The Lathe of Heaven

And so my le Guin adventure continues…

Sooo… not my favourite le Guin. Which is sad, which is itself silly, since I half expect every new le Guin to become my new favourite!

Sooo… not my favourite le Guin. Which is sad, which is itself silly, since I half expect every new le Guin to become my new favourite!

The premise here is that George, a remarkably ordinary man, has the ability to have what he terms effective dreams: dreams that alter reality. He doesn’t always dream effectively, but when he does he can’t control it. And it’s driving him mad, because he doesn’t want to have this ability. Thus, drugs, and then therapy. However, that’s when things go even less as George would want them to, because his psychiatrist Haber discovers the ability and… well. ‘Manipulation’ has such ominous overtones, but it’s appropriate here.

Objectively, there is little about this book that ought to work, in some senses. For a start, George Orr is a nobody. He doesn’t want to be a villain or a hero. In fact, there are several long sections of the book where the incredible normal-ness, average-ness, and boring-ness of George are analysed in depth, with some interesting discussion about whether his being so very very average is actually quite amazing. I really like George’s normality, and I can imagine that choosing to put this amazing ability into the hands of Mr Boring was actually quite a radical choice for le Guin (it also made me think of Deb Biancott’s Bad Power set of stories, where people get powers without having any desire to have them). Haber is another sort of character altogether, and a deeply unpleasant one at that. But still we don’t get very much insight into Haber – not whether his actions are motivated by greed or misguided altruism or what. We only see him through George, and George is a fairly ignorant observer.

Then there’s the narrative. There isn’t really very much plot, as such, for the simple reason that the world keeps changing. There can’t be much continuity, even in George’s own life, when he keeps changing fundamental aspects of the world itself. And this is disturbing and uncomfortable and a rather confronting narrative device. Of course, part of the point I suppose is to demonstrate that ‘changing the world’ isn’t as easy as it sounds; Haber thinks it will be simple to make things better, but chaos theory tells us that changing one thing can have immeasurable consequences… and when you throw in the added difficulties of everything being mediated through George’s unconscious mind, well. Hello havoc. Essentially the narrative consists of George and his quest to be normal, please.

I thought the explorations of George as Mr Average were a really interesting aspect of the novel, because in some ways it seemed to be interrogating the idea of the hero, in life as well as in literature, and also of course pointing out that the idea of ‘average’ is entirely a construction: no one should actually sit completely at the midpoint of any measures. I was absorbed by le Guin’s awfully relentless exploration of dream-logic and what it would do to the world next. But – apparently The Times declared this book should be “read again and again.” I’m not convinced it has that much re-readability, for me.

Spinning a darker stair (review)

Firstly: oh my goodness look how CUTE this is! Seriously, this itty bitty 50-odd page bookling is so cute. Does this count as a chapbook? I don’t know the official definition of chapbook, but part of me thinks this should be one, while part of me thinks no! Chaps won’t read this! This is a ladybook, or a dreamerbook, or something.

Firstly: oh my goodness look how CUTE this is! Seriously, this itty bitty 50-odd page bookling is so cute. Does this count as a chapbook? I don’t know the official definition of chapbook, but part of me thinks this should be one, while part of me thinks no! Chaps won’t read this! This is a ladybook, or a dreamerbook, or something.

Yes, well. Anyway.

This delightful product, whatever it is, comprises two short stories that riff off different fairy tales. Catherynne M Valente’s “A Delicate Architecture” is the first, and I know I read it in Troll’s Eye View but my memory is bad enough that I had forgotten the kinks in the tale. Which was good and bad, since it got to break my heart all over again. This is Valente at her best, spinning an impossible and impossibly beautiful story about a girl and her confectioner father and the dark dark things that can be done in the name of hunger (in all its many variations). This story is complemented by Faith Mudge and “Oracle’s Tower.” While it wasn’t clear to me which fairy tale was being meddled with by Valente until very near the end, it’s clear relatively early on who Mudge is playing with. This does not, of course, prevent the story from working in dark and sometimes sinister ways. This is not a nice story. It is very clever, though, and very nicely told.

Both of the stories are given that extra something by the illustrations of Kathleen Jennings.

The front and back covers are hers, and within there are four more pictures of the women featured in the stories. They’re line sketches (… I am no artist, so forgive me if I get the terminology wrong), and they are delightful and beautiful and add a great deal to the overall feel of the package.

The front and back covers are hers, and within there are four more pictures of the women featured in the stories. They’re line sketches (… I am no artist, so forgive me if I get the terminology wrong), and they are delightful and beautiful and add a great deal to the overall feel of the package.

Also? my copy came wrapped as a present. That definitely adds to its specialness.

Full disclosure: I am friends with Tehani Wessely, owner/editor of Fablecroft (the publishing house responsible for this book).

Galactic Suburbia 57: now with extra Hugo nominations

In which this Hugo nominated podcast is Hugo nominated and discusses the Hugo nominations while being Hugo nominated. Also, the internet is full of things. Some of those things discuss gender, feminism and equality, some have wide ranging implications for the future of SF awards, and some of them are nominated for Hugos. You can download us from iTunes or get us from Galactic Suburbia.

In which this Hugo nominated podcast is Hugo nominated and discusses the Hugo nominations while being Hugo nominated. Also, the internet is full of things. Some of those things discuss gender, feminism and equality, some have wide ranging implications for the future of SF awards, and some of them are nominated for Hugos. You can download us from iTunes or get us from Galactic Suburbia.

Hunger Games: Build up to make a hit

The reviews are in:

Topless Robot

Forbes

Our Alisa

“But in the real world, the character Katniss Everdeen faces an even greater challenge: Proving that pop culture will embrace a heroine capable of holding her own with the big boys. It’s a battle fought on two fronts. First, The Hunger Games must bring in the kind of box office numbers that prove to Hollywood that a film led by a young female heroine who’s not cast as a sex symbol can bring in audiences. And second, for Katniss to truly triumph, she must embody the type of female heroine — smart, tough, compassionate — that has been sorely lacking in the popular culture landscape for so very long.”

The Clarke Award Shortlist:

Christopher Priest’s original post

Cat Valente responds:

“Because let’s be honest, I couldn’t get away with it. If I posted that shit? I’d never hear the end of what a bitch I am”; and further response

Outer Alliance discussion on Gay YA Dystopia & Paolo Bacigalupi

Qld Premier cancels Premiers Literary Award

“Before the election, the LNP pledged to cut government “waste” as part of its efforts to offer cost-of-living relief to Queenslanders.”

Response of Queensland Writers Centre

The Fake Geek Girl at the Mary Sue

Kate Elliott on the portrayal of women in pain & fear

Ashley Judd on the media’s attitude to women and their bodies

Valente on the war against women in the real world

Tehani on Aurealis Awards stats, gender

BSFA stuff – Actual winners

The first post that raised the problems with the ceremony.

A response (there for historical sake, though I think since at least partly recanted)

how the Tweets saw it

Cheryl’s take

**The BSFA issued an apology right about when we were recording**

Jim Hines works through his privileged dumbassery

Kirstyn McDermott works through whether her feminism is good enough

Vote for Sean the Blogonaut for NAFF

What Culture Have we Consumed?

Alex: Monstrous Regiment, Terry Pratchett; Showtime, Narrelle M Harris, Woman on the Edge of Time, Marge Piercy; 2312, Kim Stanley Robinson; The State of the Art, Iain M Banks

Tansy: So Silver Bright, Lisa Mantchev; Kat, Incorrigible, by Stephanie Burgis; Cold Magic, Kate Elliott

Alisa: The Hunger Games (movie and books), The Readers (podcast)

Please send feedback to us at galacticsuburbia@gmail.com, follow us on Twitter at @galacticsuburbs,, check out Galactic Suburbia Podcast on Facebook and don’t forget to leave a review on iTunes if you love us!

2312 promises to be an interesting year

This book just made me happy. Wonderfully, giddily happy. That’s the TL;DR version.

This book just made me happy. Wonderfully, giddily happy. That’s the TL;DR version.

There’s the gender aspects. Robinson goes beyond gender-bending and into gender-thwarting. I first really realised something was going on when a new character was introduced and for the entire interaction, there were no pronouns used. And it’s a gender-neutral name. So… no clue as to whether biologically or otherwise male or female, and it didn’t matter in the slightest; and nor did it matter for the many other characters for whom this was also true. The gender aspect is one where Robinson’s sly use of language and meta-references comes in: there’s a comment somewhere (I wish I had bookmarked it!) where the difficulty in determining sex or gender is remarked on, and the fact that humanity could now be called “ursuline” – because of the notorious difficulty in sexing bears, is the commenter’s note. But I see what you did there, Robinson, and since le Guin is one of my favourite authors, I quite literally laughed and crowed aloud. This society has what ours would regard as the “normal” genders (with “outrageous” (p431) macho and fem behaviours as something of an art form), as well androgyns, wombmen, hermaphrodites, gynandromorphs, eunuchs, and the gender-indeterminate. There are people who have fathered and mothered children at different times, people who never disclose their gender to anyone, and… really the broadest range of sexual and gender identity that I can imagine (actually, broader than I had previously imagined). So, that aspect is a lot of fun – and it’s presented as normal and as a full expression of humanity.

The political aspect comprehensively wooed and won me. It’s common enough – perhaps not so much today, but still sometimes – in science fiction and fantasy to have a monarchy, or an authoritarian regime of some flavour to work within/against, or at any rate a government that can be seen as leaning to the right. And the characters often either agree with it or are actively rebelling against it. Robinson’s solar system is far more complex and interesting. For a start the Earth isn’t given a single governing body; it actually has more countries here, 300 years in the future, than it does today. The other planets and moons often have one controlling authority, but they are disparate in their aims and desires. In fact much of the inner solar system is held together as part of the Mondragon (based on the idea of a Basque town, see here). A non-profit, cooperative-based, economic model aiming at mutual support. Yes please. This is contrasted with Earth, and again I will admit to laughing out loud at this description: “late capitalism writhed in its internal decision concerning whether to destroy Earth’s biosphere or change its rules. Many argued for the destruction of the biosphere, as being the lesser of two evil” (p125). I laughed, and then I wept. Also this: “confining capitalism to the margin was the great Martian achievement, like defeating the mob or any other protection racket” (p127). A system where, overall, I feel encouraged by the politics and economic aims? Not utopian but aiming high and nobly? That makes me pretty happy.

These aspects combined make this an optimistic novel about the future, which also makes me happy. Don’t get me wrong: this isn’t a glorious love-in where nothing bad happens, where there’s sunshine and rainbows and cookies for all. Life on Earth is hard – climate change has had a serous impact, especially if you lived anywhere near the coast (or where the coast used to be…); life on Mercury and the moons involves great difficulties; there is crime and anger and wanton destruction of life. But those things exist today, too. What makes this optimistic is the attitude taken by both Robinson and many of his characters that there is something that even insignificant people can do about it all. Maybe it won’t make a change immediately, and that will be annoying, but long term changes can be worked towards – they’re worth working towards, and enduring the setbacks, because people and institutions can change.

Of course, all of these things are well and good. The story is happy-making too. It’s told largely though the lens of Swan Er Hong, resident of Mercury and restless spirit. Several other characters become important over time, and Robinson cleverly uses chapter titles to indicate which character will dominate (“Swan and Wang” = Swan is most important, Wang will loom large too).

Speaking of chapters, there are sets of Extracts and sets of Lists scattered at different points throughout, too. Extracts are a form of info-dump, with sections of texts literally like they are extracts from news reports, histories, or scientific papers. This is a neat trick and one that felt immersive – because it could easily be Swan or another character skimming books or websites – rather than throwing the reader out by being too info-heavy. And the Lists often feel whimsical, but they certainly add depth; my favourite, in a melancholy way, is a list of words beginning with boredom and escalating to death wish; it captures quite nicely the sentiments of at least one character at the time. (There’s also a wonderful list of women honoured by having a crater named after them, from Annie Oakley to Emily Dickinson by way of Sappho and Xantippe.)

But back to the story: it’s a curious one really. For much of the novel, it feels like the story is happening around the characters, but they’re not often directly involved – at least, not in the big events: destruction of a city? Not there at the time. These big things have a big impact on our protagonists, but – much like we normal mortals experience events – those events act on them, rather than (mostly) being caused by them. For this reason Swan, for all she has important connections and is moderately famous, feels remarkably like a normal person. The narrative itself is basically a whodunit that gets bigger than expected: Swan’s grandparent has died and left a somewhat unexpected inheritance, and then soon after her home, the city of Terminator on Mercury, is destroyed, leaving Swan determined to help find the culprit. This leads her all over the solar system (up to and including the moons of Saturn have been comprehensively colonised), interacting with people of all shapes and sizes (literally; being a tall or a small is more of a division in this society than gender). There’s intrigue, and dismay, and maybe-love, and some wild ideas for how people in three centuries might get their kicks, from tampering with one’s physiology to some rather extreme sports. Swan and friends do end up having an influence on events, but the manner and the outcome are far from predictable.

Swan herself, as I said, is a fairly normal-seeming person. She gets cranky and has wild ideas and is frequently hard to please; she is contrary and independent and determined and wants the best for the universe (mostly), so who can’t people just agree with her when she’s clearly right, dammit? The supporting cast – Wahrum and Wang and Genette and others – are varied, from police to scientists to politicians, with a variety of sexual orientations (when it’s even specified), and a plethora of priorities and ambitions of their own. The society as a whole is gloriously well realised and complex, but familiar as human nonetheless.

In sum, then, this is a realistic (non-utopian), largely optimistic, enthusiastic look 300 years into the future, with complex and occasionally frustrating characters who may well remind you of people you know. This is what I would like science fiction to be like a lot more frequently.

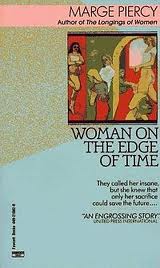

Woman on the Edge of Time

This book… blew my mind. It’s angry, and demanding, and confronting, and seriously amazing. It’s also not at all what I was expecting, but that’s quite ok.

This book… blew my mind. It’s angry, and demanding, and confronting, and seriously amazing. It’s also not at all what I was expecting, but that’s quite ok.

Connie Ramos has been committed to a mental institution (again) in the mid-1970s. Perhaps the first time she ought to have been there (although maybe not…), but this time she doesn’t. Which doesn’t make any difference to the authorities, who view her – as a woman, a previously incarcerated person, as a Chicana, and with powerful male figures banded against her – as unreliable and someone To Be Dealt With. Her experiences within the institution are demeaning and seem aimed at dehumanising her and her experiences. What makes this even more unbearable is the thanks Piercy gives at the start, “to people I cannot thank by name, who risked their jobs to sneak me into places I wanted to enter… the past and present inmates of mental institutions who shared their experiences with me” – her fiction is, then, not fiction at all, but a reflection on reality. And that is heartbreaking, if (tragically) also not surprising. Her experiences within the institution – begging for treatment for injuries, the cold carelessness of the staff – are heightened when a doctor chooses her to be part of an experiment in ‘curing’ certain mental ‘problems’ (like aggression – particularly in women – and being gay). This is not an easy read. It is a sobering and worthy one, though.

… but hang on. This doesn’t sound like the sort of thing she usually reads! Oh yes. Connie is also in contact with someone from the future (150 years ahead, or so). Luciente first speaks to her and appears in Connie’s time, but they then discover that Connie can go through to Luciente’s time, and experience what life is like then. Piercy does a wonderful thing with this future society in not making it utopian, tempting though I’m sure that would have been. It is certainly better than the America of Connie’s experience – enough food for everyone, a broader understanding and expectation of family and care, no capitalism – but there are problems, such as jealousy and anger, still. And indeed there are aspects which Connie finds quite unacceptable, especially in their broadening of the maternal role, which she sees as women having given up their only claim to power. Here, the idea of family is a negotiated one, and multiple partners take on the role of breastfeeding; someone who is tied too closely to another (as we would expect from life partners) is deemed to have overstepped society’s boundaries. Of course, the contrast between Luciente’s experiences and Connie’s makes Connie’s all the harder to read.

Connie is not the easiest character to read. There are times when she was frustrating precisely because she fits so much into the mould that society wants her to fill – I can’t fault her for that, but I wasn’t even born during the times she is experiencing, so there was of course a part of me that just cried out for her to rebel, please! For your own sake! – which I understand is totally unfair, but nonetheless it was there. Luciente is a slightly easier character to read, even though it’s through the lens of Connie and her experiences; she’s far closer to what I am used to reading about. This disjunction between the characters, and my reactions to them, was a really interesting aspect – and, I admit, added to the discomfort of reading, which led to its own interrogation.

This is a book which interrogates power on the basis of gender, education, race, and perceived place in society. It shows power as constructed, it shows power to be dangerous, and it shows that power shared is more useful power. It doesn’t claim to have all the answers, but it certainly suggests that things could be substantially better. And that today’s world has the power to bring about change… or not.

Just read it.

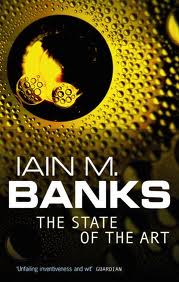

The State of the Art: verdict = poor

I was quite disappointed by this collection, unfortunately. It lacked any… panache.

I was quite disappointed by this collection, unfortunately. It lacked any… panache.

“Road of Skulls” is hardly a story, barely a vignette – seems like a riff on Waiting for Godot without the existential angst. The last couple of paragraphs are clever, bit they made it feel more like a prologue to a novel than a standalone story.

“A Gift from the Culture” is about someone having left the Culture to live on a normal planet, and then getting blackmailed to do something only a Culture person could do. It had a lot of potential – how a relationship might work with such a disparity of backgrounds, how someone from the Culture might respond to being blackmailed… but in the end it did not live up to any expectations.

There’s another vignette in “Odd Attachment,” where a first contact scenario is played out from the point of view of the vegetative alien, who would rather being thinking about his lady love, actually. Amusing enough, but not exactly mind-blowing.

The story that had the most impact on me was probably “Descendant,” entirely focussed on one man, his thoughts and his interactions with his spacesuit as he trudges around a barren little world trying to find the one settlement on it, after being blown out of the sky. Melancholy in a readable way.

I found “Cleaning Up” a bit frustrating, because while it had a fun premise – alien gifts start appearing on the earth, how does the West deal with it when the Soviet is still a threat, etc – the characters were so unpleasant as to be almost unreadable.

The absolute lowlight for me was “Piece.” Less a story and more an anti-religion diatribe. The author is recounting two experiences of having been the oh-so-intelligent and smug atheist intellectual confronted by two religious nuts, over the span of 15 years; one an old man, a Christian who dislikes science, the second an otherwise intelligent Muslim man (this is the perspective the reader is presented with) who objects to The Satanic Verses. The conclusion may be trying to suggest that it’s not quite as obvious as the protagonist is suggesting, but it does nothing to redeem the story.

The second last story is the novella “The State of the Art,” another piece about the Culture. Here, the Culture comes into contact with – wait for it – Earth, in 1977. The focus of the story is on Sma and her experience of Earth, as well as her interactions with some of her fellow Contact personnel and the ship Arbitary. While it was interesting enough to consider how the Culture might view Earth, especially perhaps at that time – Apartheid going strong, genocide in Cambodia, war in Ethiopia, etc – in the end it once again felt more like an excise for a rant about everything that is wrong with the world, wrapped up in a story that only just better than average. If I sound bitter, it’s because I am – I expected way more from Banks. Maybe I was setting the bar too high; maybe the short form just doesn’t work for him.

The last story is “Scratch,” and I didn’t really read it for the same reason that I haven’t read the last twenty or so pages of Joyce’s Ulysses (well, also I just didn’t get up to it): stream of consciousness does absolutely nothing for me, and when it’s several people’s worth of consciousness, even less.

So there you go. Disappointed.

Blue Remembered Earth: a belated mini review

So… I read this ages ago, and while I talked about it on Galactic Suburbia (well, rambled incoherently, probably) I just haven’t got around to writing about it properly. The longer I left it, the harder it was to come to it. Until we get to now, when my pile of books that I want to review is growing rapidly, so obviously the thing to do is to go back to the beginning and get this one done.

So… I read this ages ago, and while I talked about it on Galactic Suburbia (well, rambled incoherently, probably) I just haven’t got around to writing about it properly. The longer I left it, the harder it was to come to it. Until we get to now, when my pile of books that I want to review is growing rapidly, so obviously the thing to do is to go back to the beginning and get this one done.

Natch.

I’m sure I had lots of interesting things to say, but I have of course forgotten many of them in the intervening months (it was November that I read it). What I haven’t forgotten is how much I liked it – and before Sean or someone teases me about being Reynolds-obsessed, I wasn’t a huge fan of his last novel, Terminal World, so let’s just accept that I can indeed be objective and move on.

The novel opens with the death of a family matriarch, an event which spins all sorts of interesting consequences especially for one grandson, Geoffrey, and for his sister Sunday as well. They are led by various cryptic clues to caches hidden by their grandmother over an extended period of time – which eventually lead them to discover a secret which will change their family, their family’s business, and the way humanity views its future.

Geoffrey is an intriguing protagonist. He is the black sheep of the family, evincing little interest in the family business – essentially freighting stuff around the solar system – and generally annoying his more committed cousins. His interests instead lie with elephants, conserving them and getting to understand them better. This is such an off-beat love for a science fiction novel that I was immediately delighted, I have to say. His elephantine interests do end up having some bearing on the plot, but not as much as I might have expected; it’s mostly just what he’s into. I also really liked that the family is African; Tanzanian, to be precise. This is just something that is – Africa as a whole has come through into the 22nd century doing fairly well, and taken its place as a developed continent, leading the way in some areas.

This is near-future Earth (by Reynolds standards) – the 22nd century. It’s post-global climate crisis, which wasn’t quite as bad as it might have been but still quite traumatic thankyouverymuch, and there are some moves underway to improve the ecosystem. Much of the solar system is inhabited, to one degree or another – Mars and the Moon quite substantially, understandably thinning out as you move away from the Sun. The economy is going fairly well in most places; politics doesn’t get a huge amount of pagespace. There is new and interesting technology in terms of communication, and transport, and living underwater. This all sounds fairly familiar – either from our world or from standard science fiction – and a nice enough place to live, and it is… until you start realising how insidious the Mechanism is. The Mechanism would have Orwell spinning in his grave. It knows where you are and everyone else is at any given time, it knows what you are feeling, and if you are feeling aggressive it is able to stop you before you act on that aggression. It is CCTV and Google knowing your search history and ID cards taken to a scary degree. And what is perhaps most scary is that Reynolds does not give it a central place in his narrative. It is simply there. It’s accepted as a part of society by most of humanity – not a good part or a bad part, usually, but a necessary part, an obvious part. And if you buck against it – well, you’re a problem.

Overall… interesting, well-rounded characters; well-paced action; nicely developed society with pleasing as well as ominous aspects; and it’s the first in a trilogy. I am really looking forward to the next two.

Rocannon’s World

I believe this was le Guin’s first published novel, and I think it shows – it shares some themes with later novels, but the action is a bit jerky and occasionally confusing. (Also, the front cover makes it look a little bit too Masters of the Universe.) Nonetheless, it’s the first of the Hainish cycle which I generally adore, and I did enjoy it.

I believe this was le Guin’s first published novel, and I think it shows – it shares some themes with later novels, but the action is a bit jerky and occasionally confusing. (Also, the front cover makes it look a little bit too Masters of the Universe.) Nonetheless, it’s the first of the Hainish cycle which I generally adore, and I did enjoy it.

The book opens with the tale of Semley, who marries away from her family and comforts into an ancient but impoverished noble family. She determines to find an ancient necklace of the family, to restore some honour to them, and in doing so must have dealings with another, humanoid, race on her planet. To find the necklace they take her on a great adventure – to another world, although she doesn’t realise it – but her return is met with grief.

All of this is a prologue, and could easily pass as a short story in itself. Semley reminded me somewhat of Arwen, from LOTR, of what a continuation of Arwen’s story could have been. There’s certainly a LOTR/Celtic mythology feel to the different humanoid races on this world, and some of their interactions.

The rest of the story is about Rocannon, one of the people Semley met on her journey, and who is now directing an Ethnographic Survey on her home planet, many years later. Things go badly however when his ship is destroyed by unknown assailants, and all of a sudden he’s stuck on (to him) an exceedingly backward planet that might just have become the front line in a war the League has been anticipating for some time. He therefore has to deal with potential baddies being on this world as well as being cut off from all contact with his own people. This is, naturally, a difficult position to be in.

There’s action, there’s angst, there’s discoveries about some of the truths about the different humanoid races on the planet. Rocannon learns much about himself, as a leader and as a stranger and, most humbly, as a frail human who can actually learn things from seemingly backwards people.

It’s not as disturbing and earth-shattering as something like The Word for World is Forest, and I can imagine that an older le Guin might have added some more meaty stuff about gender or colonisation into the mix, which are just barely hinted at here. Still, like I said it’s an enjoyable enough story, and it’s largely very well written – there’s some beautiful prose. Interestingly this is one of the differences I noticed; this novel feels a bit more… poetic, perhaps, than many of her later novels, which while beautiful tend (to my mind) a bit more towards the sparse.

Galactic Suburbia: best of

Galactic Suburbia – quick picks from the best of 2011

If you’re just joining us, and want to try out Galactic Suburbia for the first time, here are the top episodes that we think represent the best of 2011.

If you’re just joining us, and want to try out Galactic Suburbia for the first time, here are the top episodes that we think represent the best of 2011.

Episode 36: Spoilerific Book Club: Joanna Russ Featuring: “How To Suppress Women’s Writing,” by Joanna Russ; “The Female Man,” by Joanna Russ and “When it Changed,” by Joanna Russ

Episode 47: 24 November 2011 In which we bid farewell to the queen of dragons, squee about 48 years of Doctor Who, dissect the negative associations with “girly” fandoms such as Twilight, and find some new favourites in our reading pile.

Or if you’re feeling adventurous, you can check out our entire 2011 catalogue of episodes! Thanks to our silent producer for gathering those links.

The Selected Works of TS Spivet

I came to this book really expecting it to be speculative fiction. I don’t know why; I’ve been meaning to read it for years and all that time, I was quite convinced that it had a fantasy element to it. And I guess it sort of does, in that it’s an entirely unlikely story, but it’s not the out-and-out fantasy, or even the Charles de Lint-ish fantasy, that I was expecting. I really liked it though, and I thoroughly enjoyed the marginalia – in fact it’s this element that really makes it stand out.

I came to this book really expecting it to be speculative fiction. I don’t know why; I’ve been meaning to read it for years and all that time, I was quite convinced that it had a fantasy element to it. And I guess it sort of does, in that it’s an entirely unlikely story, but it’s not the out-and-out fantasy, or even the Charles de Lint-ish fantasy, that I was expecting. I really liked it though, and I thoroughly enjoyed the marginalia – in fact it’s this element that really makes it stand out.

TS Spivet is twelve years old. He’s also a cartographic genius, and obsessor. He maps everything: from the way the water moves across his parents’ property, to the motion vectors of a man on a bucking bronco. His artistic skill extends to drawing insects and animals and probably anything else that captures his interest. But it’s maps he loves the most.

Life is already difficult for TS as the story opens. His parents are being difficult, which is nothing unusual really; his father appears disappointed in him for not being more like his outdoors-y brother, his mother is obsessed with insects, and… well, that would be a spoiler. It’s just not all sunshine and joy. And then the Smithsonian calls, asking him to come and visit them because of his amazing drawings that have made their way to that hallowed institution. So TS takes off, across the entire US, to get to the Smithsonian where he feels he might be appreciated and where he can do some good.

(This is where I was expecting some fantastic element. I think I was hoping for something like in Libba Bray’s Going Bovine. It didn’t happen. It’s still a good story though.)

TS is an… interesting… character. I hadn’t expected to be quite so enthralled by a twelve year old character, and the reality is that he doesn’t act like one. He’s an innocent, in his expectations of people and his trusting nature, which is occasionally abused by adults who are just trying to get their own way. But at the same time he has, and develops, a canny sense of the world.

I enjoyed the story as a whole, of TS’ journey – and I have no idea about the places in America he travels through, but I hope Larsen has captured something of their true spirit, because it certainly feels that way. However, probably my absolute favourite part was reading about TS reading his mother’s journal about one of her husband’s ancestors, Emma Osterville. A woman like TS in many ways, precocious and fascinated by the natural world, who becomes a geologist. In fact I was so taken in by this story, and it had just enough plausible elements, that I did indeed google her… only to discover that she is as much Larsen’s creation as TS. Oh, so sad.

Aside from the somewhat-fey TS, the element that really sets this book apart is its physical nature. Many of the pages look like this, with marginalia and arrows added in – usually just on the sides but sometimes top and bottom too. They elaborate on various points of TS’ life and family; they include a number of his maps and other drawings; and generally provide a commentary that would otherwise be difficult to include but without which this would not be nearly so rich. Think Terry Pratchett’s footnotes, but more visual.

Aside from the somewhat-fey TS, the element that really sets this book apart is its physical nature. Many of the pages look like this, with marginalia and arrows added in – usually just on the sides but sometimes top and bottom too. They elaborate on various points of TS’ life and family; they include a number of his maps and other drawings; and generally provide a commentary that would otherwise be difficult to include but without which this would not be nearly so rich. Think Terry Pratchett’s footnotes, but more visual.

I can definitely recommend this to readers of young-adult fiction. While it isn’t fantasy, it does have that vibe about it; it will also appeal to those who dislike fantasy, and want more ‘mainstream’ literature. The prose is easy to read, elegant, and occasionally poetic; the illustrations add a great depth and joy.