Women’s History Month series

Links to interviews (and transcripts) with Melbourne women who protested against the Vietnam War and the National Service Act.

(list continues below)

Continue reading →Object Lessons: Lipstick

I read this courtesy of NetGalley and the publisher, Bloomsbury. It’s out on Feb 19.

I have a fraught relationship with the idea of femininity. I obstinately rebelled against participating in most forms for a long time, for complex reasons that mostly had to do with what I thought was important about my identity. Eventually, I realised I was being stupid, and that things I enjoyed were not things that got in the way of who I was. I was 35 when I decided actually, I do like lipstick, and started regularly wearing it to work, and when I went out.

So this new Object Lessons, about lipstick, and in particular about how it is viewed, used, stigmatised, discussed, and historicised? This book was written for me.

And it is very well written. As with all of this series, the book is intensely personal as well as being well researched and reported. Given the way lipstick is viewed by different groups and individuals I particularly liked the way G’Sell incorporated the views of other people – those who love wearing it, and those who hate it, all for valid and important reasons. There aren’t all that many apparently innocuous objects that can get such intense, contradictory, and equally important reactions (although the bra does spring to mind, as it were).

As always, we get some history – folks of all genders wearing makeup in ancient Greece, 1930s film femme fatales, etc – as well as some anthropology (Iranian women wearing lipstick, examining the perennial comment about sales of lipstick going up in times of economic hardship), along with the intensely personal reflections.

The list of chapter titles will give a sense of what the book encompasses:

- Painted Ladies and Tainted Men

- Painted Ladies and Painted Men

- Lipstick Feminism and Sticky Pleasures

- Whitewashed Beauty, Appropriation, and Lipstick Legacies

- A Femme-Friendlier Future?

I loved it. This is a book for anyone who has thought about what it means to wear lipstick. or makeup more generally.

Object Lessons: Ballot

You can take compulsory voting from my cold dead hands.

I read this book c/ NetGalley and the publisher, Bloomsbury. It’s out now.

I love every Object Lessons book. In some ways, this one is like the rest – part history, part social commentary (almost anthropology), part personal experience. However, it’s a much more immediately relevant topic than, say Skateboarding or Perfume. As well, all of those have been partisan – they’re written by people who like skateboarding and perfume – but it’s much more obvious in this one: the author is outspokenly progressive – votes Democrat, because America, although – happily – she is also very clear on the failures of various Democratic leaders.

Compulsory voting forever.

One important thing to note here is just how American this book is – more noticeably than many of the others I’ve read. The author is American, and it’s one of the most personal Object Lesson I’ve read, so the narrow focus flows from that. Which is not inherently a problem – American voting is a fascinating / appalling thing to view from afar. What is… let’s say disconcerting is the way the book is written without acknowledging that it is, functionally, entirely aimed at an American audience. Does anywhere else vote on its judges? The local equivalent of district attorneys or sheriffs? Maybe they do, but nonetheless – that shit’s wild. Plus all the state vs federal laws, not to mention the college system OMG. Thus much of what the author says is not automatically applicable to my experience, and I would guess not to the experience of many other people around the world. (This comment also reflects that I had not carefully read the blurb, so partly this is on me.)

I will fight for compulsory voting.

(Note: it’s actually not compulsory to vote. It’s compulsory to get enrolled; then it’s compulsory to choose between a fine ($100) or rocking up at the election and having your name marked off. No one compels you to mark a ballot and put it in the box.)

I knew some bits and pieces examined here. The whole voter ID thing, and how it’s manipulated – wild. (Doesn’t happen in Australia.) “Use it or lose it”?? See note re: compulsory voting. The ways in which prison populations – mostly filled with people who can’t vote – are still counted as population for purposes of figuring out county borders etc?? Everything about this system makes me, an Australian with a clearly perfect and incorruptible election system,* laugh at the idea of America as a wonderful democracy.

Another thing to note is that this is not a history of the physical ballot process, which I initially assumed it would be. The process (as it happens/ed in the USA) is covered super briefly. Instead, this is essentially an overview of voting practices in the very recent US past. Which is certainly interesting, if not what I thought I was getting (see previous comment about not having read the blurb, and that’s on me.)

It’s very well written, and completely depressing.

* This is a joke.

The Man Who Stopped the Sultan

Read courtesy of the publisher and NetGalley. It’s out at the end of January, 2026.

This book is pretty great. For a reader even vaguely interested in the Europe and Ottoman Empires of the 1400 and 1500s, it provides a brilliant perspective that is often missing from other, entirely Euro-centric accounts I’ve read.

Did I know Henry VIII, Frances I. Suleiman, and Charles V were all around the same age?? No I did not. Doesn’t that give the 1500s a slightly different complexion. (Also I love the dismissal of Henry VIII and England as not particularly relevant to the happenings on the Continent at this point….)

This is larger than JUST a biography of Gabriele Tadino, although it is also that. Tadino is himself a fascinating figure – an engineer when military engineering is completely changing in reaction to technology, basically in the centre of things because of birth (living near Venice when shit is getting real, thanks very much not-so-Holy, definitely-not-Roman Emperor) and then being persuaded to join in with the Knights of St John over on Rhodes when Suleiman and his crew are laying siege. Tadino is not perfect, and there’s also bits of his life where the records completely dry up – but Albert has done a convincing job of recreating a lot of his experiences, and suggesting the whys and wherefores around them.

Alongside the Tadino exploits, though, this is also a magnificent examination of European and Ottoman relations in this key period. I don’t know all that much about Suleiman, nor the Ottomans at this time more broadly – but I know more now, and my disgruntlement at writing European history of the 16th century without reference to what was going on over East, and indeed well into central Europe, is Large.

Well written and accessible for the generally historically intelligent reader – no need to have very specific knowledge of people or places – this is a really great book.

The Everlasting, by Alix E. Harrow

I keep not reading books by Alix E. Harrow as soon as I should, but at least this time I didn’t leave it a couple of years. Which means really I’m fairly up to date, right?

TL;DR this book is simply superb and if you have any interest in knights and adventure and time travel and stories that do very clever things with stories, this needs to be at the top of your To Be Read pile.

My thoughts on this magnificent novel are split into two bits: thoughts for readers with extensive (some might say tragic) Arthuriana knowledge, and thoughts for everyone else.

For everyone else: truly this is a beautiful novel of love and determination and the power of story. It can and should be read as a romping adventure story across time, with its share of heartbreak and despair but also a great deal of hope and bloody-minded teeth-gritting stubbornness. It can and should also be read as a dissection of the uses to which Story and History can be put, at a personal and a national level, which has a significant element of caution as well as its own element of hope. This is also a novel with fantastically well-developed characters: Sir Una, the knight whose image is used Kitchener-ly for Dominion wars (and I was also put in mind of Emily Blunt’s character in Edge of Tomorrow), whose devotion to her queen a thousand years ago is literally the stuff of legends. Owen Mallory, a nearly-failed historian with an alcoholic deserter father, struggling with his own demons, unexpectedly flung into Una’s story. The queen herself, Owen’s academic supervisor, the murderous horse – there’s not a misstep throughout.

… for the Arthuriana tragic, there’s even more going on here. The historian is Owen Mallory. Dominion is playing on the idea of England; the Arthur story is (or perhaps was) after all England’s national myth, in many ways, as Una’s is. There’s a wonderful interplay between Owen and his academic mentor about the Everlasting stories as a palimpsest, and stories being changed to fit a national moment, and irritation at audiences who think the later stories are the authentic ones – all of which applies to Arthuriana, in amusing and sometimes heated ways. There’s the idea of a knight being undying, the reference to a grail, most of the other knights’ names are plays on names from the various cycles – there are so many moments at which I just flailed at Harrow’s cleverness.

I adored this novel. And I read it just a few weeks after reading Tasha Suri’s The Isle in the Silver Sea; these ideas about stories and nations, their use and abuse, are clearly floating around in the zeitgeist. But I hasted to add that having read one does not detract from reading the other – the opposite is true: reading both (maybe not one after the other) is more like… some clever analogy with structures supporting one another. I’m sure you get the idea.

Die Hard, by Jon Lewis

I received this c/ the publisher, Bloomsbury.

Yes, this is a book. No, it’s not the book that Die Hard the movie is based on. (Yes, at least to some degree the movie is kinda based on a book. Ish.) Yes, this is an academic-ish take on the movie. Yes, I received this just in time for Christmas, and yes I am Gen X enough that this fact made me giggle-snort.

In under 100 pages, Jon Lewis situates the movie Die Hard within Reagan-era politics and economics. The way it sits within an America still coming to grips with its loss in Vietnam and the events of the American embassy in Tehran, among other things. And the way Americans view terrorism and terrorists, too, and how that connects to Hans and his crew – these things may not have been directly in McTiernan’s mind, but the zeitgeist is real.

The book also situates the film within the larger action movie oeuvre, and situates John Maclaine alongside and against other action-movie heroes. I did not know that the director also did Predator (and The Hunt for the Red October)! I had no idea that the white ribbed singlet – the wife-beater – so iconically (for me) worn by Maclaine was first made iconic by Brando in A Streetcar named Desire. But I can absolutely see how the libertarian hero – often but not always affected by experiences in Vietnam – were a significant feature of this moment in American cinema. The “hard-body” heroes of Stallone and Schwarzenegger are different from the slighter Willis – what that means for relatability is interesting – and I had no idea that Maclaine’s pithy quips almost certainly derive at least in part from Willis’ TV detective.

Lewis spends a surprising amount of time recounting the beats of the film – surprising because I assume no one is picking this book up who hasn’t already watched the film (possibly several times, maybe not necessarily at Christmas) – but does usually tie this narrative recounting in to his theorising. My one significant gripe is that in listing the “whammies” – the moments of violence that punctuate the story – Holly’s punching of the reporter isn’t mentioned. It’s not as excessively violent as other moments, and it doesn’t kill anyone, but it’s definitely a shock. And one of the threads that Lewis follows throughout is the question about whether Maclaine is a decent husband (no), and – I think by extension – a decent father. This moment shows Holly getting to defend the kids, rather than Maclaine.

Anyway: if you or someone you know has a habit of watching Die Hard for Christmas, or quoting any of the eminently quotable one-liners at dubiously appropriate moments, and they don’t mind a bit of broader cultural discussion this is likely to be a good book for them.

Artifact Space, Miles Cameron

I received this to review courtesy of the publisher and NetGalley.

Is Marca Nbaro really just too good, too fast? Yes.

Is some of the ‘science’ highly dubious, and does much of the technology require quite a lot of hand-waving? Also yes.

Did I absolutely devour this book and am I eyeing off the sequels? Also yes.

Nbaro grew up in an orphanage, which was hell, and now she’s shipping out on one of the nine greatships of human space, the Athens. It’s all she’s ever wanted to do and be. Of course, getting there wasn’t at all straightforward, and the first few weeks aren’t straightforward either. And then when things settle down for her personally, things go very sideways for the ship.

One thing I appreciated, in my current need for not-too-confronting fiction, is that we don’t start off in the Orphanage. There’s enough to understand just how dreadful Nbaro’s life was there, but there’s no dwelling on the horror. Instead, this is a very smartly paced story: it’s basically the written version of an action movie, and it’s good at it.

I can’t quite figure out the politics behind the human world here: Nbaro hasn’t exactly joined the military – they’re a merchant service more than a military – but there are nonetheless marines, and the ship has weapons… everyone is encouraged to be involved in trade while they’re serving… it’s a weird mix of capitalism and socialism. Doesn’t really bare close examination, but at least it’s slightly different from unrestrained capitalism. Mostly.

Look, overall, this is a swash-buckling action novel with an outrageously clever and capable lead character who is nonetheless very appealing, and I enjoyed it a lot.

Taco, by Ignacio M. Sanchez Prado

I received a copy of this from the publisher, Bloomsbury, at no cost. It’s out now.

I love everything about the Object Lessons series. Basically I’ll read every single book, no matter the subject matter. In this case, the subject matter is a bonus: I am a massive fan of food history, and food as social commentary. The taco works beautifully for that.

I am Australian, which means I have little knowledge of “the taco” as cultural object. My first experience was your classic Old El Paso hard shell, and I was well an adult before I discovered that this was not the “authentic” way to eat them – and having said that, Sanchez Prado’s discussion about the question of authenticity is a thing of absolute beauty. I knew that there was controversy within the US about Mexican food, because racism; I knew that “Mexican food” is a multifaceted thing. Sanchez Prado brings all of this to light in a rigorous and readable way – within the under-150-pages context of an Object Lessons book. He provides an extensive reading list, too, for those who want to go further.

This is a fabulous celebration of what was once street food, poor food, and has now suffered “elevation” and popularisation and has become symbolic of much, much more than some food wrapped in some other food. It’s a great introduction to a lot of issues. Definitely one for the food nerd in your life.

Fearless Beatrice Faust

I very rarely read biographies of modern people. Faust only died in 2019, so that’s VERY modern by my standards. But I’ve been interested in how people approach modern biographies, for a project, and so this one was recommended. Having enjoyed Brett’s “From Compulsory Voting to Democracy Sausage,” I was fairly sure I’d enjoy her style, so this seemed like a good option.

Turns out, Faust was an amazing woman. Would I always have agreed with her? Oh no. Would I probably have found her abrasive to work with on a committee? Oh yes. Would I nonetheless have loved to be a neighbour, occasionally going over for coffee and hanging out? For sure.

Faust had a difficult upbringing: her mother dies from childbirth complications, her father is distant, her eventual stepmother unpleasant, and Faust herself is a sickly child (and continues to have multiple chronic conditions for most of her life, which are an enormously complicating factor for her). Yet she is clearly highly intelligent; she gets into Mac.Rob, the select-entry Melbourne girls’ school, and then Melbourne University to do an honours degree in Arts, and eventually an MA. Over her lifetime she writes many tens of thousands of words, and basically becomes a public intellectual – but not an academic, mostly because of misogyny.

Faust was extremely open about her life: her sexuality and sexual experiences, her abortions, her accidental addiction to benzos – all were fuel for public talks, articles, government submissions, and the many letters she wrote to friends.

She was also the founder of the Women’s Electoral Lobby, a key member of the Abortion Law Reform League, and various other women-focused campaigns. Her relationship with “women’s lib” and some aspects of feminism were fraught – she’s just that bit older than many of the agitators of the early 70s – and she definitely had some views that 1970s feminists had a problem with. In particular, some of the ways she talked about pronography, and – even more problematically – her apparent defence of some paedophiles were very troubling. Brett goes into these topics in great depth, sympathetic to Faust in that she tries to understand her views as well as possible, and present them fairly, but not so sympathetic that Faust gets a pass when she is saying unwholesome things.

Brett’s overall style is intriguing. She was approached by Faust’s friends, after she died, saying that she would be a good subject – and Brett said yes for many reasons, including the personal connection (living in Melbourne, some of the same haunts). Brett is not absent from the text, and I appreciated this aspect a lot. That’s not to say that Brett makes it all about her. I mean that Brett will mention when Faust’s reasoning is ambiguous, or when she got something wrong; and in dealing with some really hard topics – like her views on paedophilia – Brett wrestles with why Faust may have thought the way she did, and also calls her out for views that are pretty clearly inappropriate by today’s standards. Brett insightfully considers the question of whether Faust would be considered a TERF today, because she believed that biology was a significant part of a person’s identity; she concludes that it would be easy to say yes, but that Faust’s view is more nuanced than many TERFs, so perhaps not (Faust also didn’t seem to have a problem with a trans woman she spent some time with).

Beatrice Faust absolutely deserved to have a biography written about her. I’m glad Judith Brett was able to do so.

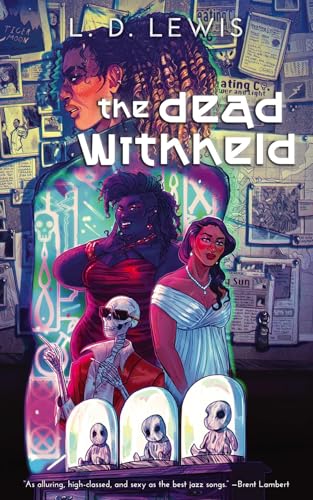

The Dead Withheld

Oh look, another Neon Hemlock. Am I finally catching up on all of the novellas that have been piling up in my electronic TBR? Yes I am!

I love it when folks play with the hardboiled detective story, and make it way more interesting than ‘morose middle aged white man who drinks too much and investigates sad crimes.’ In this case, we have ‘morose unclear-aged woman who drinks too much and investigates sad crimes’ – who can also see ghosts (not entirely unusual in her town) and summon them, occasionally has to deal with demons, is in a friends-with-benefits relationship with Carmen, a demon running a bordello… and got into the PI business in an attempt to find the killer of her lover, now dead several years.

Dizzy is a wonderful character. Once a musician, she’s given that up to be a PI, and she is currently fairly messed up by the unanswered questions in her life; and she has done some questionable things in trying to resolve them – violence, and holding souls captive, to name just two. She’s also a devoted and fierce friend, honest about her failings, and has the sort of drive to get answers that can make or destroy a person.

Exactly when and where the story is set is opaque – there’s mention of “the Former United States”, but if there are clues about exactly where this is set, this Australian could not find them. But that’s irrelevant to the story, because it’s not about technology it’s about magic. The story also doesn’t care about politics; it cares about love, and revenge, and finding your way after you’ve been lost for a long time.

Again: it’s Neon Hemlock. High quality.

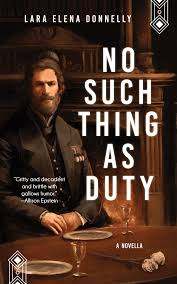

No Such Thing As Duty

Do I know anything at all about W. Somerset Maugham? I do not! Have I ever read anything he wrote? I have not! Did I still enjoy this fantastical take on a period in his life? Certainly did!

William is in Romania. He is dying of TB, and he has left his unhappy marriage – but also his daughter – in England. His lover Gerald is somewhere on the western front, current fate unknown. On paper he is working for a newspaper; in reality he is… sort of a spy. Ish. It’s World War 1, but you’d be forgiven for not realising that – there’s only one mention of the Kaiser, and no other leaders. In fact initially I thought it was WW2 from some other hints, but that mention of the Kaiser seals it.

An assignment comes to William: contact a man who can apparently get one of their agents out of Bucharest, which an Englishman would be unable to do. And so he contacts Walter, and they start getting to know each other, and things happen, and Walter is a surprise.

It’s a Neon Hemlock, so you know you’re going to get a) quality and b) queer content. This novella does not disappoint; it’s well written, well paced, and made me go look up Maugham’s life to see where Donnelly had shoehorned this story in.