Troll: A Love Story

On the one hand, this is a beautifully written story that deals with some fascinating issues. And trolls are real.

On the other hand, I was uncomfortable with the implications of some of the relationships.

So, the first hand: it is lovely, and made all the more impressive by the fact that it’s translated – that can never be an easy task. I love the fact that it alternates story with ‘non-fiction’ grabs from pseudo-websites, dusty old tomes, poems and mythology – some of those are real, I’m pretty sure – and newspaper reports. I know that some people find this annoying; don’t read the book if that’s you. And I know that sometimes it really doesn’t work. But here I lay claim that it adds wonderfully to the depth surrounding the central idea of trolls being a real animal, known to science for the last century or so, and that this story is seeking to add to what humanity knows about Felipithecus trollius. Additionally, although there is a central narrator – Angel – as the story proceeds more of the incidental characters get to add their own perspectives, also in the first person. I know some people have found this changing around to be irritating or confusing, but at least in my edition each chapter clearly labels who is speaking, so rather than confusing I found that it added to the richness of the novel.

Sinisalo raises a diverse range of issues in her story, some more central than others. Trust and love and manipulation; ethics in art and journalism and business; the relationship between humanity and the natural world; mail-order brides, sex as power, desire as all-consuming. Angel, the central narrator, finds a wounded young troll and decides to care for it… which leads to encounters with a neighbour, an ex-lover, a would-be lover, and an object of his affection. Plus a business opportunity.

Which leads me to the other hand. And from this point on, SPOILERS.

Firstly, I know Angel ended up feeling ashamed of taking advantage of the troll, but it was still an unpleasant thing to do – taking advantage of Pessi’s trust in him for entirely mercantile purposes. Given how much Sinisalo works to make Pessi seem if not human then certainly above the animal, I really didn’t like it. Again, I’m sure that was the point, but it doesn’t matter; I still read it, and felt uncomfortable.

And then there’s the implications of the relationship between Pessi and Angel. Perhaps it’s prudish but I was very uncomfortable by Angel’s sexual reaction to Pessi. This is partly because Pessi is coded as being quite young, so the power differential of age exists; partly that Pessi is clearly in a submissive position with regard to Angel in tribal terms, so again the power differential; partly, hello different species – where Pessi is <i>not</i>, especially at first, coded as being as capable/sentient as a human. I know that Sinisalo is trying to problematise issues of desire and sexuality – Palomita’s experience as a mail-order bride is certainly not meant to be endorsed but is still far more socially acceptable – but… it was a problem for me.

Lastly, the ending. I knew it was coming – that Sinisalo was working up to the idea that trolls were either evolving, and catching up with humanity, or that they had always been that clever and were now coming out of the forest and starting to demonstrate it. I really liked it, and but for the sexual relationship stuff I really liked the ambiguity of what was going to happen to Angel, too.

I think, on balance, that I really liked this book. Sinisalo is certainly doing intriguing things, and she does write beautifully.

You can get Troll from Fishpond.

The Slow Regard of Silent Things

In his Foreword, Rothfuss points that that people may not want to read this book. It’s not an ordinary book; there’s no plot. There’s no explanation of who Auri is, who she is anticipating, or even where she is. It’s probably not the first thing by Rothfuss that you want to read.

In his Foreword, Rothfuss points that that people may not want to read this book. It’s not an ordinary book; there’s no plot. There’s no explanation of who Auri is, who she is anticipating, or even where she is. It’s probably not the first thing by Rothfuss that you want to read.

But.

But it is a beautiful object, but it’s a haunting chronicle of six days, but Auri is indeed a bit of the sun.

It’s a beautiful object: I have a hardcover version, and the cover picture is all shadows and moonlight and flowers and Auri’s silhouette. Nate Taylor’s black and white pictures are strewn throughout like the objects that Auri finds, and the text makes way for them so they work together companionably. I’d like to see more books with pictures in them, like this.

It’s not a novel, or a novella (150 pages in this wee format); it’s a chronicle. It outlines Auri’s actions and thoughts for six days. Some days are good, some days are bad. Some days Auri manages to fix rooms and objects so that they are just so and some days she doesn’t have anything to eat. Some days she makes soap. Some days she weeps.

Auri is the only character in this chronicle. In watching her for six days, the reader learns only fragments of her past and nothing of her future. We learn that she is a joyful creature – she grins all the time, and that mostly didn’t get annoying – but she is also deeply broken, and she knows she is broken and feels it keenly. And she knows that the world is broken, too, and she wants desperately to put it to rights, one little bit at a time – finding a place for a bottle, feeding another’s imagination, making soap properly. Anticipating a visitor and fretting about having the right gift.

Auri’s entire life revolves around doing things properly, and making the world right, and not wanting things for herself. I was at points humbled by her, and her willing and joyful self-sacrifice; at times enraged on her behalf, because clearly something has happened to make her so completely self-effacing. At times I was horrified – she has so little to eat – and at time intrigued, as when she contemplates her soap and knows that while it would be perfectly serviceable without perfume and other additions, how joyless to live in a world that was simply <i>enough</i>.

There’s something like 16 pages of making soap. Sounds crazy, I know. Trust me, it works. Or, you know, don’t trust me, because this isn’t your sort of book anyway. That’s fine. I really liked it. (I really liked the first two of Kingkiller Chronicles: The Name of the Wind, then The Wise Man’s Fear.)

This book was provided to me by the publisher at no cost. You can get it from Fishpond.

Jan Morris’ Journeys

Reading a collection of travel essays written in the early 1980s is a surreal experience. So I’ll break this discussion into two parts: by golly I love Morris’ writing, and the essays themselves.

Reading a collection of travel essays written in the early 1980s is a surreal experience. So I’ll break this discussion into two parts: by golly I love Morris’ writing, and the essays themselves.

By golly I love the way Jan Morris writes. She constructs beautiful, evocative sentences. Describing the approach to Wells: “As one descends from the spooky heights of Mendip, haunted by speleologists and Roman snails, it lies there in the lee of the hills infinitely snug and wholesome.” On travelling to China for the first time: “Of course, wherever you are in the world, China stands figuratively there, a dim tremendous presence somewhere across the horizon, sending out its coded messages, exerting its ancient magnetism over the continents.” I’m no writer; I don’t have the ability to assess what makes great prose great. (There’s a great piece of graffiti near my house that says “I know art, but I don’t know what I like.”) I do know that I enjoy Morris’ writing, that I find her descriptions absorbing and sometimes moving, and that some of the books I read would be improved by their authors having read and considered Morris’ style.

Separating the form from the content should not be read as a negative about the content, don’t worry.

The first essay is about Sydney, and as an Australian this was really, really interesting. I felt there were parts that Morris exaggerated, and I was a bit uncomfortable with “Kev,” the white-collar worker standing in for Everyday Aussie, and she pokes a bit of fun at Sydney attitudes and expectations. Now, all of these are standard in a travel essay, sure. But I’ve never read a travel essay by a professional like Morris about somewhere that I kind of know – I don’t actually know Sydney very well, but Morris writes about Sydney as representative of the entire country (to which true Melbournians recoil in horror…). So I enjoyed the essay – she says some very true things, very appropriate things, and of course it’s well written. But it also meant that when I read her other essays, of places I have never been (of every other place she mentions, I’ve only been to Wells), I was aware that a native of those places may well have the same reaction as I did to the Sydney essay. Which made for an intriguing experience: not completely immersed in the narrative or the description, but interrogating her assumptions and elisions and emphases. For this sort of writing, I think my experience was actually enhanced.

This is Morris’ fourth book of essays. None of them have dates attached; the publication details simply explain that most appeared in Rolling Stone, a few in other publications. It came out in 1984 and there’a reference somewhere to 1977, so I presume they all date to that general time; the historian in me really wants dates on each one! There are several essays on parts of the US: my zero interest in Las Vegas succeeded in plummeting even lower, although Santa Fe intrigues; a few on Europe – she’s not a huge fan of Stockholm yet somehow I am now more interested in going, and Cetinje in Yugoslavia (now Montenegro) absolutely fascinates. And the Indian and Chinese essays are probably the most intriguing, and most problematic, in terms of how people and places are viewed.

I love Morris’ work and may well make it an ambition to collect most of what she has written.

Upgrade me now

What do you do when you have a major heart attack and you’re also creator/sustainer of Clarkesworld? You decide to edit an anthology. Natch. (Read an interview with Neil Clarke here.) And you decide to make the theme of that anthology cyborgs, because you are now one yourself. Thus, Upgraded.

Now, before you go all ‘hmm, themed anthology’ side-eye on me, just steady on. In some stories, being a cyborg is the point; in others it is incidental. Sometimes being a cyborg is a good thing, a positive addition, welcomed. Others, it is something to be dreaded, confronted, Dealt With. Sometimes being a cyborg makes you better, and sometimes it seems to make you less. Cyborg-ness ranges from fully integrated and augmented body modifications to one seemingly small addition. Augmentation might be for aesthetics, or employment; for someone else’s sake or your own. It ranges from being socially acceptable to being almost beyond the pale.

Some stories happen tomorrow, here; some of them are way over there, temporally and physically. Sometimes there are aliens. Sometimes there are robots. Sometimes they are in love stories, detective stories, war stories, family stories. Not all the cyborgs are attractive characters. Sometimes they become cyborgs before our very eyes, and sometimes they’ve been cyborg so long it’s just what they are. Sometimes they were actually made that way from the start.

These stories feature men, and women, and sometimes genders are unstated. There are white characters and black characters and a variety of ethnicities. One of the central issues is that of disability, dealing with it and changing it and how those around you react to it. There’s queer and straight and none-of-your-business. Authors are from a variety of backgrounds, too.

So sure, it’s a themed anthology. But this is no Drunk Zombie Raccoons in Upstate New York. This is a vibrant, fun, intriguing and varied set of stories that have a basic concept in common.

The stories. Well, let me say upfront that I was so destroyed by Rachel Swirsky’s “Tender” that I had to put the book down and go to sleep. No more reading for me that night. As for the rest, here’s a sampler: Yoon Ha Lee’s “Always the Harvest” is creepy and disconcerting and sets a really great tone for the anthology – it’s the opening story – by being completely unlike any of the others. Ken Liu’s story is also deeply disconcerting because (very mild spoiler here) it is absolutely not the story you think it is. Alex Dally McFarlane does wonderful things with maps, while Peter Watts taps into the zeitgeist to suggest uncomfortable things about the military. And I have a feeling I know something Greg Egan might have read before writing “Seventh Sight” but I’m not going to mention it here because that would be way too much of a spoiler.

This is a really great anthology, with stories that absolutely stand as marvellous science fiction quite apart from their brethren. You can get it from Fishpond!

Mothership

When I finished reading the first story in Mothership, a little voice in my head said “Was that really the story to start this anthology with? I mean, sure it’s got a black protagonist, but is that enough?”

When I finished reading the first story in Mothership, a little voice in my head said “Was that really the story to start this anthology with? I mean, sure it’s got a black protagonist, but is that enough?”

And then the rest of me took a step back, looked horrified, and said: “Have you learned nothing from Pam Noles’ essay “Shame”? And from the entire Kaleidoscope project? The story has a black protagonist. That’s entirely the point.”

And then I sat, aghast at my own white ignorance, and felt ashamed.

And then I kept reading, because that’s the obvious way to combat such an attitude and is at least part of the point of this project and why I supported its production.

There’s a really wide variety of fiction in this anthology. Some skirt the edge of being ‘speculative’ (Rabih Alameddine’s “The Half-Wall”) while others hurtle over the edge and throw themselves at it. I didn’t click with every story (Greg Tate’s “Angels + Cannibals Unite” really didn’t work for me, and nor did Ran Walker’s “The Voyeur”), but many of them were absolutely breathtaking.

Nisi Shawl’s “Good Boy” – one of the only stories that really qualifies for the ‘mothership’ appellation by being set in space – is a glorious fun romp.

“The Aphotic Ghost”, by Carlos Hernandez, did not go where I was expecting and was utterly absorbing.

SP Somtow’s “The Pavilion of Frozen Women” has a wonderful line in bringing together several quite disparate cultures and tying them together into a fairly creepy thriller.

NK Jemisin does intriguing things with the notion of online communities in “Too many yesterdays, not enough tomorrows.”

“Life-Pod” is Vandana Singh’s haunting reflection on family and identity and connection.

In “Between Islands,” Jaymee Goh suggests how different things might have been for the British in colonising Melaka and surrounds with different technology…

Tenea D Johnson’s “The Taken” is a profound reflection on contemporary issues and problems stemming from the historical transportation of enslaved African to America… I don’t even inhabit the culture that’s dealing with it.

One of the intriguing things about this anthology is that it’s not focussed on African-American fiction, which I had basically expected thanks to the title’s reference to P Funk and Afrofuturism. Instead, there are stories here that draw on Egyptian, Native American, Caribbean (I think? I’m Australian, sorry!!), Japanese and Malaysian (again, I think) traditions and cultures – and those are just the ones that I (think I) could identify. There are definitely others that draw on other Asian cultures (I think there’s an Indonesian one?). The author bios don’t universally identify where the authors are from, so that doesn’t assist in figuring out what might have influenced them… which is not a complaint, by the way, because so what? (in the most prosaic ‘fiction is fiction’ sense). So it’s a really broad understanding of what falls into “Tales from Afrofuturism and beyond” – much more inclusive therefore than, for example, many anthologies of the last few years, let alone decades.

This is an good anthology, period. That it’s exploring and accomplishing a particular political aim is icing on the cake. You can get it from Fishpond!

The Bitterwood Bible

Sourdough and Other Stories by Angela Slatter has been on my radar for ages, but somehow I’ve just never got around to reading it. For a while I didn’t realise it was available as an ebook – and Tartarus Press does lovely hard copies, but they’re a leedle expensive for a book you’re taking a chance on. And I also wasn’t sure that these stories were ones that I would really connect with. I mean, yes, I loved “Brisneyland by Night” in Sprawl, and a few others Slatter has written – especially with Lisa L Hannett – and Midnight and Moonshine made me cry with its beauty, but… I just wasn’t sure. And then I found out that Slatter had a set of ‘prequel’ type stories coming out, so I thought I should read those first.

Halfway through reading The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings, I finally bought myself Sourdough because there is no way I can now not read that collection. Because I am absolutely an Angela Slatter convert.

Halfway through reading The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings, I finally bought myself Sourdough because there is no way I can now not read that collection. Because I am absolutely an Angela Slatter convert.

The stories collected here are not quite a mosaic in the same way that Midnight and Moonshine are. There, each story was clearly connected – most often by family, which made it seem a generational saga. Here, while there are a couple of stories that feature the same protagonist, a few more with recurring cameos, and most set in the same place or with the same background characters, it’s more like a series of stories set in a couple of distinct suburbs or small towns. Of course you’re going to get the same bars, or neighbourhood characters, or landmarks mentioned; that just makes sense. But the narratives themselves aren’t necessarily connected… although sometimes they are. And these locales that Slatter has invented are very believable. They’re well-realised, and they’re familiar in that fairy-tale sort of way. Because these are indeed a sort of fairy tale. There’s not a whole lot of magic; what there is is generally a quiet, dare I say domestic without it being in the slightest derogatory, magic; no flashiness or gaudiness here, no winning of wars. That would draw too much attention, and drawing attention in these stories is generally A Bad Thing. The women – and the protagonists are almost all women – mostly want to be left alone, to get on with their lives. Sometimes they’re forced to interact with the world, or with other people, that they’d rather not; because they need to achieve some specific goal, or because they’re being manipulated, or they otherwise have no choice. But you certainly get the feeling that most of them would just prefer never to be in the limelight, not to be a household name… not to stand out.

There are scribes and poisoners, seamstresses and pirates, teachers and coffin-makers and servants. They are mothers and daughters and child-free and orphan, young and old and neither; rural and urban, rich and poor. They have varying degrees of agency and control, varying chances of living after and of living happily ever after.

This is a wonderful collection of stories. They can and should be read and enjoyed separately; they can and should be read and enjoyed together, making a whole even greater than its parts. Oh, and Kathleen Jennings’ lovely little illustrations throughout are a delightful addition; I imagine they’re even more impressive in print, but electronically they’re still fine.

This review is part of the Australian Women’s Writers 2014 challenge.

1968: a biography

This book came out a decade ago. I think I’ve owned it for that same length of time – I seem to recall getting it as a freebie at some readers’ night at a bookshop. I’d adored everything else by Kurlansky that I’d read, so it seemed like a good deal at the time. And then it just… got lost in the pile of books that I own and haven’t got around to reading. As happens all too often. Plus, I overlooked it because after all, 1968 is really quite recent, yeh? And modern history… well, it’s just politics. And there’s more interesting stuff to read than politics.

This book came out a decade ago. I think I’ve owned it for that same length of time – I seem to recall getting it as a freebie at some readers’ night at a bookshop. I’d adored everything else by Kurlansky that I’d read, so it seemed like a good deal at the time. And then it just… got lost in the pile of books that I own and haven’t got around to reading. As happens all too often. Plus, I overlooked it because after all, 1968 is really quite recent, yeh? And modern history… well, it’s just politics. And there’s more interesting stuff to read than politics.

I’m not sure what made me pick it up last week. Possibly something I’d been talking about with someone, or I wanted to check something. Who knows; doesn’t matter. What matters is I read the introduction and I was hooked. Kurlansky talks about four significant factors that made 1968 stand out: the example of the civil rights movement in the US speaking to a generation that felt alienated and who despised a war being waged by a massive nation against a small one, and all of it occurring at a time when television was becoming a potent force. It’s not a unique year – I’m sure you could write this sort of insightful ‘biography’ for most years, of the twentieth century especially. But it really is a significant year.

(A little quibble about the cover: the Rolling Stones aren’t mentioned, so why put Mick with either Tommie Smith or John Carlos, who used the Black Power salute at the Mexico Games, and a soldier in Vietnam, and a rocket? It doesn’t really make sense. If they wanted to symbolise the student movement, then surely Abbie Hoffmann or a SDCC poster or similar would have done the trick. It irked me. )

From the point of view of a historian, Kurlansky is quite open about the impossibility of his being completely objective, and in fact rejects the idea of any historian doing so. He was born in 1948 and hence experienced a little bit of what he’s writing about, especially the anti-Vietnam stuff. This comes through in how he writes, but how much that’s a problem is going to depend on how hungry you are for that impossibly elusive objectivity – and how hard you find it to sift the presentation of information to find whatever you think is ‘true’. I think that the medium for conveying the message is worth it, and you just read with that in mind.

And this book is worth reading both for the style – which is intensely readable – and for the content. Kurlansky eschews too many footnotes (and in fact makes that endnotes, and without numbers in the text), so it reads less like a formal history and more as an engaging narrative. Yes the historian in me occasionally frowned at some of the things he says without appearing to back it up. That’s what you get for more conversational-style history… and actually that suggests what this book is like: it felt more like the book of the series. I can easily imagine each of the chapters here being turned into an episode of television.

The absorbing nature of the narrative is aided by the astonishing story that’s being told. Bare bones: Martin Luther King Jr and Robert F Kennedy are both killed in this year; there are student riots/protests/movements all over the US and the birth/growth of significant student movements, as well as in France, Germany, Mexico, Poland and Czechoslovakia, sometimes accompanied by workers’ movements; the Olympic Games in Mexico; attempt at revolution in Czechoslovakia that’s put down by Soviet tanks; civil war in Nigeria; unrest in Israel; the Tet Offensive in Vietnam; Nixon winning the US election; Apollo 8; race issues, gender issues, political issues… . Yeh. It was a big year.

Kurlansky does a wonderful job of putting actions in different places in perspective – connecting them to one another. This is particularly true of the discussion around the student movement, which is really the heart of the book. And there’s something to be warned about: although there is quite a good discussion (IMO) of the Polish and Czech experience, especially, this is still at heart an American book. The Nigeria/Biafra ‘conflict’ is dealt with seriously and soberly, but it doesn’t get nearly as much air time as the attempts at student sit-ins around American universities. Is that a problem? Depends on what you’re wanting out of the book. And it depends on what you think actually made more of an impact around the world at the time, and since then. The by-line is “The year that rocked the world.” Did American students flagrantly defying authorities, and students being beaten by police, ‘rock the world’ more than a million people dying in Biafra? … unfortunately, possibly yes, for several reasons – not least of which is the one that Kurlansky himself spends quite some time discussing: television. There were cameras rolling when students got beaten in the streets of Chicago and New York. Not so much in Nigeria. Plus, the reality is that America had and continues to have more of an impact on world attitudes and trends that Nigeria does – for good or ill, in terms of ascertaining impact it doesn’t matter. My point is more that if you want a book that balances every country’s experience equally, this is not for you. It’s more than the history of one nation but less than a complete history of the world. So check your expectations first.

This is a really fabulous book for bringing out the important issues and the people of this one year. He sets the events and the people into context – casually dropping in Yasir Arafat and Bill Clinton, among others, for future connections, as well as giving background on Martin Luther King and the development of Palestinian identity and the Nigerian conflict and issues in Czechoslovakia. It’s not quite a history of the entire decade but it’s more than just a history of a year.

I love that this book ends with optimism. 1968 itself is such a torrid confusion of hope and despair that going from “racism, poverty, the wars in Vietnam, the Middle East, and Biafra” to the picture of our little blue and white and green marble, as seen from Apollo 8 going around the moon, seems peculiarly appropriate. And then to conclude with Dante – “Through a round aperture I saw appear / Some of the beautiful things that Heaven bears, / Where we came forth, and once more saw the stars.”

This book can be found on Fishpond.

Landline: review

This book was provided to me by the publisher.

This book was provided to me by the publisher.

I’ve never read anything else by Rainbow Rowell, but a lot of the Goodreads reviews talk about her style being really easy – and it is. I started reading this late one afternoon and I’d read the first 100 pages before I realised what had happened. The story is well-paced; officially it takes less than a week, although there are serious flashbacks that kinda make that a lie. The prose flows – lots of familiar-sounding dialogue, enough detail to sketch in believable places and people. I’m not great at explaining how prose works. All I know is that this was delightful to read, and partly that was the words themselves.

The premise: Georgie has the chance at a dream job – but she’ll have to work over Christmas. Husband and kids go off on their family holiday without her. Georgie discovers that the old landline at her mum’s house somehow allows her talk to her husband – but him from the past. The novel is then filled with the minutiae of daily life: work and memories and family relationships and that worrying and gnawing at problems that gets so familiar when you’re old and have lots of worrying to do.

The best thing about this story is that it’s about a woman thinking about, and worrying about, her marriage. That sounds very self-indulgent and maybe a bit dull or stupid, but bear with me. It’s refreshing to read about a woman confronting problems like this and not taking all the blame, not taking a convenient way out, and not having things magically solved. (Maybe there are lots of books like this – in fact I’m sure there are – but they’re not on my radar.) Yes, there were a few points where I got a little uncomfortable about what might almost be being suggested about her (‘letting herself go’, etc), but for me at least they never quite got to the really problematic point; they were redeemed by some thought or action that pulled it back, didn’t make her the villain for not having time to buy new bras, and so on. And I liked that the focus was on the bit after the happily-ever-after – the bit after marriage, and after kids, and things aren’t entirely wonderful but they’re also not entirely horrid, they’re just… life. But they can still be better, and yes life and marriage require work and that’s ok.

Georgie was pretty easy to identify with, and all the surrounding characters were too. At times I wondered if Rowell was trying too hard to be ‘inclusive’ – but then I realised that just maybe I was overthinking it, that actually there wasn’t a huge amount of diversity (although to be fair the cast isn’t that big), and that none of the ‘minority’ characters were such just to make a statement. (See how my brain gets me caught up in tangles?) Also, the pugs are hilarious.

Self interrogation:

I was going to start this review by saying “this isn’t the sort of book I normally read.” Which is basically true, but why start with that line? And I started thinking about the answer to that question. And then I thought about starting this review with this self interrogation… and I realised that that was still front-and-centring the issue, rather than the novel. It’s one worth talking about but it’s entirely too self-indulgent to make it the first bit. So, here it is, at the end.

This is not the sort of book I normally read. Because it is, first and foremost, a romance. And I don’t think of myself as someone who reads romance, even though actually I love ‘good’ romance in my novels and movies – by which I mean it’s realistic but/and sweet but not saccharine, and – most especially, in my head – not the focus of the story. So why was I so keen to defend myself? Because despite all the time I spend thinking about why reading SF isn’t a bad thing to do, I still automatically feel like I have to barricade myself away from that genre – the female one, the one that everyone else bashes when they’re not bashing romance – even though I am well, well aware – in my head – that oh my goodness there are so many things wrong in thinking/acting like that. And the other thing is that this is absolutely SF. If we’re happy to accept John Chu’s “The Water that Falls on you from Nowhere” as SF – and heck, we should be – then so is this. That short story is all about a romantic relationship and how it works out with the family; the SFnal element is water that, literally, falls on you from nowhere. It’s never explained. So this, a story that’s about a romantic relationship and family, where the main character has access to a phone that allows to talk to someone 15 years ago? This is absolutely SF. Was I more embarrassed because this was written by a woman, and therefore more clearly can be classified as a romance? Because it’s a novel rather than a short story from an obviously SF venue? Who knows. At any rate, I’m not embarrassed by having read it, because it’s one of the easiest – pleasant, fast, cosy – books I’ve read in ages.

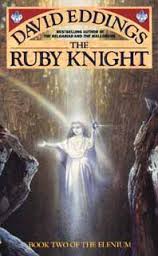

The Ruby Knight

EDDINGS RE-READ: The Ruby Knight, BOOK TWO OF THE ELENIUM

EDDINGS RE-READ: The Ruby Knight, BOOK TWO OF THE ELENIUM

Because we just don’t have enough to do, Tehani, Joanne and I have decided to re-read The Elenium and The Tamuli trilogies by David (and Leigh) Eddings, and – partly to justify that, partly because it’s fun to compare notes – we’re blogging a conversation about each book. We respond to each other in the post itself, but you can find Tehani’s post over here and Jo’s post here if you’d like to read the conversation going on in the comments. Also, there are spoilers!

ALEX:

Sparhawk starts this book a) immediately after the end of the first one, and b) wanting someone to jump him, so that he can get all violent on some unsuspecting footpad. I don’t think I was really paying attention to that sort of thing when I was a teen. He’s actually not a very nice man a lot of the time, and that makes me sad.

JO:

It is a bit sad isn’t it 😦 Sparhawk’s most common reaction seems to be violence, and the narrative and tone celebrates that part of him.

TEHANI:

Alex, you say “not a very nice man” but I never read it that way (and still don’t, I guess!) – he’s a product of his culture and his time. They seem to quite happily wreak havoc on people at the drop of a hat, and he IS a knight, trained to battle!

ALEX:

OK, maybe I don’t have to be quite so sad about him – that he’s a product of his time – but still his active desire for violence does act, for me now, against my lionising of him as a teenager. He is flawed, and I’m troubled because Jo is exactly right – the narrative celebrates him and his anger/violent tendencies.

TEHANI:

You’re both completely right. I still choose to read it in the context of the book, AND STICK MY HEAD IN THE SAND. Damn. That’s the problem with rereading with a few more brains behind us, isn’t it?!

ALEX:

Something we didn’t note in our review of The Diamond Throne is that the book is prefaced by a short excerpt from a ‘history’. This is a really neat way of building up back story and developing the world without having to info-dump – although of course the Eddings pair don’t really have an issue with info-dumps; after all, why else assign a novice knight to teach a young thief history? Anyway, I still like it, and it does show that there has been a fair bit of thought put into the world, even if much of it simplistic.

JO:

Yeah I enjoy these histories too. Good way to set the scene, highlight anything that’s going to be important for the book (like Lake Randera) and do a quick recap. They definitely like an info-dump, but at least the Eddings do it with style and humour!

TEHANI:

I reckon there’s reams of world-building behind these books, especially if the work that we see in The Rivan Codex (for the Belgariad/Mallorean world) is any context!

JO:

I enjoyed this book a lot more than I expected. I remembered The Ruby Knight as a very ‘middle book’, just basically a long build up to finding Bhelliom and saving Ehlana. But on the reread it was a lot more engaging than that. Maybe it’s because Eddings has the space here to really get into the characters, and I love these characters so much that I enjoyed that to no end.

TEHANI:

It really does boggle me that even though I’ve read this several times, I still don’t get bored of this long questy-ride-alonging. It really IS a middle book, and nothing terribly much happens, but it’s still a really enjoyable read! Bizarre. Is it nostalgia that makes it so, or some quality about the book that means I don’t chuck it across the room like I would most other “middle books” that really just march in place?

ALEX:

I found this one a bit more boring than I remembered – it really is just them wandering around. I totally still enjoyed the character development, and it is banter-ific, but on this re-read I got a bit impatient with the lack of actual plot movement.

JO:

They’re also very good at throwing everything in Sparhawk’s way. I mean, this is basically a quest book. We even have a ‘fellowship’ don’t we – Sephrenia mentions how important it is to have a certain number of people on the quest, it’s all about symmetry. But from the outset, everything that can go wrong does, and all of this does a great job of increasing the tension. Not only that, but characters we meet in the beginning and/or middle come back towards the end, which makes these side-quests feel a little less side-questy. By the time Sparhawk and Co. get roped into Wargun’s army I just wanted to scream because they were so close and it is so not fair! But I do love it when characters get put through the wringer like that. Nothing’s easy.

TEHANI:

Masochist! But I’m right there with you – wouldn’t be any fun if things just went to plan, right?

ALEX:

omg when I got to that and remembered that they were being co-opted I think I might actually have groaned out loud. GET ON WITH IT.

TEHANI:

I like that there’s a few points in this book that smack back at the classism – Wat and his fellows teach Sparhawk a thing or two: “Not meanin’ no offence, yer worship, but you gentle-folk think that us commoners don’ know nothin’, but when y’ stack us all together, there’s not very much in this world we don’t know.”

Ulath backs this up some chapters later: “Sometimes I think this whole nobility business is a farce anyway. Men are men – titled or not. I don’t think God cares, so why should we?”

“You’re going to stir up a revolution talking like that, Ulath.”

“Maybe it’s time for one.”

ALEX:

Tehani, you beat me to it – I LOVE that bit; I metaphorically punched the air.

JO:

Go Ulath! 🙂

TEHANI:

Unfortunately, there is also some nasty gender stuff – it doesn’t stem from our heroes, but isn’t challenged by them, and is somewhat supported by them to an extent (Kurik emphasises the nasty noble’s words by drawing his sword in this exchange):

“Mother will punish you.”

The noble’s laugh was chilling. “Your mother has begun to tire me, Jaken,” he said. “She’s self-indulgent, shrewish and more than a little stupid. She’s turned you into something I’d rather not look at. Besides, she’s not very attractive any more. I think I’ll send her to a nunnery for the rest of her life. The prayer and fasting may bring her closer to heaven, and the amendment of her spirit is my duty as a loving husband, wouldn’t you say?”

(more follows on p. 217 – of my copy…)

ALEX:

urgh. Hate that.

JO:

And it’s ok that he feels this way because it was an ‘arranged marriage’. Poor bloke, getting stuck in an arranged marriage like that. *flat stare* There are a lot of comments in these books about women being obsessed with marriage and men ‘escaping’.

ALEX:

And there’s other uncomfortable gender moments, too, like the serving girls in the tavern often being blonde, busty, and none too bright… *sigh* And then there’s Kring, who asks whether it’s ok to loot, commit arson, and/or rape when they partake in war with the Church Knights.

TEHANI:

Oh, so many uncomfortable moments…

JO:

Yeah I’d totally forgotten that about Kring. I was so excited to see him, because I always liked him, but that took the wind out of my sails a bit.

TEHANI:

But Kring kind of changes, I think (though later on) and that element is quite lost later. However, it does NOT do well to realise which culture the Peloi are intended to represent. Oh, the casual racism…

ALEX:

On the topic of racism – every time Sephrenia rolls her eyes and says “Elenes,” I can’t help but think of the bit in The Mummy where Jonathan says “Americans” in that insulting tone of voice (which I can’t find on YouTube, darn it).

TEHANI:

I think Sephrenia is quite within her rights saying it in that EXACT tone of voice!

ALEX:

Also, Ghwerig being ‘misshapen’ isn’t quite suggested as the reason for his being evil, but it’s pretty close – and keeps cropping up throughout the series. I can’t imagine how that makes a non-able-bodied reader feel, given it makes even me gnash my teeth.

TEHANI:

You know, I never actually read it that way – it mustn’t be quite as overt as some of the other uncomfortable things. But of course, now you’ve pointed it out, yes, I completely see it.

JO:

Oh hey I never really noticed that either! But now that you mention it, I can’t unsee it. Which says a lot. Why do I see all the gender stuff immediately, but this passed me by? Of course there’s a long literary tradition of physical deformities = spiritual ones. That’s no excuse. I must be more aware in my reading.

TEHANI:

Kurik’s acknowledgment of Talen (p. 392) made me cry as much as it did Talen!

ALEX:

You softy. I didn’t cry in THAT bit…

JO:

Oh no, the bit that always made me cry is still to come…

ALEX:

Mine too.

Apropos of nothing, did either of you find it a bit odd that Kurik checks on Sparhawk in the middle of the night?? I bet there’s fanfic out there…

TEHANI:

There’s fanfic out there for EVERYTHING! I didn’t think it odd, though I did love the naked man-hug in the early pages of the first book! (go on, go check, I’ll wait…) 🙂

JO:

I am NOT going to go looking for fan fic. I am NOT…

ALEX:

Oh, I don’t need to check, Tehani, I remember 😀

Also, do you remember whether you suspected Flute of being actually divine before the great revelation at the end of this story? I’m not sure! I hope I did…

TEHANI:

Well, I read these completely backwards (Tamuli before Elenium), so I was spoiled for that already I’m afraid!

JO:

Tehani that breaks my brain.

I had suspicions about Flute from very early on. I remember being very impressed with myself at the time. I reread it now and think how could you not? They do kinda hit you over the head with it :p

TEHANI:

I think by now we’ve read WAY too much in the field to be surprised by something like that – but a newish reader to the genre? Maybe they wouldn’t pick it!

Well, being the middle book of the trilogy, there isn’t really much by way of plot to chat about, I guess, so shall we move along? Perhaps faster than the plot of the book itself… 🙂

JO:

We should talk about plot shouldn’t we 🙂

Sooo… As usual the book opens up with Sparhawk travelling through Cimmura at night in the fog. Notice how often that happens in these books?

TEHANI:

Yes, you’re right! It’s a trend in the books, for sure.

JO:

I quite like the repetition. He’s got both rings, and now he knows he needs Bhelliom to cure Ehlana and it’s time for the sapphire rose to be found again anyway. The fellowship head off on their quest for the magic jewel and have adventures along the way, including being stuck in the middle of a siege, dealing with Count Ghasek’s possessed sister, raising the dead and finally fighting the Seeker who has been chasing them all this time.

Eventually they make it to Ghwerig’s cave – after the introduction of Milord Stragen, another favourite character – fight and defeat the troll. Flute is revealed as the child-Goddess Aphrael, and gives Bhelliom over to Sparhawk.

Was that the kind of thing you had in mind? 😉

TEHANI:

This is why YOU’RE the writer…! Nicely summed up indeed. The Count Ghasek storyline was a bit of a tough one. On one hand, Ghasek seemed like a nice enough chap. On the other, the motives behind his sister’s madness, well, not great to examine that too closely, I think.

JO:

Although I did appreciate the throwback to book one – Eddings could have introduced any old character here, but Bellina is the woman Sparhawk and Sephrenia witnessed going into that evil Zemoch house.

TEHANI:

Well seeded indeed…

ALEX:

GET ON WITH THE STORY, EDDINGS PEOPLE!

The Diamond Throne

EDDINGS RE-READ: The Diamond Throne, BOOK ONE OF THE ELENIUM

EDDINGS RE-READ: The Diamond Throne, BOOK ONE OF THE ELENIUM

Because we just don’t have enough to do, Tehani, Joanne and I have decided to re-read The Elenium and The Tamuli trilogies by David (and Leigh) Eddings, and – partly to justify that, partly because it’s fun to compare notes – we’re blogging a conversation about each book. We respond to each other in the post itself, but you can find Tehani’s post over here and Jo’s post here if you’d like to read the conversation going on in the comments. Also, there are spoilers!

TEHANI:

I was feeling a little book-weary yesterday so thought I might as well start my reading for this conversational review series, given it’s usually a soothing experience. Within a single PAGE, I was reaching for Twitter, because SO MUCH of the book cried out to be tweeted! Great one-liners, the introduction of favourite characters, and, sadly, some of the not so awesome bits as well. I was having a grand time pulling out 140 character lines (#EddingsReread if you’re interested), but the response from the ether was amazing! So many people hold these books firmly in their reading history, and it was just lovely to hear their instant nostalgia.

ALEX:

And I read those tweets and everything was SO FAMILIAR that I immediately started reading as well. And finished a day later.

JO:

Ok. A) You people read too quickly! B) Tehani those tweets were enough to start me feeling all nostalgic. I was in the middle of cooking dinner and had to put everything down, run upstairs and dig the books out of their box hidden in the back of the wardrobe.

TEHANI:

I am not at all repentant! 🙂 Also, did you both find this a super easy read? Is it the style, or just that I’ve read it several times before? It really was like sinking into a warm fluffy hug, hitting the pages of this book again. I actually can’t remember the last time I read it, but it’s got to be over a decade, yet I felt instantly at home again. Eddings was one of the authors who caused my addiction to the genre, and even in the very first chapters, it’s easy to see why. The light and breezy writing style is instantly accessible, and the way we’re thrown straight into the action, with our hero Sparhawk leading us through, makes the book start with a bang.

ALEX:

Reading that first page was a little bit like going back to my high school, many years after graduating. It just felt so familiar, and comfortable. And like high school, I know it’s not without problems – but it’s still somewhere that has a lot of ME wrapped up in it. I also don’t remember when I last read these, but it’s not for aaaaages… And yes, super easy to read. TOO easy! ;D

JO:

Oh yes, absolutely. As soon as I started reading it all came back to me. I remembered the moment I found The Diamond Throne in the library, and the first chapter and intro of Sparhawk hooked me instantly. While I think as a teenager I identified the most with Polgara from the Belgariad (I wanted to BE her) I have always loved Sparhawk.

ALEX:

Polgara is still one of my absolute favourite characters! Sparhawk is too, though – one of the great characters for me in my early teen years. I adored that he was older, and cynical, and world-weary. When I was 14 I thought I was all of those things…now that I am 34 I still absolutely empathise! This story also shows that his cynicism is cut with a very large streak of sappiness, which I think serves to make him just a bit more relatable. His love for Sephrenia, his respect for Vanion and Dolmant and Kurik – he’s actually a fairly well-rounded character, as these things go. His habit of calling people ‘friend’ and ‘neighbour’ is why I call everyone ‘mate’ to this day. True story. I also adore the relationship he has with Faran, that ugly roan brute; I love Faran unconditionally.

TEHANI:

He is so pragmatic, completely prepared for violence at all times, and yet from the very early pages where he gives the street girl some coins and calls her “little sister”, we see he’s an absolute marshmallow inside. I’m with you Alex, I adore him.

JO:

I have an admission to make. I still love him, but Sparhawk’s making me a little uncomfortable in this reread. For all his neighbours and his giving money to the scrawny whore, I’m starting to feel like he’s a bit of a bully. He gets what he wants because he can and does threaten violence if he doesn’t get it…and it feels like Eddings thinks this is ok because he’s Sparhawk. He’s a Pandion (not only a Pandion but the best of them, as we are repeatedly reminded) and the people he threatens are ‘evil’ anyway so no harm done… I dunno, it’s just made me feel a bit squeamish this time round.

TEHANI:

That’s a really good point. I’ve had a similar discussion with my Doctor Who reviewing buddies Tansy and David about David Tennant’s Doctor – he does and says some pretty awful things, but we accept it generally without question a) because he’s the Doctor, but more importantly b) because David Tennant plays him so charismatically. Sparhawk has the same sort of issues – we know (or are given by the narrative to believe) that he’s on the side of right, and that he is the Champion, therefore we accept his behaviour because it’s presented as being for the right reasons.

ALEX:

*sigh* you are of course both correct – Sparhawk’s use of “might is right” is totally accepted by the novel because he is so awesome. And if that’s not an abuse of power, right there, then nothing is.

On a more positive note, I think I like all of the other characters, too. Sephrenia is delightful although definitely not rounded out enough here…and I do have a problem with her “we Styrics are so simple and you Elenes are so complex” thing. I want to believe that she’s just serving back to the Elenes what they believe about themselves, so that she can manipulate them, but I’m not sure if that’s knowledge of the rest of the series or wishful thinking (more on that below). Talen is already totally amusing and reminds me a lot of Silk, from the Belgariad, which is unsurprising. The Merry Men really are dreamy; Ulath and his blonde plaits will always be my favourite, because who doesn’t love the quiet cryptic type?

TEHANI:

And I adore Kalten, because he’s always needling Sparhawk yet they clearly love each other. Talen was a definite favourite from early on too, and Kurik is marvellous – a definite father figure, or maybe more an uncle…

ALEX:

The classism and the racism…ouch. The Rendors are meant to be Arab analogues, right? Because everyone knows that living in the heat makes your brain go soft. OUCH. Also, why have I always thought the Styrics were analogues for Jews? Is it just that the Elenes burning their villages is frighteningly similar to pogroms in Christian Europe in the Middle Ages? (But of course there’s no religious similarity at all, and the only ‘real’ similarity is the refusal of pork.)

JO: I always thought that about the Styrics too.

TEHANI:

Oh yes, that was the first thing I picked up on in terms of the negative stereotypes – completely over my head when I read these in my late teens, front and centre now. I actually wrote a uni paper on representations of reality in Eddings and Feist, but I’ve sure learned a lot since then! I could easily IDENTIFY the real world correlations, but did I notice the negative aspects of this? No I did NOT. *sigh* Bad past me, bad!

This time around, the classism was just as interesting too – I think I was so indoctrinated into the usual process of high fantasy in my 20s that this would never have even occurred to me to see. This time though, Sephrenia’s derision about the intelligence “common” Elenes and Styrics is, ugh, just awful. And when it’s other races as WELL as commoners, well, that’s terrible.

ALEX:

The class aspect is ugly as all get out. When they’re in the council chamber confronting Vanion, Dolmant – the lovely, gentle Dolmant – says why believe an untitled merchant (his words!) and a runaway serf over and above the honorable Preceptor (code: titled)? Now we know that those are both lying, but that’s beside the point. I dunno, Dolmant, maybe because truth and honesty aren’t actually the privileges of the wealthy and titled?

JO:

Oh goodness yes. I have to admit this is something that passed me by the first time I read these. Maybe because in the world Eddings writes it does feel so natural. Which is disturbing.

TEHANI:

It really is, isn’t it! And once you see, you can’t unsee…

ALEX:

This is one of the first real instances I remember of the Crystal Dragon Jesus trope – taking what can be broadly recognised as a version of the medieval Catholic Church and transporting it to a secondary fantasy world.

TEHANI:

I’ve not heard of the “Crystal Dragon Jesus trope” – please elaborate?

JO:

Neither have I!

ALEX:

Instead of creating your own religious system for your magical fantasy world, you take the broad brush strokes of (usually) the medieval Catholic Church – because hey, everyone knows that medieval stuff is bad, plus Catholics are easy to laugh at, right? It generally involves a monotheistic religion with a convoluted hierarchy, seemingly-pious churchmen (and only men) who are meant to be celibate but often aren’t, because that also makes them easier to turn into evil characters. The only thing that the Eddings missed is the saviour/messiah/ someone who sacrificed themselves bit, of the religion. It irks me because it is so lazy.

JO:

I did not know there was a term for that 🙂

ALEX:

Tehani, you said there was a Lord of the Rings reference early on – did you mean Ghwerig the Troll-Dwarf being like both Sauron and Gollum, with the whole rings thing? (Also, how did Ghwerig ‘casually’ smash a diamond?) There’s also a Hamlet reference, at the end, when Sparhawk comes across Annias praying in the chapel and chooses not to kill him.

TEHANI:

Yes, exactly! I missed the Hamlet reference, and I think there were a couple of others in there!

I could hand-wave the diamond smashing – I figured if he was working under the influence of the gods, he could pretty much do anything!

JO:

You know, there’s a lot of repetition in this book. It almost feels like any time anything happens, it has to be reported back to the group in the next scene, and discussed. Same goes for any time they meet a new character, we have a recap of events up until this point. All done with amusing dialogue, of course. But still!

TEHANI:

You’re right, but it’s so breezily written I hardly notice it! I do quite like the way travelling actually takes a significant amount of time, even when that slows down the action.

ALEX:

Thanks to your tweets, Tehani, I noticed every single time the word ‘peculiar’ was used.

JO:

By the end there I was getting a little sick of “I’m (terribly) disappointed in you, ___.” Or something similar. I noticed it a couple of times then couldn’t unsee it!

TEHANI:

Yes, Eddings has several “tics” of writing that once you notice them, you ALWAYS see them! “Flat stares” are my favourite 🙂

JO:

Particularly when they come from Faran. I love that horse and his flat stares.

TEHANI:

That horse is practically human.

ALEX:

That horse and his prancing make me happy.

JO:

I’m having a strange and conflicted reaction to the female characters in these books. On the one hand, they are such wonderful strong people. Sephrenia is powerful, but that’s almost not what makes her strong – rather her pacifism compared to the bloodthirsty knights around her, and her determination to do her duty to her goddess. And her relationship with Vanion. Ehlana’s still encased in diamond at this point, but the effect she had on Sparhawk pretty much says it all! Even Arissa has her own desires and knows her own mind. But…but… I dunno, something feels off to me. Maybe because there are few of them? Maybe Lillias’ rather large hissy fit soured it all for me. I just don’t know. Would love your reactions.

TEHANI:

I actually thought the Lillias thing was reasonably well handled – it was made pretty clear it was a cultural “norm” rather than her personal feelings, which made it okay for me, I guess. The female characters are interesting though; I wonder if it’s because they are constantly stamping their feet at the men and pretending to be less powerful than they are to get their own way that’s the problem? Possibly I’m getting ahead of myself though – this is only the first book!

ALEX:

I loved Lillias’ melodramatic turn – and that Sparhawk played to it for her sake. I am conflicted about Sephrenia: are the knights looking after her because they love her, or because they see her as weak? Or is that an “and” situation? I don’t like Arissa but I admire her strength. For me, I think it’s that this is such a boys world the women feel a bit out of place. The other female character of course is Flute, and she’s quite funny, but one thing I wanted to point out: she ‘somehow’ escapes the convent where they leave her, and meets the crew further on…and no one goes back to tell the convent she’s ok?! Seriously??

TEHANI:

Don’t look too hard Alex, there’s all SORTS of little nitpicks like that! I think we’re almost ready to move on to the next book. I don’t suppose it really matters that we’ve not talked about the plot, right? It’s your basic high fantasy quest, with lashings of barriers thrown into our hero’s journey, a cast of thousands (seriously, it gets quite large in the end…) and lots fun dialogue that means you completely don’t notice that sometimes nothing really happens for several pages *cough chapters cough*.

ALEX:

Things happen! Characters develop! Banter is committed! 😀

JO:

Yeah, what more could you possibly want? Lots of riding horses to get to places. Things go wrong for our heroes all the time. I do think Eddings is good at that in particular. Just when you think they might finally achieve something, *bam* something goes wrong. Usually involving Martel. And yes, lots of banter. Banter is awesome.

TEHANI:

Hey, have you two seen this? http://42geekstreet.com/fantasy-casting-agency-the-diamond-throne-the-elenium/

ALEX:

omg. How awesome. One big nitpick: they CANNOT make David Wenham Martel! Nononononono. No. Kalten maybe?

JO:

LOL ‘who could play Sparhawk in a movie’ is my husband’s favourite pastime. It drives me nuts.

Also, Gerard Butler? Gerard Butler? That’s it, I quit the internet. *walks away from the internet*

TEHANI:

What’s WRONG with Gerard Butler! *wanders off whistling* See you both back here for the next exciting instalment of our reread!