diaspora. That means that there’s a huge range of types of stories: those that are clearly rooted in folklore (even if I wasn’t familiar with the original); those that are ‘classically’ science fiction; some that are slipstream, some that slide into horror, and a few where the fantastical aspect was very subtle. Some of the stories are very much ABOUT Ukraine, as it is now and as it has been and how it might be; other stories, as you would expect, are not.

One of my favourite stories is “Big Nose and the Faun,” by Mykhailo Nazarenko, because I’m a total sucker for retellings of Roman history (Big Nose is the poet Ovid; it starts from the moment (based on the story in Plutarch, I think) of the death of Pan and just… well. The story does wonderful things with poetry and “civilisation” and nature, and I loved it.

I loved a lot of other stories here, too. There was only one story that I ended up skipping – which is pretty good for me, with such a long anthology – and that was because it was written in a style that I basically never enjoy (kind of Waiting for Godot, ish). RM Lemberg’s “Geddarien” was magic and intense and heartbreaking – set during the Holocaust, cities will sometimes dance, and for that they need musicians. Olha Brylova’s “Iron Goddess of Compassion” is set a few years in the future, and the gradual revelation of who the characters are and why they’re doing what they’re doing is some brilliant storytelling. “The Last of the Beads” by Halyna Lipatova is a story of revenge and desperation, with moments of heartbreak and others that I can only describe as “grim fascination”.

I’m enormously impressed by Attis Arts for the effort that’s gone into this – many of the stories are translated, which brings with it its own considerations and difficulties. This book is absolutely worth picking up. If you’re interested in fantasy and science fiction anthologies, this is one that you really need to read.

Ela! Ela! review

This book was sent to me at no cost by the publisher, Murdoch Books. It’s out now, RRP $39.99.

There are some excellent aspects to this cookbook, and there are some that I am not wild about.

The good: I adore a cookbook that is also part-memoir. Mittas is from Melbourne. She spent some time living and working in Turkey and Crete; each chapter of the book is about one of the places she lives – two in Turkey, then Crete, and then a section at home. Chapters start with a short narrative about Mittas’ experiences in those places, which seem to have largely been quite difficult – partly as a result of language barriers, and partly because often, what Mattis wanted wasn’t what the people she was working for could offer. These were intriguing insights, but they are more (to use a culinary metaphor) bite-sized chunks than anything like a meal.

The recipes fall into both good and not-wild-about categories. The ones I tried were mostly good! But I had some issues with the way they’re written.

- Slow-cooked lamb shoulder: very tasty; serving with tahini yoghurt, sumac onion, and yoghurt flatbread was excellent.

- Spanakopita: an excuse to make this at last! Excellent! Except… the rest of the title is “with Homemade Filo” – and, just, no. She does at least suggest using a pasta machine to roll it out – I have one, but many don’t. Why would you not have a “And if you can’t be bothered, this will use XX sheets of store-bought pastry”? Which is what I did and just made it up. The recipe also calls for “1/2 bunch silverbeet” which is… how much exactly??

- Gigantes with tomato and dill: fine. Tomato and dill is a combo I didn’t know I needed!

- Stuffed capsicum: again, fine, but some issues with the writing. It calls for 6 capsicums but says it serves 5 – ?? It also says to cover the capsicum with baking paper and foil, but that you should add more stock if required: how does one check on that?

- Galaktoboureko: not going to lie, having the excuse to finally make this Monarch Of All Desserts was worth getting the book. Kind of a cross between vanilla slice and baklava, it’s a truly glorious thing, and the recipe was fine.

So. Not my favourite cookbook of all time, but fine. Not one I’d recommend to a complete novice – there are definitely bits where there is assumed knowledge about how cooking works – but if you’re looking for an Australian-written, fairly eclectic take on Turkish and Greek food, this would work.

A Sorceress Comes to Call

Read via NetGalley. It’s out in August (sorry).

My experience of reading this went like this:

– Got the email that I was approved to read this.

– Thought, “oh, I’ll just download that so it’s ready to read.”

– Thought, “oh, I’ll just start it to see what it’s like.”

– A few hours later, thought, “oh. Now I’ve finished it and I no longer have a Kingfisher novel to look forward to.”

So that’s my tragedy. Of course, I DID get to read it in the first place, so it’s not MUCH of a tragedy.

This book is, unsurprisingly, fantastic. I adore Kingfisher’s work and this is another exemplar. Cordelia’s mother is able to literally control her body – she calls it ‘obedience’ – and as a result, even when she is in control of herself, Cordelia is always on her best behaviour. She has no other family, and no friends except for Falada, the horse, and the passing acquaintance of a neighbouring girl. She has no control over anything – doors are never to be closed in their house – and all she expects of the future is that she will marry a rich husband: so her mother has told her.

Things begin to change when her mother’s current ‘benefactor’ decides to stop seeing her, and providing for her. In order to remain in the style to which she is accustomed, Cordelia’s mother decides to find herself a rich husband, both so that she herself will be looked after and to aid in the effort to marry off Cordelia. This brings the pair into the orbit of Hester and her brother, a rich squire. Through the mother’s machinations, they come to stay at the squire’s house, and Cordelia’s mother sets about wooing the squire. Meanwhile, Hester gets to know Cordelia, and… well. As you might expect, there are ups and downs and revelations and terrible things happen and, eventually, most things turn out okay.

The writing is fast-paced and glorious. The characters are utterly believable. Apparently this is a spin on “The Goose Girl” but it’s not a tale I know very well, so I can’t tell you where Kingfisher is being particularly clever in that respect. But it makes no difference; this is a fabulous novel and Kingfisher just keeps bringing the awesome.

Lady Eve’s Last Con, Rebecca Fraimow

Read via NetGalley. It’s out in June 2024.

I was convinced that this must have been a second in a series – even when I was a third of the way through – but it turns out that the author has just set up a truly impressive amount of backstory for this one to happen. I mean, I know most good stories have their backstory, but this one REALLY felt like I was being given the “in case you don’t remember what happened in the last book” spiel.

Ruth is a con artist. Her latest con is playing Evelyn Ojukwu, shy and slightly naive debutant, with the aim of catching the eye – and hopefully a promise of marriage – from the incredibly wealthy Esteban. But she has no intention of marrying him: instead, it’s all about the money… and here’s where the backstory comes in: because Esteban done Ruth’s sister wrong, and this is a revenge game. The fact that Esteban has an awfully attractive, Don Juan-esque, half-sister is a complicating factor that Ruth hadn’t expected.

The book is set an unspecified long time in the future; humanity has spread to many different planets and systems (it took me until maybe halfway through to realise that this book was actually set on a satellite of Pluto). The details of how all of that side works are fuzzy and irrelevant. The distances involved, though, are a significant factor – there’s no super-fast communication between planets, for instance, and the lag is a critical one for both personal and business reasons, which Fraimow uses well.

I am amused by the idea that partner-catching would still be as much of a big deal in this sort of society as it’s portrayed to be in Regency England, and that the class issues are just as real. Because that’s basically what this is – it’s a Regency-like romance, with space travel and artificial gravity. It’s fluffy (that’s a positive term!) and light-hearted, with the nods to substance that show the author is quite well aware of what they’re doing, thank you very much. If you need something enjoyable, with a bit of tension and drama but the comforting knowledge that things will turn out ok, even if it’s not clear how, this book is what you need.

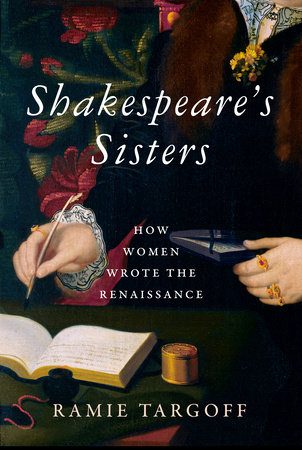

Shakespeare’s Sisters, Ramie Targoff

Read via NetGalley. It’s out now.

I’m here for pretty much any book that helps to prove Joanna Russ’ point that women have always written, and that society (men) have always tried to squash the memory of those women so that women don’t have a tradition to hold to. (See How to Suppress Women’s Writing.)

Mary Sidney, Aemilia Lanyer, Elizabeth Cary and Anne Clifford all overlapped for several decades in the late Elizabethan/ early Jacobean period in England – which, yes, means they also overlapped with Shakespeare. Hence the title, referencing Virginia Woolf’s warning that an imaginary sister of William’s, with equal talent, would have gone mad because she would not have been allowed to write. Targoff doesn’t claim it was always easy for these women to write – especially for Lanyer, the only non-aristocrat. What she does show, though, is the sheer determination of these women TO write. And they were often writing what would be classified as feminist work, too: biblical stories from a woman’s perspective, for instance. And they were also often getting themselves published – also a feminist, revolutionary move. A woman in public?? Horror!

Essentially this book is a short biography of each of the women, gneerally focusing on their education and then their writing – what they wrote, speculating on why they wrote, and how they managed to do so (finding the time, basically). There’s also an exploration of what happened to their work: some of it was published during their respective lifetimes; some of it was misattributed (another note connecting this to Russ: Mary Sidney’s work, in particular, was often attributed to her brother instead. Which is exactly one of the moves that Russ identifies in the suppression game). Some of it was lost and only came to light in the 20th century, or was only acknowledged as worthy then. Almost incidentally this is also a potted history of England in the time, because of who these women were – three of the four being aristocrats, one ending up the greatest heiress in England, and all having important family connections. You don’t need to know much about England in the period to understand what’s going on.

Targoff has written an excellent history here. There’s not TOO many names to keep track of; she has kept her sights firmly on the women as the centre of the narrative; she explains some otherwise confusing issues very neatly. Her style is a delight to read – very engaging and warm, she picks the interesting details to focus on, and basically I would not hesitate to pick up another book by her. This is an excellent introduction to four women whose work should play an important part in the history of English literature.