Curtsies and Conspiracies

This is another hugely enjoyable book from Carriger. Once again our girl Sophronia is thrown into difficulties at her alleged finishing school. This time she has a lot more to do with the supernatural element of her world, especially the vampires. Of course there’s a lot of discussion of dresses and fashion and hats and reticules; she must figure out how to carry a knife without it being obvious, she must learn to bat her eyelids effectively, and how best to carry the implements required of a young lady in her position. I’m still surprised by how enjoyable I find yet another school focused book.

This is another hugely enjoyable book from Carriger. Once again our girl Sophronia is thrown into difficulties at her alleged finishing school. This time she has a lot more to do with the supernatural element of her world, especially the vampires. Of course there’s a lot of discussion of dresses and fashion and hats and reticules; she must figure out how to carry a knife without it being obvious, she must learn to bat her eyelids effectively, and how best to carry the implements required of a young lady in her position. I’m still surprised by how enjoyable I find yet another school focused book.

Most of this book is spent on the dirigible of Miss Geraldine’s finishing school. Some time is spent in classes, learning about domestic economy, poisoning, fainting and how to properly address vampires. But for Sophronia, much of her time is spent on the outside of the dirigible – climbing – as well as with the sooties down below and the dressing-as-a-boy Vieve. Interestingly the plot follows on from Etiquette and Espionage, in that the MacGuffin here is the same. Of course this time it’s not so much about finding the prototype as it is about figuring out what it can do, how it will do it, and who will control it. There’s a surprising amount of politics for a book that seems at least on the outside as being solely can send with fashion. I guess that’s kind of the point; that the two don’t have to be mutually exclusive and anyone who is thinks they are is likely to underestimates graduates of Miss Geraldine’s finishing school.

One of the big differences in this book compared to the original is that there’s a lot more boys. I’m not really sure what I think about this; on the one hand it’s obviously an important skill for girls like Sophronia and Dimity to learn – that is, how to deal with difficult yet handsome young man. And of course reappearing in this book is Soap, certainly one of my favorite characters although somewhat problematic given that he’s black and his nickname is Soap. On the other hand I really enjoyed the almost exclusively female cast of the first book; the fact that boys were not necessary for the book to proceed, the fact that the girls were perfectly capable of getting themselves into and out of scrapes generally without any male assistance (or hindrance) at all. While some of the ways that Sophronia dealt with her would-be suitors was entertaining, I did find myself enjoying the sections of the plot that solely involves the girls generally more enjoyable.

I continue to be fascinated by the development of this world that Carriger initially developed for the Alexia books. And of course I remain desperately keen to find out how this series will intersect with the earlier one. One of those intersections is quite obvious but I have no doubts that Carriger will provide some further surprises in the rest of the series.

The Farthest Shore

For a book written for children – perhaps a young adult audience – this sure is a bleak book. It’s also a deeply philosophical book, as well as having a great deal of adventure and learning about life. It’s the most Tao book of Le Guin’s Earthsea series. It’s an odd book to come after The Tombs of Atuan, as that was after A Wizard of Earthsea; the pace is so different. I think Wizard must come first but for these two the order is irrelevant. It’s also back to bring an almost exclusively male narrative.

For a book written for children – perhaps a young adult audience – this sure is a bleak book. It’s also a deeply philosophical book, as well as having a great deal of adventure and learning about life. It’s the most Tao book of Le Guin’s Earthsea series. It’s an odd book to come after The Tombs of Atuan, as that was after A Wizard of Earthsea; the pace is so different. I think Wizard must come first but for these two the order is irrelevant. It’s also back to bring an almost exclusively male narrative.

I know young adult books are often bleak; we have a rash of dystopian novels to prove that. But in roughly 170 pages Le Guin explores the consequences of rushing off after life at the expense of losing life; of fearing death so much that you give up on life; and the sheer loss of hope, and what that might do to society. Somehow the fact that Le Guin does it so quickly makes it seem more bleak. Like the first book

this book is about one quest, one search for one man. Instead of taking an entire trilogy, with lots of disappointments and setbacks and newfound friends, Le Guin has Sparrowhawk, now with a new young friend, simply track that man down. Of course it’s not really a case of doing anything “simply”. There are set backs. The book does show us more of Earthsea and its environs, and we meet a variety of different people; but everything is designed to assist in the one quest. And as I said before, it is only 170 pages. Le Guin’s words are evocative and precise. There is glorious description, but it doesn’t go on forever. Characters are swiftly sketched. Swiftly, and brilliantly. The story is as driven towards its conclusion as Sparrowhawk is towards his.

We always knew that Sparrowhawk would turn out to be the archmage. We were told that in the first book. And here he is, Archmage for five years, now being confronted by something strange going on to the south and to the west of the Inner Lands. Unsurprisingly Sparrowhawk is feeling confined by the walls and the tasks and the requirements of being archmage. It’s not clear how long after the events of the previous books this is happening. And in some ways, as the book reminds us, it doesn’t really matter. Sparrowhawk has had a long and distinguished and occasionally difficult career as a sorcerer. Many of those deeds get recorded in the songs made about him at some point in the future. This is another one to add to his long list. Of course, he is not the only – and perhaps not even the main – protagonist of this book. He is joined by a young prince, perhaps just slightly older than Sparrowhawk himself was in A Wizard of Earthsea. It’s therefore a coming-of-age story for young Arren, as that book was for Sparrowhawk. Not that Sparrowhawk doesn’t have a lot to learn: about himself and about his world and about what must be done.

Life and honour and death and hope and love and fear. What more could an author hope to explore?

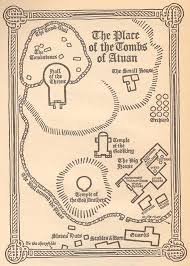

The Tombs of Atuan

While there’s a similar feel in the language – sparse and intense – this is a very different book from A Wizard of Earthsea. It’s bound to just one place; it’s focussed on a girl. The struggle for identity is similar but Tenar/Arha has less agency than Ged, which is understandable given her very different situation. There’s very little magic.

I might love this more than A Wizard of Earthsea.

It’s so… peculiar. It’s simple enough to find parallel stories – mythic ones, modern ones – for Ged, since he is basically a young man finding his purpose and his way in the world. It’s a coming of age story, if not ‘simply’. For Arha though… the situation is different. It’s still a coming of age story; it is about Arha finding her purpose and place and understanding the world. But it’s focussed so tightly on the Place that it feels completely different. Is there a difference in a girl coming of age and a boy? Certainly in terms of myth there is, and Le Guin is, I think, interested in writing Myth in these stories. In fact she makes some quite obvious comments about mythology; we know, in A Wizard of Earthsea, that Ged goes on to become something great (how’s that for foreshadowing and reassurance?), and that there are stories about him. Arha is basically living a myth.

It’s so… peculiar. It’s simple enough to find parallel stories – mythic ones, modern ones – for Ged, since he is basically a young man finding his purpose and his way in the world. It’s a coming of age story, if not ‘simply’. For Arha though… the situation is different. It’s still a coming of age story; it is about Arha finding her purpose and place and understanding the world. But it’s focussed so tightly on the Place that it feels completely different. Is there a difference in a girl coming of age and a boy? Certainly in terms of myth there is, and Le Guin is, I think, interested in writing Myth in these stories. In fact she makes some quite obvious comments about mythology; we know, in A Wizard of Earthsea, that Ged goes on to become something great (how’s that for foreshadowing and reassurance?), and that there are stories about him. Arha is basically living a myth.

I’m fascinated by Arha. I love Le Guin’s exploration of the fact that she is a wilful young girl – and who wouldn’t be, being told that they are the First Priestess reborn, and basically untouchable by any of the people around her? When you are so set apart from those around you, it makes sense that you would become aloof and indifferent. And yet Arha is also vulnerable; she fears Kossil, the High Priestess of the Godking, but also relies on her. She is overcome by her fear of the dark, when first taken to the Undertomb, and then overcomes the fear in turn. I can imagine that, left to her own devices, she would have become quite formidable… within the restricted space she can access.

This is a claustrophobic novel. Where A Wizard introduces the reader to many parts of Earthsea, this one only really allows us to see one remote, nearly forgotten, temple complex. And yet the plot itself doesn’t feel that constrained, perhaps because – for most of it – Arha doesn’t notice it. It’s a testament to Le Guin that she makes such a small area so intensely powerful and important.

I had forgotten how much I love this book. In fact, perhaps I didn’t used to love it so much, and this is a reflection of greater maturity… I guess I read this in early high school, and I don’t think since. Onwards to more Le Guin!

A Wizard of Earthsea

I first read this… I don’t remember when. I think I was at primary school. And I’m not sure whether I’ve read it since, but it had a very big impact on me. I could still remember a lot of the little details, and my fierce appreciation, fear, and sympathy for Ged.

A friend who read this as an adult just couldn’t cope with Le Guin. It made me think that perhaps Le Guin is like a really amazing pencil sketch, where someone like Martin or other such epic writers are oil painters. Le Guin doesn’t waste words; she doesn’t give lush, page-long descriptions. But this isn’t a detraction; she’s evocative and masterful in her language, and she tells a grand tale in (in my copy) well under 200 pages. That’s not something to be frowned upon! … but it could be something that people with tastes shaped by more modern fantasy writers find hard to cope with. And that’s fine; it’s just a different tastes thing.

A friend who read this as an adult just couldn’t cope with Le Guin. It made me think that perhaps Le Guin is like a really amazing pencil sketch, where someone like Martin or other such epic writers are oil painters. Le Guin doesn’t waste words; she doesn’t give lush, page-long descriptions. But this isn’t a detraction; she’s evocative and masterful in her language, and she tells a grand tale in (in my copy) well under 200 pages. That’s not something to be frowned upon! … but it could be something that people with tastes shaped by more modern fantasy writers find hard to cope with. And that’s fine; it’s just a different tastes thing.

I love that Le Guin starts with Ged as a wild young thing. I read somewhere that when she was commissioned to write a children’s book she looked at the wizards she knew and they were all old men (she’s a big LOTR fan), and she thought: how did they get there? So forty years before Rowling, she wrote of a wizard school. And Ged is nothing like Harry.

The friendships are wonderfully understated but nonetheless feel real; the dangers are never dwelt on in horrific detail but are nevertheless palpable. Ged’s efforts, his fears, his determination – all come through. Perhaps this is why I appreciate Rosaleen Love: her sparse language is a lot like Le Guin’s, and they both manage to capture a great deal in few words.

I also love that the only white-skinned people in this story are the invading barbarians, who only occupy a few pages.

Chimes

This book was provided by the publisher.

I’m a little conflicted by this book, and I know I won’t write a review that does it, or that ambiguity, justice.

On the one hand this is a book of gorgeous prose. It’s lyrical (heh) and it’s evocative, setting up beautiful word-pictures. This is a world where although sight still exists, hearing has become far more important for many people – an inversion of today? There’s talk of whistling directions, of using tunes as advertisements and as aides memoire, and then there’s Chimes. Chimes is music that plays at Matins and Vespers, and no matter where you are (well, within the small geographic scope of the novel) you have to pay attention. It’s fairly fast-paced; Smaill does a good job of showing the dystopian nature of the world without a whole lot of detail; I found the conclusion satisfyingly dramatic.

On the one hand this is a book of gorgeous prose. It’s lyrical (heh) and it’s evocative, setting up beautiful word-pictures. This is a world where although sight still exists, hearing has become far more important for many people – an inversion of today? There’s talk of whistling directions, of using tunes as advertisements and as aides memoire, and then there’s Chimes. Chimes is music that plays at Matins and Vespers, and no matter where you are (well, within the small geographic scope of the novel) you have to pay attention. It’s fairly fast-paced; Smaill does a good job of showing the dystopian nature of the world without a whole lot of detail; I found the conclusion satisfyingly dramatic.

On the other hand… there are enormous questions that are never answered about how ‘the world’ got like this (there’s hints but that’s all), whether the entire world is like this or just some area around London, and there are a few plot holes here and there that are glanced over. What I can’t figure out is whether these things matter or not. On balance, I think I can live with those problems, and it’s mostly because of the beauty of the language. If this were a more pedestrian novel I would have more problems with it. The one problem with the language is the use of musical terms. No one does anything quickly or slowly; it’s all piano, lento, tacet… and I don’t even know if some of the words were invented. I have zero musical training so there were times where I was confused about whether we were rushing or going stealthy. Still, I coped. I was a bit sad at about the halfway mark that the novel was so boy-heavy (I hadn’t read the blurb so I actually thought the narrator was a girl, at the start), but by the end I was a bit more content with the gender choices overall.

The novel is written in the first person and in present tense; I feel like I haven’t read a whole lot of present-tense stuff recently, so that was intriguing. Our protag is off to London with a mission from his dying mother, but he has to hurry because he’ll lose his memory of what he’s doing pretty soon. Because everyone does. This is a world where people are just about living Fifty First Dates. They keep ‘bodymemory’ – usually – so they remember how to eat, how to do the manual parts of their job, and so on; and maybe ‘objectmemory’ can help with some specific events… but unless relationships, for instance, are renewed every day, pretty soon those people are gone from your mind. Because of Chimes. The music you can’t not hear.

Simon, of course, is a bit special – he’s got a slightly better memory – and while the whole You’re Special thing might be a bit old, that’s because it’s such a good way of making change happen in a difficult world. Anyway, Simon starts finding out more about his world, thanks to a new friend, and things progress from there. I liked Simon, overall, as a voice for showing the world, but really we don’t find out that much about him – I think as a factor of the first-person narration. That’s not necessarily a problem; you’re enough in his head on a day-by-day basis that I, at least, certainly cared what happened.

The musical aspect is original, at least in my reading experience, and the prose is a delight. For a debut novel I’m even more impressed – and not surprised to discover that Smaill is both a classically trained violinist and a published poet. I hope she gets to publish more books, and I hope this features on the Sir Julius Vogel ballot next year (she’s a Kiwi). You can get it from Fishpond.

The Great Ship

I had read a few Great Ship stories before (two of which are in here), so I was really excited about getting a collection that has almost all of them, in some sort of order.

I had read a few Great Ship stories before (two of which are in here), so I was really excited about getting a collection that has almost all of them, in some sort of order.

Let me get the annoying thing out of the way first. This collection was collated by Reed himself, as far as I can tell, with a bit of additional material to bridge the stories (and adding to “the resident confusion” apparently), and some stories altered as well to better fit with the others. There are a lot of typos, and a number of problems that I would have expected proofreading to catch. This didn’t detract from my overall enjoyment of the stories, but I found it really quite frustrating. Also, rather than having headers that give the name of each story, the header is a number: so it might have “5 95” at the top of the page, which tells you you’re on p95 overall and section 5 on whichever story is on that page. But it doesn’t tell me which story! Argh. Anyway.

There’s no point in talking about every story; that would be tiresome. I realised as I read the last story that the collection as a whole rather put me in mind of Christopher Priest’s The Islanders. They have nothing in common in terms of themes or characters or setting, but there is a certain way in which their methods of connecting disparate elements feels similar. In Priest’s work, the same character might turn up on several different islands and you learn about them a little more. Here, there are a couple of characters who recur in a big way (Quee Lee especially, and Perri), and several others who appear intermittently. Additionally, the Great Ship is so very big that each story is set in a different place – and sometimes not even on the Great Ship – so that, like the Dream Archipelago for Priest, it’s the same place but very different.

The Great Ship is just that: a spaceship that is at one time described as being the size of Uranus. And there’s very few who live on the surface – which would be big, but not that impressive: rather, the entire innards of the Ship is honeycombed with a vast array of habitats, meaning that the Ship can support countless billions. For whatever reason it was launched into the universe, travelling along, and then humanity managed to board and claim it. But it’s not just a human ship; any species, as long as they’ve got the cash to pay their way, can come along for the ride. And what a ride: they’re doing the ultimate Grand Tour, around the Milky Way.

All of the stories are entirely standalone. There is no reason to read this collection in the order it’s presented. Except that Reed claims to have it in some sort of chronological order (and certainly the two bookending stories feel like a beginning and an end), and there is something very satisfying about feeling like you’re progressing through the history of the Great Ship and its passengers. And everyone is a passenger, whether they’re paying or working their way. I like that there are stories about rich folks as well as people who work on the ship; it wasn’t quite balanced, but it’s better than simply seeing the idle wealthy. There are stories of action and adventure; stories about relationships, and solitude, and time; there is death and birth and just getting on with things.

One of the odd things about these stories is the issue of time. Pretty much everyone on the Ship is functionally immortal. No diseases, no ageing; you get hurt but as long as your brain is intact it doesn’t even matter if you die. So ideas like your husband being away for a year (or ten), or a journey taking thirty years, or having to hide for centuries… those words, those time-concepts, are basically irrelevant. I didn’t end up with much of a sense of grandeur or the epic sweep of time because the numbers are so big that my mind just rebelled and basically say those as weeks, perhaps months. Which doesn’t make the stories any less interesting but perhaps is not the response Reed is hoping for.

I do intend to read the Great Ship novels… but I might go read something on a slightly smaller scale first…

Tam Lin

I was in my mid 30s when I finally watched The Breakfast Club. I rally enjoyed it but I’m glad I didn’t watch it when I was at high school; school was already something of a disappointment.

I read Tam Lin for the first time this year, 15 years after finishing my undergrad studies – yes, with a BA. I am really glad that I didn’t read this before or during my studies. I thoroughly enjoyed university, but there was very little spontaneous Shakespeare and Milton and Keats quoting going on.

I read Tam Lin for the first time this year, 15 years after finishing my undergrad studies – yes, with a BA. I am really glad that I didn’t read this before or during my studies. I thoroughly enjoyed university, but there was very little spontaneous Shakespeare and Milton and Keats quoting going on.

I’ve heard about this on and off over the years; Tansy is a huge fan. I didn’t really have any idea of what to expect – I don’t know the ballad on which it is based, and although I knew there was some Fae element I think I was expecting a kind of Tom’s Midnight Garden experience, going in and out of fairyland? Or something. So it wasn’t what I expected, but mostly in a good way.

Spoilers ahead, if you’re like me and not up on your faery-tinged-undergrad-learning love story!

(That is, it’s a love story to undergrad learning. Although there are love stories in the novel as well.)

Like I said, I was expecting the fairy stuff a lot earlier than it actually turned up. To the point where I got to wondering that because the university experience was so exquisite, was that actually the fairy land? And Janet would eventually wake up? Or something? It was amusing to note the similarities in Janet’s experience of college and my own, as well as the differences, some of which are temporal (25 years different), many I suspect are geographical (US expectations of a ‘liberal arts degree’ are very different from Australian ones… doing physical education? As a compulsory unit??… plus I will never, ever understand the necessity of rooming at college – and I lived in residence for two years), and most of them are of course fiction v reality. With the hindsight of my mid-30s, I enjoyed this fantastical take on college, while acknowledging just how unreal it was. I really liked the discussions Janet and co had around poetry and theatre and what to major in – those discussions can be, and sometimes were, glorious – as well as the fact that Dean includes in-class stuff, with good lecturers and bad. It did make me a little sentimental for my own experience, which I am definitely seeing with a rosy tinge these days. I was also interested in the fact that, published in 1991, it was set 20 years prior. By the end this decision made sense – the stuff about pregnancy and being on the pill would presumably have been a much more raw and radical issue in the early 70s, socially speaking, than in the 90s. Plus I suspect that many people look back on the early 70s rather romantically, as a time of liberation and so on.

Obviously there are hints that things are A Bit Odd from quite early on: the stories about Classics majors (heh; I only have a minor in it), the odd temporal questions and connections, the intensity of some of the relationships…. I admit that I cracked about 2/3 of the way through and looked up some of the names… and yes, there were a couple of them, in the roll of Shakespeare’s company. So that gave me a bit of a clue of what was going on. Like a few reviewers on Goodreads I found the denouement a little bit rushed – in, what, the last 40 pages? it’s revealed what Medeous actually is, and is doing. But… ultimately, for me, the faery aspect isn’t what the book is actually about. But still, I liked the triumphal-tinged-with-doom ending – although a sequel would be extremely ill-advised. I hadn’t picked up the Thomas Lane/Tam Lin connection! Oops.

I liked Janet. Yes, she’s a bit spoiled, and she would almost certainly have driven me a bit mad if I’d met here at 18 – she’s so confident in her own knowledge. But I admired that, too, and the fact that she struggles and overcomes. I liked that her friendships weren’t always easy and that she acknowledged the necessity of working on them – even if she didn’t always do it well; I’m a nerd so I definitely liked her dedication (mostly) to learning!

I can imagine reading this again. I would love to recommend it to young friends, but I don’t think that in good conscience I can – not until they’ve finished at university.

Orphans of Chaos (John C Wright)

Yeh nah.

I am not into bondage; I don’t especially like reading about it. I understand that other people do, and that’s cool; I really don’t care. Whether I will keep reading a book that has bondage stuff in it depends on whether the plot and the characters warrant it, and how uncomfortable those scenes make me.

Enough of a prelude?

This started out well enough. Five apparent orphans in a boarding school where they are the only students; odd goings-on, and at least one student convinced that they’re not actually on Earth (why? who knows). The student interactions were usually entertaining enough and the discomfort level wasn’t too high, for the first half or so. I was quite looking forward to finding out what odd thing was going on and whether the kids would have powers.

This started out well enough. Five apparent orphans in a boarding school where they are the only students; odd goings-on, and at least one student convinced that they’re not actually on Earth (why? who knows). The student interactions were usually entertaining enough and the discomfort level wasn’t too high, for the first half or so. I was quite looking forward to finding out what odd thing was going on and whether the kids would have powers.

Then the governors etc of the school turned up and it was Lady Cyprian (although I was confused by her because I really thought they were saying her husband was the Unseen One, thus Hades, so I thought she was Persephone even though her attitude and name didn’t fit… nope, turns out I misunderstood and her husband was indeed Hephaestus). Some of the ways these characters were referred to was confusing, but then alternately transparent, so I got a bit impatient with the ‘are you trying to disguise their Greek god-ness or not’ – and then there were references to their Roman names but also that they were Greek gods – and I started to get doubtful.

Then the two girls dress up as very provocative maids in order to distract a cranky gardener called Grendel… which I can maybe come at because in theory they’re 16 but in reality there’s something weird about their ages… but THEN the three boys ‘vote’ on making them stay in those outfits, and the girls don’t get to ignore them.

So: yeh nah. I have no idea where I got this from; it’s been sitting on my iPad for ages, and I’ve never got around to reading it. Now I don’t have to finish it or worry about the sequels.

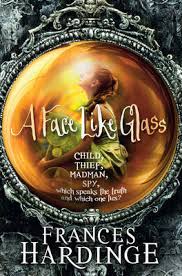

A Face like Glass

There is an exquisite agony in expectation.

A few years ago I read Gwyneth Jones’ Bold as Love sequence. I owned all of the books but I read them over almost a year… because it was kind of almost fun to wait, even though I had no need; and because I didn’t want the ride to be over.

Last year I did the same with Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series (which still isn’t finished because I haven’t got around to finding the last two), and Sarah Monette’s Mirador.

I had Frances Hardinge’s A Face Like Glass sitting on my desk for a full week, waiting to be read. It’s not exactly a year, but the principle is the same: knowing that I had it there waiting to read was incredibly exciting; knowing that as soon as I started reading it would soon be over was excruciating. Because oh my Hardinge is a glorious, glorious author.

I had Frances Hardinge’s A Face Like Glass sitting on my desk for a full week, waiting to be read. It’s not exactly a year, but the principle is the same: knowing that I had it there waiting to read was incredibly exciting; knowing that as soon as I started reading it would soon be over was excruciating. Because oh my Hardinge is a glorious, glorious author.

And now I’ve read it and it was as I expected – which is to say even better than I expected – but now I am FINISHED and I am BEREFT.

A curmudgeonly cheesemonger is so antisocial he just lives in the tunnels with his cheeses (no ordinary cheese, it should be said, but cheese that can make you see visions and hear songs and maybe spit acid at you. TRUE Cheese). One day he finds a girl in a vat of whey… and her face: well, he makes her wear a mask.

Now, you might be thinking this guy is a bit odd. And he is. But the society he’s turned his back on is that of Caverna; they all live underground. And the other thing that’s different about them is that as babies, they don’t learn facial expressions. At all. Babies, toddlers, even adults if you’ve got the money, have to learn Faces: initially from family, and then from Facesmiths. Yes, this is as weird as it sounds… and it ends up being a really interesting reflection on class issues. Once you’re an adult, it costs a lot to learn new and interesting Faces; so of course, the poor don’t. And can’t. Does that mean they don’t have the emotions that require such a range of emotions?

Indeed, what does it mean to feel an emotion if you can’t express emotion via your features? Hardinge doesn’t pretend to have all the answers, but she makes a compelling, swoon-worthy novel from the issue.

It’s not all cheese and frowns, though. There’s also intrigue, friendship, losing your way, kleptomancy (my new favouritest way of telling the future), True Wine and Cartographers whose words can make you go crazy. There’s recognising your own emotions as well as others’, figuring out who to trust and how to trust yourself, and the willingness to Go With The Crazy.

And then there’s the glory that is Hardinge’s prose. Her words don’t just flow; sometimes they trickle and sometimes they gush but they always worm into your brain and create stunning pictures and magnificent juxtapositions. I’m pretty sure I could read Hardinge’s shopping list and it would be a work of lyrical beauty.

Get it from Fishpond. If you have never read a single Hardinge, read this one… and then read the rest….

The Female Factory

It took me a while to read this one. I read “Vox” and “Baggage” and then had to have a metaphorical lie down for a week, to catch my breath, then read the last two stories.

Seriously. These two ladies. THEY DO THINGS TO MY BRAIN.

Seriously. These two ladies. THEY DO THINGS TO MY BRAIN.

The no-spoilers version is: this collection is about being a woman, and children, and social expectations, and identity.

Now go read it. No, seriously.

Spoiler-filled version:

“Vox” is incredibly chilling, probably the most of the four stories, and on two laters. Kate’s obsession with the voices of inanimate objects is kooky but not that strange; her despair at not being able to have children is a familiar one. The further despair at having to choose just one child cuts deep… but the fact of what happens to the children she doesn’t choose? I had to reread the sections about the electronics’ voices a couple of time to check whether HannSlatt really had gone there. And yes, they really really had. Plus, Kate’s attitude towards her existing child… says some hard things about maternity. Confronting, in fact.

“Baggage” is a nasty little piece of baggage, with a central character lacking pretty much any redeeming personality features and a quite unpleasant world for her to feature in. Her particular ‘gift’ is never clearly explained, which I liked, given how supremely weird it is. There are definite overtones of The Handmaid’s Tale, although obviously it’s very different, and also perhaps Children of Men? Once again with maternity, although I imagine Kate would be horrified by Robyn’s attitude towards her own fertility, and the cubs she produces.

I loved “All the Other Revivals.” Well, I… hmm. Maybe I didn’t love all of them, but it’s not to say I didn’t love the others…. Oh anyway, it was interesting to come across a male voice, after the first two strong female voices. Not that Baron would see himself as a particularly strong <i>male</i> voice, I suspect. Once again the central conceit – the car in the billabong – isn’t explained at all; it just does what it does. And Baron is who he is, whoever that is – and will be. Once again the nature of motherhood is really strong here, although in a very different way from the first two stories; this time it’s a matter of absence, and one that’s never explained. I guess the billabong can be seen as a sort of mother, too, now that I think about it.

Finally, the titular “Female Factory” – named for a real place, I discover, in Tasmania OH MY BRAIN again. Again with the absence of motherhood (so it was a wise thing to do, to read the first two together and then the second two) – this time the story is from the perspective of young children – orphans no less – influenced by daring medical science in the early nineteenth century and their proximity to two cadaver-obsessed adults. Somehow this story, while creepy, felt perhaps the most comfortable of the lot; perhaps because its ideas are a bit familiar? Which isn’t to say it’s not an excellent story, which it is.

Overall this is an excellent #11 for the Twelve Planets, and once again Lisa Hannett and Angela Slatter have well broken me. You can get it from Twelfth Planet Press.